Joel Paula is a Research Director at FCLTGlobal. This post is based on a FCLTGlobal memorandum by Mr. Paula, Jess Gaspar, Matt Leatherman, and Sarah Williamson. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Paying for Long-Term Performance (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

To be successful, companies need to attract and reward leaders who create value over the long term, but executive remuneration often focuses on short- term targets. Shareholders and their advisors similarly focus on short-term returns as a primary metric in the evaluation of pay plans. Replacing these short term-oriented approaches with direct long-term stock ownership by executives is a better solution.

It’s no surprise that executive remuneration stands out as one of the most visible and closely examined aspects of a publicly listed company’s corporate governance program.

Companies, and their corporate boards who set remuneration policy, are facing increasing pressure on executive pay amid rising shareholder scrutiny of pay plan proposals. Last year’s proxy season in the United States saw a record number of say-on-pay failures. Yet say-on-pay voting at publicly listed companies has arguably had the opposite of its intended effect, driving up executive compensation and showing little relationship to long-term shareholder interests.

Total shareholder return is the most common metric that shareholders employ to align interests, but it is often short term-oriented. By tying executive pay to stock prices over short periods of time, companies and investors are actually putting their long-term interests at risk.

The most effective remuneration structures are matched to a company’s objectives, strategy, and management. The simplest solution is direct stock ownership by executives, with long-term holding periods. This arrangement is similar to private equity-backed companies’ structures, where the focus is on executive wealth creation over time. This report offers practical tools to aid corporate boards in designing executive remuneration, calibrating long-term equity awards, and effectively communicating remuneration policies to shareholders. These actions include the following:

- Replacing approaches that are counterproductive in the long term, and focusing on rapidly building executive share ownership through restricted stock and share retention policies

- Applying alternative indicators to gauge compensation structure and incentives

- Streamlining corporate disclosure of pay practices, emphasizing the decision-making narrative

Investors require simplified approaches to say-on-pay voting that are aligned with long-term remuneration design. We propose a framework that focuses on five key elements: holding period, quality, targets, instruments, and progress, each of which is broken down into key elements that investors can use to update their proxy voting policies. This is a critical step to take: by clearly stating in writing what criteria are likely to lead to a no or yes vote, investors can lean into a set of principles that drive proxy voting and contribute to positive change at portfolio companies.

We expect that over time, digital technologies like artificial intelligence will revolutionize the process of gathering remuneration data for proxy voting. Tools like pay duration and wealth sensitivity, which we present in this report, have complex data needs. But they need not be so complicated, given currently available technologies. The proxy agencies, who hold significant sway in proxy voting outcomes, could embrace these technologies to help broaden the tools available to companies and investors alike.

THE CEO SHAREHOLDER: INCENTIVIZING LONG-TERM PERFORMANCE

The frustrations of both companies and investors with say-on-pay voting

Executive remuneration design is a primary decision for all companies. Structuring pay effectively is critical for attracting, retaining, and motivating a CEO, and it also affects the wider organization. Performance targets set with senior leadership trickle down through the firm and become an imperative for all employees. The design of executive compensation also serves as an important signal to shareholders and stakeholders about the company’s strategic objectives and what shareholders can expect in terms of long-term value creation.

Through say-on-pay voting and company engagement, shareholders are increasingly scrutinizing remuneration decisions and demanding that pay be justified by superior performance.[a] Receiving a no vote can absorb executive and compensation committee time and attention, impact reputation, and negatively impact long- term value creation through creating distraction. Among Russell 3000 companies, 3.7 percent of proposals failed to pass in 2022, reaching an all-time high; an additional 6.0 percent received weak support (with a 50–70 percent pass rate).[1] In Germany, dissent is among the highest in Europe, with 21.6 percent of proposals failing.[2] In the public sphere, CEO pay has become a lightning rod in the media, particularly as the cost of living for average workers has risen with inflation.[b] As a consequence, CEO pay receives more attention than nearly every other routine corporate decision.[3]

Say-on-pay has become a major part of corporate governance oversight

For investors, say-on-pay voting provides an opportunity to weigh in on important corporate governance decisions at portfolio companies. For corporate boards, it presents a channel to communicate corporate strategy, performance goals, and how executives will be held responsible to achieve them. Despite these merits, say-on-pay voting as a corporate governance control mechanism is hotly debated. Proponents argue that enhanced shareholder voice, as formalized in a say-on-pay vote, and reputation concerns will help boards overcome psychological barriers to negotiating with CEOs on behalf of shareholders, resulting in more efficient compensation contracts.[4] Critics counter that say-on-pay votes will be ignored at best (since they are nonbinding) and, at worst, will cause directors to pander to shareholders, ultimately resulting in the adoption of suboptimal pay practices.[5] One thing certain is that both companies and investors have expressed frustrations with the current state of say-on-pay voting.

At the same time, say-on-pay voting has been growing globally, driven by regulations in a number of markets (exhibit 1). These regulations have sought to strike a balance of standardizing data and information in disclosures while also giving companies flexibility in setting the narrative and rationale for pay design. In the United States, a new Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) rule on pay plan disclosures went into effect in 2023, yet participants in our own working groups reported little material change in pay-for-performance analysis. The new disclosure tables and metrics were not referenced in calls between companies and investors. Disclosures in Europe under the Shareholder Rights Directive II (SRD II) framework require an explanation of how remuneration policy contributes to a business’s strategy and long-term interests.[6] The United Kingdom requires disclosures of the ratio of CEO pay to workers’ wages, in addition to standard remuneration policies. Regulations and local market practices in remuneration vary significantly across jurisdictions. Our interactions with companies and investors make it clear that more disclosure is not necessarily better disclosure, and investors often encounter gaps in the information they seek.

Companies feel constrained by proxy voting

Companies feel that they are punished for being innovative in pay plan design by so-called “nay-on- pay” votes, which may explain a lack of broad uptake of compelling options like the Norges model.[c] Straying too far from peers in pay plan design draws attention and a critical eye, even if creativity may ultimately lead to a better plan design for long-term investors. A result is cookie-cutter pay packages that don’t look very different from those of peers. One study finds a 25 percent decrease in support of say-on-pay proposals if Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) provides a negative instead of a positive recommendation.[7] Investors, in turn, reward convergence because of the difficulty associated with evaluating thousands of remuneration plans, and companies respond accordingly.[8]

The use of external consultants for pay plan design also exacerbates this trend, as such consultants tend to recommend the same models to all or most of their clients. Companies ultimately seek approval for pay plans, and a no vote is a painful outcome for leadership. Resulting pushback on compensation packages can limit the pool of candidates that corporate boards can attract and retain as CEOs.

Say-on-pay voting can overwhelm investors

From the point of view of investors, disclosures alone have proven inadequate for assessing long-term pay and performance. Important information on pay plan design, such as vesting schedules, can be difficult to extract from pay disclosures in proxy statements. Short- term shareholders are more likely to avoid monitoring or abstain from voting, shifting the responsibility and costs to long-term shareholders. Long-term investors will need to devote greater resources to building or acquiring expertise on executive compensation issues.[9] The increasing complexity of awards accumulated over multiple years, with performance conditions that potentially change from year to year, makes the development of a holistic view of pay versus performance challenging. This is not an insignificant task when voting on thousands of proxies a year. As a result, investors seek shortcuts to arrive at voting decisions and often rely on the external recommendations and analysis of proxy agencies to guide voting.

Analysis of say-on-pay voting indicates limited alignment with long-term value creation

Legislatures have mandated say-on-pay, ostensibly, as a mechanism to rein in CEO pay, yet it may have had the opposite effect. Greater disclosure of CEO pay makes it easier for company boards to set pay targets above the peer group median, leading to escalation. According to Equilar, median CEO pay over the past five years (ending in 2022) for the 100 highest-paid CEOs in the United States increased by 43 percent.[10] Overreliance on peer groups can lead pay structure to become disconnected from company strategy and circumstance.

A number of studies have considered whether shareholder votes on company executive compensation bear any significant relationship to the alignment of CEO pay with long-term shareholder interests. One study finds that shareholders guide their vote by top-line salary figures and the recommendations of proxy advisors, with scant evidence that they assess the structure of a company’s remuneration policy comprehensively or penalize badly structured policies with their binding policy vote.[11] Say-on-pay voting is sensitive to differences in pay-for-performance, but extraordinary pay premiums are required to elicit a majority no vote.[12] Shareholders do not appear to care about executive compensation unless an issuer is performing badly; the say-on-pay vote is, to a large extent, say on performance.[13]

Regardless of whether say-on-pay voting achieves the policy objectives of regulators, it does provide long-term investors the opportunity to weigh in on significant corporate governance decisions. This is important. Corporate boards have weak incentives to align executive pay with the interests of long-term shareholders. Compensation committees frequently adjust company performance numbers in complex and even obscure ways, for a variety of reasons.[14] The – at times deliberate – obfuscation of adjustments and the use of non-GAAP metrics make it more difficult for investors to peer under the hood. In the absence of an alternative, and given that say-on-pay is likely here to stay, this debate underscores the need to provide better tools and processes that investors can use to cut through the smoke screen. Later in this report, we provide suggested actions for corporate boards and investors in order to improve compensation design for the long term, and to ameliorate proxy voting and engagement.

Total shareholder return: Not the one metric to rule them all

One of the top issues that we encountered in our own working groups was the use of total shareholder return (TSR) metrics as a barometer for executive pay. This is manifested in two ways: first the use of TSR as a performance metric in pay plans, and second the use of TSR as a metric for investors and proxy advisors to evaluate pay-performance linkage. Starting with the first of these, markets have seen a significant shift over the past two decades away from grants of stock and options that vest with time and toward grants that vest with performance.[15] Despite this popularity, using TSR to measure performance is often at odds with long-term thinking. Data from Equilar points to the fact that while over half of U.S. companies use TSR as a metric to gauge executive compensation, roughly 20 percent use one- or two-year terms, and less than 2 percent use terms of five years or longer.[16]

Turning to the use of TSR as a metric for evaluating pay-for-performance linkage, investors have indicated to ISS that TSR should be the primary performance consideration in the pay-for-performance context.[17] Additionally, TSR metrics are enshrined in corporate disclosure regulations in a number of territories.

The pros and cons of TSR

TSR is easily measurable, observable, comparable, and understood by investors. It can enable firms to sharpen incentives at horizons where value added is observed, especially when meeting strategic or operational objectives is “priced in.” The common use of non-GAAP metrics means that a measurement like EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization), adjusted and adapted to performance targets, is not comparable across firms, often leaving TSR as the only alternative. Even short-term TSR can be an interim metric to assess the market view of progress toward strategy success because, theoretically, stock price measures the market’s forward views on future value creation.

Perhaps one of its biggest drawbacks is that TSR is end- and beginning-point sensitive, which could incentivize executives to manipulate share price as the performance period shifts. TSR is also an outcome measure, the market value of a company, which may not actually reflect whether strategic objectives are met or missed. Share prices are affected by many external factors, such as monetary policy, momentum, analyst opinions, or crises. Perhaps most important, TSR incentivizes executives to focus on short-term stock price rather than long-term value creation.

Working group participants pointed out that using relative instead of absolute TSR can help control for external share price shocks common to the peer group. But relativity is not the quick fix it appears to be. Executives may intentionally position their companies to cope with certain external shocks and be surprised by others. Executives paid using TSR will receive more when their companies’ stock appreciates and pays out more than those of its “peers,” and vice versa. There is still compensation for randomness, just less of it. In addition to the short-term nature of most of these metrics, peer groups are subject to interpretation – or even manipulation – because companies pursue different strategies.

Despite the shortcomings, any meaningful shift to using TSR metrics longer than three years for time-based grants is unlikely. We know from behavioral studies that executives dramatically discount deferred payments. Extending TSR to 10 years, for example, to incorporate longer-term performance would devalue the incentive towards zero for most executives.

This does not preclude investors from lengthening TSR measurement horizons in pay-for-performance analysis, though it would involve a significant amount of work on their part and go beyond typical disclosures or proxy agency reports. Lengthening horizons also calls into question what a “fair” assessment of performance is. Shareholder value creation is not typically linear – lengthening horizons can smooth the ups and downs of value creation, yet capturing such shifts using shorter measurement periods may also be warranted. On average, shareholder value creation is hill-shaped with respect to CEO tenure; extra tenure generates diminishing incremental benefits but rising incremental costs.[18] A measure of CEO performance is “fair” if it has had sufficient time to absorb all relevant financial and nonfinancial costs and benefits. CEO average tenure is also declining, from 8.0 years in 2016 to 6.9 years in 2020 [19] highlighting the practical challenges of lengthening performance periods.

Aligning companies and investors on long-term incentive design

Research suggests that having a long-term focus in pay plans leads to better long-term performance.

Academic studies support the link between long-term incentives and better long-term company performance. In most cases of going concerns, a long-term focus on incentives is warranted, particularly in industries with long investment and business cycles. One study finds that long-term pay incentives can lead to an increase in firm value and operating performance as well as an increase in firms’ investments in long-term strategies such as innovation and stakeholder relationships.[20] Another finds a positive relationship between CEO ownership and firm performance, measured as stock price.[21] Evidence also shows that high levels of shareholding and greater long-term orientation of incentive pay have a positive impact on long-term value, innovation, and the long-term orientation of companies, consistent with having a greater sense of purpose.[22] Still, some studies urge a modicum of caution in interpreting any observed correlation between executive pay and firm outcomes as a causal relationship.[23]

At an aggregate level, data from FCLTCompass shows that companies have been getting shorter term in their uses of capital, while average investor holding periods have been getting longer (exhibit 2). In a separate study, 78 percent of surveyed executives would sacrifice projects with positive net present value (NPV) if adopting them resulted in the firm’s missing quarterly earnings expectations.[24] This type of behavior seems at odds with an investor base that is increasingly focused on long- term results.

Achieving long-term incentive design

In The Risk of Rewards: Tailoring Executive Pay for Long-Term Success,[25] FCLTGlobal research shows that corporate boards can drive long-term performance by making changes to public-company executive remuneration that encourage long-term behavior. Corporate boards and long-term investors want corporate pay packages to incentivize long-term behaviors by corporate leadership – especially CEOs. Companies and investors around the world seek to ensure that this compensation is tied to long-term results.

Yet they don’t always agree on how to accomplish this goal. Remuneration design has focused on setting performance targets and vesting, which are important elements, but shareholders ultimately seek incentive alignment by rewarding leadership with long-term share ownership. For example, shareholders would like time horizons lengthened, whereas corporate directors are much more skeptical of that strategy.[26] Numerous shareholders have said they prefer simpler, long-term share aware schemes to create a long-term focus, such as the Norges model, which advocates for long-duration share grants with mandatory holding periods, even beyond resignation or retirement.[27] In practice, few corporate boards have embraced such a model despite demand from shareholders.

Practical experience suggests that the field resists adoption of a single solution to long-term pay design, which is why we took a different approach in The Risk of Rewards, looking instead at the principles of long-term pay plan design, rather than advocating for a single alternative model. Company circumstances matter greatly: a small-cap technology company’s growth and investment strategy would significantly differ from that of a large-cap utility company, and compensation packages should reflect this difference.

While a principles-based approach avoids the problem of one-size-fits-all proposals, which gain limited traction, it does create a different problem. How can investors evaluate the long-term alignment of pay programs without a deep understanding of the context of each company in which the pay plan is introduced? Complex and highly tailored remuneration design adds to the investor’s burden of pay-for-performance analysis.

Exhibit 3 breaks down the strategy of varying the time horizon of executive pay and, specifically, using time- based grants into three key areas. When setting the time horizon and structure of rewards, the performance period, the vesting period, and any mandatory holding periods are important dimensions for company boards and investors to consider.

The strongest link between shareholder wealth and executive wealth is direct stock ownership

Executives who have a significant amount of wealth tied up in shares over long periods cultivate a stronger founder and owner-operator mindset. This arrangement resembles private equity–backed companies’ structures that focus on executive wealth creation over time. Share retention policies and ownership guidelines apply globally to all vested shares that an executive holds, and mandatory holding periods are linked to specific share awards. These devices enable companies to implement share-award pay schemes like the Norges model. They also preserve the long-term focus that motivates corporate long-term incentive programs while strengthening equity awards by encouraging actions that buoy results well beyond the vesting date.[28]

Share retention policies are gaining traction as an alignment mechanism. While the most common multiple for retained shares of S&P 100 CEOs has remained six times base salary since 2015, CEO multiples greater than that are catching on.[29] A significant majority of companies in the S&P 100 (70 percent in 2021) now incorporate retention requirements into their executive stock ownership guidelines.[30] In the United Kingdom, mandatory holding periods of one to two years, linked to a specific award, have become more common. Disclosures regarding share retention policies could also be improved and become a more standardized part of proxy statements.

Pushing performance and vesting periods beyond three years is an uphill battle in most cases

The common standard of three-year vesting is not particularly short term, but it doesn’t feel long term either. Vesting periods beyond three years are less common but sometimes used for time-based grants (exhibit 4). Further delaying pay increases the risk and, in turn, the discounting of awards by executives. PwC was able to determine in a global survey of more than 1,000 executives that the average discount rate for deferred remuneration is 30 percent per annum. For example, the perceived value of a long-term incentive plan (LTIP) deferred for three years is only 50 percent of its nominal value.[31] Discounting, as well as the gap between actual and perceived value, grows when pay variability (i.e., the linking of pay to performance) is added to the equation.[32]

There is still room to improve the structure of time- based grants. Grants that fully vest in one year and that are pegged to TSR are decidedly short term in nature. Companies should carefully review such rewards for alignment with company purpose and strategy – or cease them altogether. Despite the practical challenges of lengthening performance and vesting periods beyond three years, there is room for corporate boards to experiment with such structures in cases where strategy execution and expectations of value creation warrant a longer-term incentive structure.

Actions for corporate boards

Building on our toolkit in The Risk of Rewards, board directors can replace elements of pay that are common today but are counterproductive in the long term, while applying alternative indicators to help them better structure incentives that are aligned with firm strategy and value creation. Communicating remuneration policies in a clear and simple way will make it easier for investors to analyze pay packages for more informed say-on- pay voting.

Improve long-term alignment

Do no harm: Incentive remuneration can influence an executive’s long-term behavior constructively, but it can have much wider unintended consequences, ranging from simple inefficiency and distraction to a crowding out of executives’ long-term intrinsic motivation or even encouragement of counterproductive behavior.

Doing no harm to an executive’s long-term focus is the most elementary goal of long-term remuneration design, yet several practices remain in use that pose the risk of doing that very harm:

Creating large, one-off moments of reward: These moments, such as a large vesting date or the end of a holding period, introduce short-term pressure. Rolling distributions of vested remuneration and rolling holding periods reflect long-term companies’ and investors’ priority on performance over time and avoid large paydays.

Accelerating vesting schedules upon an executive’s departure: Companies commonly accelerate vesting periods at an executive’s time of departure, creating perverse incentives to focus on maximizing the value of the firm at the end of tenure. Instead of accelerating vesting, maintaining preestablished vesting schedules will help CEOs focus on succession planning and the future state of the firm after their departure.

Assuming companies and individuals have the same time value of money and risk appetite: Individuals within the executive suite have different risk appetites and time preferences. However, these differences are even more stark when comparing how executives discount the future versus how the company does. Companies can frame questions to an executive in ways that surface the individual’s discount rate, and the first key step is recognizing that executives will have unique rates instead of assuming a rate equal to the general corporate rate.

Choose your own path: Long-term executive remuneration is specific to strategy. Equally, executives are very unlikely to align their behaviors with company strategy if their incentives reward something else. Still, in some instances, remuneration committees design and investors approve plans to pay for something other than what they want.

Relying on peer groups to determine the remuneration structure: Market data from peer groups can serve as useful input on an ex post basis, specifically when evaluating the competitiveness of pay amounts. Yet a long-term firm cannot just borrow its structure of pay from peers.

Trying to be all things to all market participants by accepting miscellaneous or conflicting provisions to appease loud voices: Investors, proxy advisers, and remuneration consultants – among many others – scrutinize companies’ remuneration plans, but fully integrating all parties’ views compromises focus of any kind and risks internal inconsistency. Long-term companies establish remuneration structures that best suit the company, its purpose, and its strategy.

Using one-year TSR as a performance metric for time- based grants, absent extraordinary circumstances: When corporate boards are focused on long-term strategy and value creation, incentives that mirror this focus are a part of structuring rewards. This could include longer-term TSR metrics in lieu of metrics that are too short term–oriented.

Use direct share ownership: Reviewing and implementing remuneration policies that rapidly build up and encourage long-term share retention is the best way to achieve alignment between executive leadership and long-term shareholders.

Undermining the effectiveness of LTIPs in the absence of share retention policies: Companies can adopt a number of tools to foster share retention, through policies either linked to specific share grants, based on retaining a minimum number of shares, or applied to shares as a multiple of salary.

Focusing on the current CEO’s tenure: Corporate boards that plan for the long term consider leadership and direction beyond the current CEO’s tenure. Share retention policies that extend beyond current tenure strengthen succession planning and alignment of strategy and priorities when somebody new takes over.

Check blind spots: Unintended consequences are rife in executive remuneration, and many are foreseeable. Remuneration design is not a panacea for short-term behaviors by executives or companies. It is important to recognize common mistakes, and to take corrective action.

Trying to motivate executives exclusively through their remuneration: Excessively focusing on remuneration can be destructive by crowding out individuals’ intrinsic motivations, which may include creating a legacy, being part of something bigger than oneself, and engaging in teamwork. Specifically, long-term companies integrate financial incentives and executives’ individual intrinsic motivations into a comprehensive package.

Overemphasizing “attraction” and “retention” in pay design: The three most cited objectives for executive remuneration are to attract top talent, align executives with long-term value creation, and retain them. Companies and executives often negotiate remuneration packages during the attract or retain phase, but these priorities are not as important over time as alignment. Long-term companies focus on using pay to shape alignment.

|

STOP… |

INSTEAD… |

|

Do no harm |

|

| Creating large, one-off moments of reward | Set vesting to smooth payouts via rolling distributions |

| Accelerating vesting schedules upon an executive’s departure | Maintain preestablished vesting schedules |

| Assuming companies and individuals have the same time value of money and risk appetite | Measure and adjust for how executives’ time values of money and risk appetites diverge from those of the company |

|

Choose your own path |

|

| Relying on peer groups to determine the remuneration structure |

Design pay structures derived from the firm’s unique purpose, strategy, and circumstances |

| Trying to be all things to all market participants by accepting miscellaneous or conflicting provisions to appease loud voices | |

| Using one-year TSR as a performance metric for time-based grants, absent extraordinary circumstances | Use longer-term TSR metrics. Experiment with TSR performance targets longer than three years where feasible |

|

Use direct share ownership |

|

| Undermining the effectiveness of LTIPs in the absence of share retention policies | Implement share ownership guidelines, share retention policies, or mandatory holding periods to cover a meaningful proportion of total executive shares held |

|

Focusing on the current CEO’s tenure |

Focus on the organization by thinking longer term, post departure. Implement share retention policies that extend past the departure or retirement of a CEO |

|

Check blind spots |

|

| Trying to motivate executives exclusively through their remuneration | Design pay structures to align with the organization’s needs and leverage the executive’s intrinsic motivation; find the right fit for the organization |

| Overemphasizing “attraction” and “retention” in pay design | |

| Avoiding risk by hiring or retaining an executive to satisfy the market | Accept the risk of hiring the right executive for the long-term strategy |

Apply alternative indicators

We present in this report two alternative indicators that compensation committees can use to help calibrate the structure of pay plans. Details on both are presented at the back of this report as separate tool kits.

Pay duration gauges the time horizon of total executive compensation, taking into account its mix of short- and long-term pay components. It measures the number of years in the future that an executive receives pay from a company, on average. Companies with longer-term investment horizons should offer longer-term incentives to match this profile. Pay duration provides one metric to assess the alignment of compensation with a long- term focus.

Wealth sensitivity assesses how an executive’s wealth responds to corporate long-term value creation, using the company’s share price as a proxy. It helps to ensure that executive pay packages provide the right incentives. Wealth sensitivity analysis can help compensation committees calibrate share-based awards. Start-up companies are short on cash but long on growth potential, and stock options may be an attractive pay instrument for their CEOs, to drive transformative strategies. Compensation that emphasizes stock options at a mature company makes less sense. Restricted stock ensures that executives feel positive and negative long- term performance equally, just as shareholders do.[33] The mix of restricted stock and stock options will yield differing sensitivities to fluctuating share prices, and companies should review this mix as a function of the firm’s risk profile as well as an executive’s intrinsic motivations.

Communicate remuneration strategy to shareholders

Receiving weak support or even a no vote from shareholders is a painful outcome for remuneration committees. Insufficient disclosure, inadequate explanations, or confusing remuneration design should not be a contributing cause to low shareholder support. Regulations have set the minimum standards for disclosure of compensation design and rationale. Yet the ultimate objective of communication includes meeting the needs of investors and stakeholders more broadly. Their interests can be better met by focusing attention on a few items.

Performance-based compensation plans are a major source of today’s complexity and confusion in executive pay.[34] When non-GAAP metrics are used, companies should provide clear explanations of targets with information to help investors reconcile them to audited financial statements. For time-based awards, investors need to fully understand how grants are earned, including vesting schedules and performance conditions. More broadly, investors need a better understanding of how compensation committees are encouraging long- term share ownership by executives. This could include a narrative about how companies build investor interest through their compensation plan designs by building restricted stock holdings, and maintain this interest through retention policies.

For each of these forms of compensation, proxy statements should clearly delineate the link to firm strategy and value creation.

Actions for investors: Simplifying say-on-pay voting with enhanced voting policies

Focus on H-QTIP: Holding Period, Quality, Targets, Instruments, and Progress

Investors have the opportunity to bring a long-term focus to proxy voting by clarifying their own proxy voting policies. By specifically stating what leads to support or rejection of remuneration proposals, investors can bring directness to the process, set expectations for engagement, and ultimately simplify the voting process by indicating where criteria are negotiable or not.

Analysts typically look at pay-for-performance in a relative way, comparing company performance and remuneration design to those of a group of peers, ideally firms of similar size and operational characteristics. Companies choose their own peer groups for proxy reporting purposes, but this practice sometimes leads to manipulation of performance targets or inflation of pay. With clear proxy voting policies, investors are better positioned to evaluate compensation based on material company features rather than just rely on peer groups.

H-QTIP is not an exhaustive list of proxy voting policies but, rather, a framework for focusing on conditions and characteristics that bring a long-term focus to remuneration design. Asset owners and managers can review individual H-QTIP criteria and use them to update their organizations’ proxy voting policies as needed. In this way, H-QTIP can serve as a screening tool to help weed out problem situations that may require more attention.

Here we examine the five elements of H-QTIP, and a detailed matrix of criteria appears at the back of this report.

Holding Period. Mandatory holding period policies linked to specific awards, or share retention policies that apply to an executive’s holdings, advance alignment between shareholders and company leadership. Share retention policies require an executive to hold shares at a multiple of salary, typically four or six times salary. Investors could engage with companies by focusing on trying to increase retention to a more meaningful level or on lengthening time horizons for holding periods linked to specific awards.

Quality. Investors are increasingly demanding that compensation be justified by superior performance. Remuneration design that is not clearly linked to operational, financial, or stakeholder goals will attract critical attention. Such a situation could include instances in which firms may be incentivizing or rewarding short- term behavior, particularly by adjusting awards in an ad hoc manner. Instances of one-off moments of reward that are not clearly linked to remuneration policy are a red flag.

Targets. Shareholders demand robust performance- based targets that embody characteristics of good remuneration design, including targets that are clearly linked to strategic, operational, and stakeholder outcomes, and that are structured to deliver long-term value creation. Targets that set a high enough hurdle provide stronger incentives for executives to achieve. Reducing targets without adequate explanation or extraordinary circumstance creates sore points.

Instruments. Shareholders are increasingly using direct share grants to foster an ownership mindset in company leaders, which help to align executives’ interests with shareholders’. From among the number of possible instruments to use in pay design, we choose to focus on share ownership as a tool for such alignment. Rewards that are structured around share grants are best positioned to rapidly build significant shareholdings over time and to foster a long-term approach to value creation. The use of stock options as an incentive instrument should be evaluated depending on company growth stage and risk profile.

Progress. Look broadly at the direction and movement of change in remuneration policies and practices. Is remuneration becoming shorter term or longer term over time, and are there reasons for investors to step up engagement efforts or escalation if problems persist? Even if policies are not yet completely aligned with long- term shareholder goals but are moving in that direction, investors can recognize positive incremental change in remuneration practices.

Review voting policies with portfolio managers and analysts

For long-term investors, the investment thesis of a company is predicated on long-term value creation that delivers better-than-average performance. Portfolio managers and research analysts of active equity strategies will have views on a company’s strategy, operations, financial health, and stakeholder engagement, and how company leadership is meeting expectations of performance. These views can be helpful in proxy voting and pay-for-performance analysis. Connecting the dots between corporate governance and stewardship teams, and portfolio management, can enhance proxy voting and more strongly align stewardship of companies with active management. Portfolio managers may also have insights in other areas, such as recent sales of shares by executives, which could also support proxy voting decision making. Reviewing updated policies with portfolio management teams is a good way to achieve alignment around a philosophy of long-term investment, as portfolio managers often bear ultimate responsibility for voting.

Apply alterative indicators

We propose, in separate toolkits at the back of this report, two alternative indicators that investors can use to evaluate pay and incentive policies: pay duration and wealth sensitivity. Investors can use pay duration to analyze the structure of a pay plan by determining, based on its components, how short or long term it is. Wealth sensitivity provides a fuller picture of executive incentives by including unvested awards and previously vested shares.

We also provide a draft letter (toolkit 3 at the back of this report) that investors may use as a template to engage with portfolio companies about pay duration. If a company’s pay duration computation falls short of expectations, investors can use this letter to directly communicate expectations with compensation committees.

Alternative indicators for say-on-pay voting

What is the best shortcut method to evaluate executive compensation packages? One of the main areas of feedback from our working groups was that investors need simplified approaches and screening tools to help weed out problem situations that may need more attention.

When deeper analysis is warranted, alternative indicators that are independent of TSR, relative TSR, and metrics typically disclosed in proxy statements can help to link executive compensation with shareholder expectations of company performance.

Indicators should be able to provide insights into executive incentives and how investment decisions are made. These include the time dimension of capital allocation and planning, as well as how pay packages are aligned – or not – with expectations for how firms operate and deliver value to shareholders. Investors should lean into evaluating pay plans in light of local market standards and practices, which can vary considerably. Companies can use indicators as internal guidelines.

Companies and investors need indicators and approaches with these characteristics:

- Are easy to interpret, compare, and use

- Measure strategy execution instead of just financial outcomes (like TSR) which may not necessarily reflect whether strategic objectives have been met

- Can be aligned with underlying strategic initiatives that management must accomplish in order to drive improved enterprise value or the quality of management execution

- Are not just backward but forward looking and analyze the structure and time horizon of pay packages

- Capture portfolio and wealth effects arising from previously granted equity (which cannot be ignored as they are typically far stronger and more significant than current realized pay)

- Can be based on existing data and disclosures

Investors also need to understand the structure of pay and whether it makes sense for the type of company and its life cycle stage, market cap, capital allocation cycle, and industry.

Pay duration

Executive pay duration is a forward-looking and simple metric that provides insight into whether pay plans are shorter term or longer term in their orientation. Based on the work of Gopalan and colleagues (2014), pay duration reflects the vesting periods and time horizons of different pay components – salary, bonus, and LTIP – quantified in a single metric measured in years.[35] It is computed as a weighted average, in years, restating the pay quantum in terms of its components. The authors of this study find that pay duration is longer in firms with more growth opportunities, more long-term assets, and greater R&D intensity; in less risky firms; and in firms with better recent stock performance.

This indicator is not backward looking like most common pay metrics, but is instead a tool for analyzing the forward structure of pay. Gopalan and others (2014) find that pay duration is short in absolute terms, just 1.44 years on average, but that it varies by industry and tends to be correlated with project and asset duration (exhibit 6).[36]

When evaluating a company’s investment cycle and strategic objectives, pay duration can provide context for comparison. For example, if a company is ramping up investment in R&D, it should structure executive incentives in a way that matches a lengthening investment horizon, thus increasing the resulting pay duration. Pay duration can also be applied as a screening tool for comparing pay profiles of companies in a peer group to see how incentives are structured on a relative basis.

Wealth sensitivity

Investors pay significant attention to the current compensation of executives – what they will be earning given proposed pay packages and the vesting of previous grants. Yet a major part of a CEO’s incentive package is the indirect effects of changes in the value of shareholdings, rather than the “flow” measure of compensation vesting during the year.[37] A long-tenured CEO, like Tim Cook for example, has accumulated, over time, significant wealth — in this case, in Apple stock, reportedly around US$1.8 billion.[38] This amount far exceeds any measure of flow pay. Indeed, the change in value of accumulated wealth likely acts as a stronger incentive than current measures of pay. Yet this phenomenon is often overlooked in pay-for-performance analysis, or calibration of compensation.

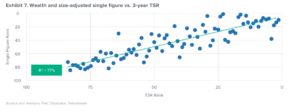

Accumulated wealth is a strong driver of individual executive risk appetites, time values of money, and intrinsic motivations. A study by PwC finds that there is a stronger pay-for-performance link when previously granted equity is included in CEO pay analysis; this link is known as the “wealth effect” (exhibit 7). “Using realized pay, and adjusting for company size and previously awarded equity means that we have now explained nearly four-fifths of the variation in pay rank by performance.”[39]

Wealth sensitivity, presented as an indicator, can help to explain how significant the effects of fluctuating share price are on an executive’s total wealth. A 2010 study found that with a 1 percent change in share price, the average wealth of CEOs in the 100 largest companies in the United States changed by US$640,000.[40]

An even more informative method is to consider the change in wealth given larger fluctuations in share prices. Shareholders realize a one-for-one change in wealth with changes in stock price, yet CEOs may experience a different profile, given their different pay instruments. Stock options will significantly alter the wealth profile of executives. Share grants will contribute to a profile that is similar to that of shareholders.

Way forward and conclusion

Technology solutions to fill data gaps

The authors of previous studies cited in this paper cobbled together executive compensation data from various sources including Equilar, public filings, and other public sources. In some cases, they pieced together complementary datasets in order to get around data gaps and create a whole, workable pool of data. The proxy agencies ISS and Glass Lewis maintain databases for compensation data, gleaned from proxy statements and regulatory filings. Despite these sources, participants in FCLTGlobal working groups expressed frustration with data that is often scattered or incomplete. This situation poses a major challenge to investors who wish to perform independent analysis of executive compensation and performance based on raw data. It also contributes to investor reliance on proxy agency recommendations.

Artificial intelligence (AI) could be applied to scrape and process dispersed and unstructured data from regulatory filings in order to present data in an organized and standardized way. Such a process is already underway in the ESG space. In particular, tools could be developed to identify gaps in compensation data and trained to fill them.

The role of proxy agencies

Mentioned throughout this report, the proxy agencies hold significant sway in say-on-pay voting and compensation design through their recommendations. The actions and tools outlined in this report are targeted to corporate boards and investors, yet they are just as relevant to the proxy agencies, particularly on issues of data. Indeed, resolving these issues could be a core strategic plank for the proxy agencies. The tools we present in this report, pay duration and wealth sensitivity, have complex data needs. But they need not be so complex given the availability of existing technologies like machine learning and AI. The proxy agencies could lead in this regard, developing technology solutions to broaden tools available to companies and investors alike.

Conclusion

Since 2020, FCLTGlobal has convened members, including companies, professional services providers, asset owners, and asset managers, on the topic of executive remuneration. This final publication reflects the culmination of several years of work and builds on our previous publication, The Risk of Rewards. Companies need to consider how to reorient their pay programs to align with strategy and encourage long-term stock ownership by executives. Shareholders need to evaluate pay programs in a way that encourages lengthened time-horizons of decision making and alignment of total executive wealth with shareholder interests. The toolkits this report provides have been designed for corporate boards and investors alike, in order to bring a long-term focus to executive remuneration design and proxy voting.

First and foremost, the tools in this report focus on the dimensions and time horizons of pay – performance period, vesting, and mandatory share retention policies. The research concludes that replacing short term–oriented approaches with direct long-term stock ownership by executives is a better solution to achieving alignment of incentives with long-term shareholders.

Corporate boards can set remuneration policies and practices that further a long-term focus:

- Improve long-term alignment by replacing short-term and counterproductive practices in executive remuneration

- Gauge compensation structure and incentives through alternative indicators like pay duration and wealth sensitivity

- Streamline corporate disclosures of pay practices and focus on the decision-making narrative

Investors require simplified approaches to say-on-pay voting that are aligned with long-term remuneration design. Setting proxy voting policies is a critical step to achieve better alignment. Our H-QTIP toolkit (toolkit 2 at the back of this report) provides a set of voting policies that focus on the most important elements of long-term remuneration design – holding period, quality, targets, instruments, and progress. Investors can use these criteria to update their own proxy voting guidelines. Doing so is a critical step to take: by clearly stating in writing what criteria are likely to lead to a no or yes vote, investors can lean into a set of principles that drive proxy voting and contribute to positive change at portfolio companies.

Endnotes

aThroughout this paper, “pay-for-performance” refers to the practice of justifying compensation in terms of the performance of the company. Investors who undertake pay-for-performance analysis seek to understand how closely compensation is correlated to the impact executive leadership has on a firm’s performance.(go back)

bExecutive pay levels (i.e., the quantum of remuneration) are an interesting and important topic, but not something we treat with depth in this report. Future work at FCLTGlobal could tackle the issue of escalating CEO pay, using a cross-value-chain approach that also considers escalating pay in asset management. We refer readers to our report The People Factor: How Investing in Employees Pays Off, which explores the role of labor practices in corporate value creation.(go back)

cNorges Bank Investment Management, the sovereign wealth fund that stewards Norway’s oil and gas revenues, pioneered an alternative method of determining executive compensation that focuses on cultivating an ownership mindset and using time-centered share grants (i.e., shares with ownership over a long duration). In its 2017 position paper, Norges emphasized, “A substantial proportion of total annual remuneration should be provided as shares that are locked in for at least five and preferably ten years, regardless of resignation or retirement. … Allotted shares should not have performance conditions and the complex criteria that may or may not align with the company’s aims” (“CEO Remuneration: Position Paper.” Norges Bank Investment Management, April 7, 2017. https://www.nbim.no/en/responsible-investment/ position-papers/ceo-remuneration/.).(go back)

1Todd Sirras, Austin Vanbastelaer, Justin Beck, Sarah Hartman, Kyle McCarthy, and Alexandria Agee. “2022 Russell 3000 Average Vote Results Decline as Failure Rates Reach Historic High.” Reports & Downloads 8, Semler Brossy, January 12, 2023. https://semlerbrossy.com/insights/2022-say-on-pay-report/.(go back)

2Paul Guiziou, Vanessa Horsinka, and Sofian Ounaha. “2022 European Voting Results Report.” ISS Insights, January 23, 2023. https://insights.issgovernance.com/posts/2022-european-voting-results-report/.(go back)

3Alex Edmans, Tom Gosling, and Dirk Jenter. “CEO Compensation: Evidence from the Field.” Finance Working Paper no. 771/2021, Brussels: European Corporate Governance Institute, May 2023. https://papers.ssrn.com/ sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3877391.(go back)

4Fabrizio Ferri and David A. Maber. “Say on Pay Votes and CEO Compensation: Evidence from the UK.” Review of Finance 17, no. 2 (2013), 527–563. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfs003.(go back)

5 Ibid.(go back)

6Glass Lewis. SRD II – Say on Pay Requirements. San Francisco, n.d. https://www.glasslewis.com/wp-content/ uploads/2020/02/SRDII_SoP.pdf. Accessed 11 July 2023.(go back)

7Nadya Malenko and Yao Shen. “The Role of Proxy Advisory Firms: Evidence from a Regression-discontinuity Design.” Review of Financial Studies 29, no. 12 (December 2016): 3394–3427, https://www.nadyamalenko. com/Malenko,Shen%20(RFS%202016).pdf. The study finds the convergence toward ISS standards is accentuated if the firm is likely to receive a negative proxy advisor recommendation in the absence of a policy change, if directors received below-median support at the previous annual meeting, and if the firm has above-median ownership by dispersed investors.(go back)

8David Larcker, Allan McCall, and Gaizka Ormazabal, “Outsourcing Shareholder Voting to Proxy Advisory Firms,” Journal of Law and Economics 58, no. 1 (February 2015): 173–204, https://doi.org/10.1086/682910.(go back)

9Keith L. Johnson and Daniel Summerfield. “Shareholder Say on Pay – Ten Points of Confusion.” Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance, Cambridge, MA, n.d. https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/wp-content/ uploads/2008/11/say-on-pay-ten-points.pdf. Accessed 8 August 2023.(go back)

10Adam Hearn. “Equilar, CEO Pay Trends – , July 2022.” Meridian Compensation Partners, August 18, 2022. https://www.meridiancp.com/insights/equilar-ceo-pay-trends-july-2022/.(go back)

11Carsten Gerner-Beuerle and Tom Kirchmaier. “Say on Pay: Do Shareholders Care?” Finance Working Paper no. 579/2018. Brussels: European Corporate Governance Institute, November 2018. https://www.ecgi.global/ sites/default/files/working_papers/documents/finalgerner-beuerlekirchmaier.pdf.(go back)

12Stephen F. O’Byrne. “Say on Pay: Is It Needed, Does It Work?” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 30, no. 1 (Winter 2018), 30–38. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jacf.12275.(go back)

13Jill E. Fisch, Darius Palia, and Steven Davidoff Solomon. “Is Say on Pay All About Pay? The Impact of Firm Performance.” Penn Carey Law Legal Scholarship Repository, Philadelphia, 2018. https://scholarship.law. upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2933&context=faculty_scholarship.(go back)

14Robert C. Pozen and S.P. Kothari. “Decoding CEO Pay.” Harvard Business Review, July–August 2017. https:// hbr.org/2017/07/decoding-ceo-pay.(go back)

15Mihir A. Desai, Mark Egan, and Scott Mayfield. “A Better Way to Assess Managerial Performance.” Harvard Business Review, March–April 2022. https://hbr.org/2022/03/a-better-way-to-assess-managerial- performance.(go back)

16Sarah Keohane Williamson. “Why Basing CEO Pay on Stock Performance Rarely Works.” Forbes, March 10, 2021. https://www.forbes.com/sites/sarahkeohanewilliamson/2021/03/10/tsr-based-pay-is-not-a-short-cut-for- shareholders-or-stakeholders/.(go back)

17Pay-for-Performance Mechanics: ISS’ Quantitative and Qualitative Approach. Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), January 13, 2023. https://www.issgovernance.com/file/policy/active/americas/Pay-for- Performance-Mechanics.pdf.(go back)

18Paul Kerin. “How Long Should CEOs Stay?” Australian Institute of Company Directors, September 1, 2015. https://www.aicd.com.au/regulatory-compliance/superannuation-industry-supervision-act/1993/how-long- should-ceos-stay.html.(go back)

19https://www.kornferry.com/insights/this-week-in-leadership/where-have-all-the-long-tenured-ceos-gone.(go back)

20Caroline Flammer and Pratima Bansal. “Does a Long-Term Orientation Create Value? Evidence from a Regression Discontinuity.” Unpublished, September 11, 2016. Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers. cfm?abstract_id=2511507.(go back)

21Ulf von Lilienfeld-Toal and Stefan Ruenzi, “CEO Ownership, Stock Market Performance, and Manager Discretion.” The Journal of Finance 69, no. 3 (2014): 1013–1050. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ jofi.12139.(go back)

22Clare Chapman, Alex Edmans, Tom Gosling, Will Hutton, and Colin Mayer. The Purposeful Company: Executive Remuneration Report. London: The Purposeful Company, February 2017. https:// thepurposefulcompany.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/feb-26_tpc_exec-rem-final-report_v3-tg-2.pdf.(go back)

23Alex Edmans, Xavier Gabaix, and Dirk Jenter. “Executive Compensation: A Survey of Theory and Evidence.” Finance Working Paper no. 514/2016. Brussels: European Corporate Governance Institute, 2017. Revised June 30, 2021. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2992287.(go back)

24John R. Graham, Campbell R. Harvey, and Shivaram Rajgopal. “The Economic Implications of Corporate Financial Reporting.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 40, no. 1–3 (January 11, 2005): 3–73. https:// papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=491627.(go back)

25The Risk of Rewards: Tailoring Executive Pay for Long-Term Success. Boston: FCLTGlobal, 2021. https://www. fcltglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Risk-of-Rewards_FCLTGlobal.pdf.(go back)

26Graham, Harvey, and Rajgopal. “The Economic Implications of Corporate Financial Reporting.”(go back)

27Norges Bank Investment Management. “CEO Remuneration.” Position paper. April 7, 2017. https://www.nbim. no/en/responsible-investment/position-papers/ceo-remuneration/.(go back)

28Dan Leon and LaToya Scott. “CEO Stock Incentives Increasingly Tied to Stock Ownership and Retention.” Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance, Cambridge, MA, February 15, 2020. https://corpgov. law.harvard.edu/2020/02/15/ceo-stock-incentives-increasingly-tied-to-stock-ownership-and-retention/.(go back)

29Dan Leon and LaToya Scott. “S&P 100 Executive Stock Ownership Guidelines: 2015–2021.” WTW, December 13, 2021. https://www.wtwco.com/en-us/insights/2021/12/s-p-100-executive-stock-ownership-guidelines-2021.(go back)

30Ibid.(go back)

31PwC. Making Executive Pay Work. London. 2012. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/hr-management-services/ publications/assets/making-executive-pay-work.pdf.(go back)

32Edmans, Gabaix, and Jenter, “Executive Compensation.”(go back)

33Council of Institutional Investors, “Policies on Corporate Governance,” March 6, 2023. https://www.cii.org/ corp_gov_policies.(go back)

34Ibid.(go back)

35Radhakrishnan Gopalan, Todd T. Milbourn, Fenghua Song, and Anjan V. Thakor. “Duration of Executive Compensation.” The Journal of Finance 69, no. 6 (2014): 2777–2817. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers. cfm?abstract_id=2198397.(go back)

36Ibid.(go back)

37PwC. Paying for Performance: Demystifying Executive Pay. London. February 2017. https://static1. squarespace.com/static/5f510ee5dafd55157d251a1d/t/5f6b87b8e5384d49e3a31e86/1600882647642/ Paying+for+performance.pdf.(go back)

38Daniel Pereira. “Who Owns Apple?” The Business Model Analyst, March 3, 2023. https:// businessmodelanalyst.com/who-owns-apple/#:~:text=if%20exercised%20fully.-,Tim%20Cook,net%20 worth%20of%20%241.8%20billion.(go back)

39PwC, Paying for Performance.(go back)

40David F. Larcker and Brian Tayan. “Sensitivity of CEO Wealth to Stock Price: A New Tool for Assessing Pay for Performance.” Stanford Closer Look Series. Stanford University, September 15, 2010. https://www.gsb. stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publication-pdf/cgri-closer-look-10-ceo-wealth-stock-price.pdf(go back)

Print

Print