Brian Breheny, Raquel Fox and Joseph Yaffe are Partners at Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP. This post is based on their Skadden memorandum.

Prepare for New Pay-Versus Performance Disclosures

On August 25, 2022, the SEC adopted final rules requiring public companies to disclose the relationship between the executive compensation actually paid to the company’s named executive officers (NEOs) and the company’s financial performance. The final rules implement the “Pay Versus Performance” disclosure requirements mandated by Section 953(a) of the DoddFrank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act enacted in 2010 (Dodd-Frank Act).

Overview

Item 402(v) of Regulation S-K contains the “Pay Versus Performance” disclosure requirements. The new requirements consist of three components: (i) a pay-versus-performance table that includes metrics from the previous five fiscal years such as CEO and NEO compensation “actually paid,” cumulative total shareholder return (TSR) for the company and its peer groups, financial performance measures and the company’s net income; (ii) a description of the relationship between compensation “actually paid” and the company’s performance metrics; and (iii) a tabular list of important financial measures that the company selected to link the compensation “actually paid” with the performance metrics. The three components are described in detail below.

Covered Issuers and Fiscal Years

Calendar-year companies should prepare to implement these new disclosure items in their 2023 proxy statements with respect to compensation paid in fiscal year 2022. Companies generally will be required to disclose the applicable information for their five most recently completed fiscal years, provided that in the first proxy or information statement in which a company provides this disclosure, it may provide the newly required disclosure for three years instead of five years, adding another year of disclosure in each of the two subsequent annual filings.

All reporting companies that file proxies or information statements that require executive compensation disclosure are required to comply with this new rule. However, smaller reporting companies are subject to scaled disclosure requirements, including a three-year period subject to a phase-in period for the first applicable filing in which disclosure for only the two most recently completed fiscal years is required. Smaller reporting companies are also not required to provide the peer group TSR or a company-selected measure in the new table.

Emerging growth companies, foreign private issuers and registered investment companies (other than business development companies) are entirely exempt from the new disclosure requirements.

For newly public companies, disclosure is required only for the years in which the company was a reporting company pursuant to Section 13(a) or Section 15(d) of the Exchange Act. For example, for a company that completed an initial public offering (IPO) in 2022 that is not an emerging growth company, foreign private issuer or registered investment company, disclosure in the first applicable filing will be required only for 2022 (for the period following the IPO date), with each subsequent annual proxy filing including disclosure for an additional year until five years of disclosure (or three years in the case of a smaller reporting company) are provided.

Component One: Pay-Versus-Performance Table

The final rules require companies to include a new “Pay Versus Performance” table in proxy or information statements that are required to include executive compensation disclosure.

Companies must include the following information for each covered fiscal year (i.e., for proxy statements filed in 2023, the covered fiscal years are 2022, 2021 and 2020):

- the total compensation of the CEO as reported in the “Total” column of the “Summary Compensation Table” (SCT) (if more than one person served as CEO during the most recent fiscal year, a separate column must be included in the Pay Versus Performance table for the total compensation paid to each CEO);

- the average total compensation of the other NEOs using the average of the amounts reported in the “Total” column of the SCT for the applicable year for each other NEO;

- the compensation “actually paid” to the CEO (if more than one person served as CEO during the most recent fiscal year, a separate column must be included in the table for the compensation “actually paid” to each CEO);

- the average total compensation “actually paid” to the other NEOs using the average of the compensation “actually paid” to each other NEO for the applicable year; – the cumulative TSR, calculated in the same manner as the performance graph already required pursuant to Item 201(e) of Regulation S-K;

- the cumulative TSR of the company’s “peer group”; for its peer group, the company must use either (a) the same index or issuers used by the company for purposes of its disclosure already included in the Form 10-K pursuant to Item 201(e)(ii) of Regulation S-K or (b) if applicable, the company’s peer group used for purposes of its disclosure in the Compensation Discussion and Analysis (CD&A) pursuant to Item 402(b)(2) (xiv) of Regulation S-K;

- the net income of the company for the applicable year;

- a financial performance measure selected by the company (Company-Selected Measure) that in the company’s assessment represents the single most important financial performance measure (not otherwise already included in the table (e.g., net income or absolute or “peer group” TSR)) that the company used for the most recent fiscal year to link compensation actually paid to the company’s NEOs to the company’s performance;

- additional financial performance measures other than the Company-Selected Measure may be included in additional columns to the table, provided that the additional columns and related disclosure are clearly identified as supplemental, not misleading and not presented with greater prominence than the required Company-Selected Measure; and

- footnote disclosure to the table for any amounts deducted and added to total compensation of the NEOs to determine the amount of compensation “actually paid” (as described below) and certain related assumptions, as well as the name of each CEO and other NEO included in the table for each year and the fiscal year for which they were included.

For the TSR columns in the new table, the TSR for the earliest year in the table will represent the one-year TSR, the TSR for the next year in the table will represent the two-year TSR, and so forth, such that the TSR for the most recent fiscal year in the table will represent the cumulative TSR for the entire applicable period covered in the table. The table should weight peer group TSR based on the initial market capitalization of each peer group company as of the beginning of the earliest year included in the table. If the company uses a different peer group than the peer group used for the prior fiscal year, the company must explain the reason for the change in a footnote and provide comparison information with respect to both the old and the new peer group.

Companies should calculate executive compensation “actually paid” for the purposes of the Pay Versus Performance table using the amounts reported for the CEO and each other NEOs in the “Total” column of the SCT for the applicable year, but adjusted as follows for amounts in (i) the “Stock Awards” and “Option Awards” columns of the SCT for the applicable year and (ii) the “Change in Pension Value” column of the SCT for the applicable year:

For stock and options awards:

- subtract: the grant date fair value of equity awards granted during the applicable year that appears in the SCT for the applicable year;

- add: (i) the year-end fair value of any equity awards granted in the applicable year that are outstanding and unvested as of the end of the applicable year (for awards subject to performance conditions, based on the probable outcome of such conditions); (ii) the amount of change as of the end of the applicable year (from the end of the prior year) in the fair value (whether positive or negative) of any awards granted in prior years that are outstanding and unvested as of the end of the applicable year; (iii) for awards that are granted and vest in the same year, the fair value as of the vesting date; (iv) for awards granted in prior years that vest in the applicable year, the amount equal to the change in the fair value (whether positive or negative) as of the vesting date (from the end of the prior year); and (v) any dividends or other earnings paid on equity awards in the applicable year prior to the vesting date that are not otherwise reflected in the fair value of such awards or included in any other component of total compensation for the applicable year;

- subtract: the amount equal to the fair value at the end of the prior year of any awards that fail to meet the vesting requirements and are forfeited in the applicable year.

For defined benefit and actuarial pension value:

- subtract: the positive amount of any aggregate change in the actuarial present value of defined benefit and actuarial pension plans that appears in the SCT for the applicable year;

- add back: (i) the actuarially determined pension service cost for services rendered during the applicable year; and (ii) any prior service costs introduced in connection with a plan amendment or initiation during the applicable year, regardless of whether any of the pension benefits are currently vested;

- subtract: the amount of any credit for reduced benefits introduced in connection with a negative plan amendment during the fiscal year.

Component Two: Description of the Relationship Between Pay and Performance

Using values reflected in the Pay Versus Performance table described above, companies must describe (i) the relationship between (a) the executive compensation “actually paid” to the CEO and the average total compensation “actually paid” to the other NEOs and (b) the company’s TSR, its net income and the Company-Selected Measure and (ii) the relationship between the company’s TSR and the TSR of its peer group.

Companies must also describe the relationship between (i) the executive compensation actually paid to the CEO and the average total compensation actually paid to other NEOs and (ii) any supplemental measures voluntarily included in the new table in addition to the required Company-Selected Measures. Smaller reporting companies are only required to describe (i) the relationship between the executive compensation actually paid to the CEO and the average total compensation actually paid to the other NEOs and (ii) the company’s TSR and net income.

Companies can describe these relationships either through a narrative discussion, a graphical presentation or a combination of both. The relationship disclosures may be grouped together, as long as any combined description of multiple relationships is clear.

Component Three: Tabular List of Important Financial Measures

Every company also must provide an unranked tabular list of at least three, but no more than seven, financial performance measures that in the company’s assessment represent the most important financial measures used by the company for the most recent fiscal year to link compensation actually paid to the company’s CEO and other NEOs to the company’s performance.

Companies may include nonfinancial performance measures in the tabular list if those measures are among the most important measures used by the company to link compensation actually paid to the performance and the company has disclosed at least three financial performance measures (or fewer if the company uses fewer than three measures).

The Company-Selected Measure disclosed in the Pay Versus Performance table described above must be one of the financial performance measures included in the tabular list. There are no additional disclosure requirements if the company changes the Company-Selected Measure from year to year.

Companies are not required to provide the methodology used to calculate the financial performance measures included in the tabular list but should consider if that disclosure would be helpful to understand the financial performance measures or necessary to prevent them from being confusing or misleading. If the Company-Selected Measure is not a GAAP financial measure, high-level disclosure must be provided regarding how the numbers are calculated from the company’s audited financial statements, but full GAAP reconciliation is not required.

Companies that consider fewer than three financial performance measures when linking compensation to company performance are required to list only the number of financial performance measures actually considered, and a company that does not use any financial performance measures to link compensation actually paid to performance in the most recent fiscal year is not required to present a tabular list or disclose a Company-Selected Measure. Smaller reporting companies are also not required to provide a tabular list or disclose a Company-Selected Measure.

Location of Pay-Versus-Performance Disclosure

The rules provide flexibility to companies regarding the location of the new disclosure in the proxy statement. The disclosure is not required to be included in CD&A, because including the disclosure in the CD&A may cause confusion by suggesting that the company considered the pay-versus-performance relationship in its compensation decisions for the applicable fiscal year, which may or may not be the case for all of the relationships required to be described other than the Company-Selected Measure.

Supplemental Disclosures

Companies may supplement the new disclosure by providing pay-versus-performance disclosure (in tabular format or otherwise) based on other compensation measures such as “realized pay” or “realizable pay” if they believe that such supplemental disclosures would provide useful information about the relationship between the compensation paid and the company’s financial performance. The supplemental disclosure, however, may not be misleading or presented more prominently than the required new disclosure. This prominence requirement should be given particular consideration by companies with pay-for-performance discussions in the executive summaries of their proxy or information statements and may require companies to modify the way they disclose performance information in the CD&A.

Applicable Filings

The new pay-versus-performance disclosure is required in any proxy or information statement that is required to include executive compensation disclosure, including those with respect to the election of directors. The disclosure is not required in annual reports on Form 10-K (other than with respect to the incorporation of proxy disclosure by reference), Securities Act registration statements or Exchange Act registration statements (e.g., registration statements on Form S-1 for IPO companies). The disclosure also will not be deemed to be incorporated by reference into any filing under the Securities Act or the Exchange Act, except to the extent that the company specifically incorporates it by reference.

XBRL

The new disclosure must be tagged in interactive data format using Inline eXtensible Business Reporting Language (Inline XBRL). Smaller reporting companies may phase in Inline XBRL tagging.

Implications

The new disclosure requirements regarding pay versus performance became effective on October 11, 2022. Companies should prepare to incorporate these new items into those proxy or information statements that include executive compensation disclosure for fiscal years ending on or after December 16, 2022, meaning that calendar year companies will need to include this new disclosure in their proxy statements filed in 2023.

Incorporate Lessons Learned From the 2022 Say-on-Pay Votes and Compensation Disclosures and Prepare for 2023 Pay Ratio Disclosures

Companies should consider their recent annual say-on-pay votes and best practices for disclosure when designing their compensation programs and communicating about those programs to shareholders. This year, companies should understand key say-on-pay trends, including overall 2022 say-on-pay results, factors driving say-on-pay failure (i.e., those say-on-pay votes that achieved less than 50% shareholder approval), say-on-golden-parachute results and results of equity plan proposals, as well as recent guidance from the proxy advisory firms Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) and Glass Lewis.

Overall Results of 2022 Say-on-Pay Votes

Below is a summary of the results of the 2022 say-on-pay votes from Semler Brossy’s annual survey[1] and trends over the last 11 years since the SEC adopted its say-on-pay rules. Overall, say-on-pay results at Russell 3000 companies surveyed in 2022 were generally the same or slightly below those in 2021.

- Approximately 96.5% and 97.2% of Russell 3000 companies in 2022 and 2021, respectively, received at least majority support on their say-on-pay votes, with approximately 93% receiving above 70% support in 2021 and 90% receiving above 70% support in 2022. This demonstrates slightly reduced say-on-pay support in 2022 compared with 2021.

- To date thus far in 2022, approximately 86.5% of Russell 3000 companies and 87.5% of S&P 500 companies have received “For” recommendations by ISS, a slight decrease from the 89% “For” average experienced in 2021.

- Russell 3000 companies received an average vote result of 89.4% approval in 2022, which is slightly lower than the average vote result of 90.4% approval in 2021.

- The average vote result exceeded 90% approval in 2022 across multiple industry sectors, including utilities, materials, energy, financials and real estate.

- The communication services sector featured the lowest level of average support, at 88.5%, compared with other industry sectors.

- As of September 2022, approximately 3.5% of say-on-pay votes for Russell 3000 companies failed in 2022, which was slightly higher than the 2.8% failure rate for 2021 measured in September 2021.

- Approximately 12% of Russell 3000 companies and 15% of S&P 500 companies surveyed have failed to receive a majority support for say-on-pay at least once since 2011.

- 39% of S&P 500 companies and 32% of Russell 3000 companies surveyed have received less than 70% support in a say-on-pay vote at least once since 2011.

Factors Driving Say-on-Pay Failure

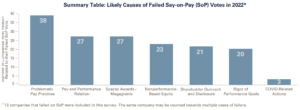

Overall, the most common factors voters used to reject say-on-pay proposals were problematic pay practices, pay and performance relation, special awards, non-performance-based equity, shareholder outreach and disclosure, rigor of performance goals and COVID-19-related actions, as summarized in the chart below.[2]

Consistent with 2021 results, the three leading causes of say-on-pay failure for 2022 are problematic pay practices, pay and performance relations, and special awards. Notably, non-performance-based equity took a leap from the seventh leading cause to third in 2022, while COVID-19 related actions, significantly decreased in number from 18 to 3.

ISS Guidance

When evaluating pay practices, the focus of proxy advisory firms tends to center on whether a company’s practices are contrary to a performance-based pay philosophy. In December of each year, ISS publishes FAQs to help shareholders and companies understand changes to ISS compensation-related methodologies. In December 2021, ISS published its most recent general United States Compensation Policies FAQ,[3]which included the following key updates:

- ISS indicated that there are no changes to the three primary quantitative pay-for-performance screens (RDA, MOM and PTA) for 2022. For meetings on or after February 1, 2022, there are slight updates to the “Eligible for FPA Adjustment” thresholds under the FPA measure.[4]

- ISS highlighted three problematic practices that carry “significant weight” and are likely to result in an adverse say-on-golden-parachute recommendation, in and of themselves, including:

- Golden parachute excise tax gross-ups are estimated to be paid (based on amounts reported in the golden parachute tables of the merger proxy).

- Cash severance payments are triggered solely by the occurrence of a change in control (i.e., “single trigger”) without disclosure indicating the executive will incur a termination in connection with the transaction.

- Single-trigger acceleration of performance-based awards at an above-target level has occurred without disclosure of compelling rationale.

- ISS described how it accounts for a variety of pay-forperformance considerations and other factors as it evaluates proposals seeking approval of individual equity awards on a case-by-case basis, which may include (without limitation):

- the transparency and clarity of disclosure;

- the magnitude of pay opportunities;

- the prevalence and rigor of performance vesting criteria;

- the existence of shareholder-friendly guardrails and termination/CIC provisions;

- the estimated cost of the award and/or its dilutive impact; and

- any other factors deemed relevant.

Exceptionally large awards and “front-loaded” awards in this context are subject to heightened pay-for-performance considerations, as is the case with ISS’ approach to analyzing such awards in the context of the qualitative pay-for-performance evaluation.

- ISS indicated that it continues to assess pandemic-related pay decisions based on its “U.S. Compensation Policies and the COVID-19 Pandemic — Updated for 2022 U.S. Proxy Season” FAQ published on December 7, 2021. Highlights from this publication include:

- As in the pre-COVID-19 era, ISS will generally view midyear changes to metrics, performance targets and measurement periods, as well as programs that emphasize discretionary or subjective criteria, negatively. In certain circumstances, ISS will view lower preset performance targets (as compared to 2020) and/or modest year-over-year increases in the weighting of subjective or discretionary factors as reasonable for companies that continued to incur severe economic impacts and uncertainties as a result of the pandemic in 2021.

- If midyear adjustments to annual incentive programs are made, ISS encourages companies to explain the necessity for such actions, including the specific pandemic-related challenges that arose and how those challenges rendered the original program design obsolete or the original performance targets impossible to achieve, as well as how changes to compensation programs are not reflective of poor management performance.

- ISS will continue to view changes to in-progress long-term incentive cycles negatively, particularly for companies that exhibit a quantitative pay-for-performance misalignment. ISS may view modest alterations to cycles going forward as reasonable if a company continues to incur severe negative impacts over a long-term period.

- For companies that made changes to compensation programs that normally would be viewed as concerning from a pay-for-performance standpoint, ISS may consider a company’s intentions to return to a strongly performancebased incentive program going forward as a mitigating factor.

- As ISS requires for one-time awards granted outside the context of the pandemic, companies that grant one-time awards should disclose the rationale for doing so (including the magnitude and structure of the award), as well as how the award furthers investors’ interests. ISS will view the granting of one-time awards to replace forfeited incentives and/or insulate executives from lower pay outcomes as a problematic action.

- ISS’ policy regarding responsiveness to say-on-pay proposals remains consistent with prior years regarding the first two factors (i.e., disclosure of the board’s shareholder engagement efforts and disclosure of the specific feedback received from dissenting investors). Regarding the third factor (i.e., any actions or changes made to pay programs and practices to address investors’ concerns), ISS will return to its pre-pandemic application, where companies must demonstrate actions that address investors’ feedback.

ISS’ general United States Compensation Policies FAQ summarized which problematic practices are most likely to result in an adverse ISS vote recommendation. As described in FAQ No. 45, problematic practices include the following, which are expected to remain problematic in 2023:

- repricing or replacing of underwater stock options or stock appreciation rights without prior shareholder approval (including cash buyouts and voluntary surrender of underwater options);

- excessive or extraordinary perquisites or tax gross-ups;

- new or extended executive agreements that provide for (i) termination or change-in-control severance payments exceeding three times the executive’s base salary and bonus, (ii) change-in-control severance payments that do not require involuntary job loss or substantial diminution of duties, (iii) a definition of “good reason” termination that presents windfall risks, such as definitions triggered by potential performance failures (e.g., company bankruptcy or delisting), (iv) changein-control excise tax gross-up entitlements (including “modified” gross-ups), (v) multiyear guaranteed awards or increases that are not at risk due to rigorous performance conditions or (vi) a liberal change-in-control definition combined with any single-trigger change-in-control benefits;

- insufficient executive compensation disclosure by externallymanaged issuers (EMIs) such that a reasonable assessment of pay programs and practices applicable to an EMI’s executives is not possible; or

- any other provision or practice deemed to be egregious and a significant risk to investors.

ISS is expected to release a full set of updated compensation FAQs in December 2022, which will provide robust guidance for 2023.

Glass Lewis Guidance

Glass Lewis published its “2023 Policy Guidelines for the United States” in November 2022, which included the following compensation updates in effect for the 2023 proxy season:[5]

- Glass Lewis updated its approach to proposals requesting that companies adopt a policy whereby shareholders must approve severance payments exceeding 2.99 times the amount of the executive’s base salary plus bonus. Glass Lewis may recommend shareholders vote against these proposals in instances where companies have adopted policies whereby they will seek shareholder approval for any cash severance payments exceeding 2.99 times the sum of an executive’s salary and bonus.

- Beginning in 2023, Glass Lewis will raise concerns in its analysis with executive pay programs that subject less than half of an executive’s long-term incentive awards to performance-based vesting conditions. Accordingly, the advisory firm revised the threshold for the minimum percentage of the long-term incentive grant that should be performance-based from 33% to 50%.

Glass Lewis also clarified the following in its 2023 policy guidelines:

- One-Time Awards: If one-time awards are made, companies are expected to include disclosure explaining the determination of the awards’ amounts and structures.

- Front-Loaded Awards: Glass Lewis continues to scrutinize “megagrants,” which companies often provide as front-loaded awards. In situations where a front-loaded award was intended to cover a certain portion of the regular long-term incentive grant for each year during the covered period, Glass Lewis’ analysis of the remaining portion of the regular long-term incentives granted during the period covered by the award will account for the annualized value of the front-loaded portion, and Glass Lewis expects no supplemental grant to be awarded during the vesting period of the front-loaded portion. Additionally, if megagrants have been awarded and generate concerns such as excessive quantum, lack of sufficient performance conditions or excessive dilution, Glass Lewis will generally recommend against the chair of the compensation committee.

- Pay-for-Performance: The new rules do not impact the pay-for-performance methodology and there is no change to the methodology for the 2023 proxy season. However, Glass Lewis may review the disclosure requirements from the new rules in its evaluation of executive pay programs on a qualitative basis.

- Recoupment Provisions: Glass Lewis acknowledged the new regulatory developments related to the SEC’s final rules regarding clawback policies and noted that, during the period between the announcement of the final rules and the effective date of listing requirements, it will continue to raise concerns about companies that maintain clawback policies that only meet the requirements set forth by Section 304 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX). Glass Lewis has indicated that disclosure by a company of early efforts it is taking to meet the standards of the final clawback rules may help mitigate the advisory firm’s concerns.

- Short-Term and Long-Term Incentives: Companies should provide thorough discussion of how significant, material events (that would otherwise be excluded from performance results of selected metrics of incentive programs) were considered in compensation committees’ decisions to exercise discretion or refrain from applying discretion over incentive pay outcomes. Glass Lewis may find the inclusion of this disclosure helpful when it considers concerns about the exercise or absence of committee discretion.

- Company Responsiveness to Say-on-Pay: Companies with low support levels for previous years’ say-on-pay votes should provide robust disclosure, including the rationale for not implementing changes to decisions regarding pay that drove low support, and intentions going forward.

Recommended Next Steps

Overall, proxy advisory firms, institutional investors, the news media, activist shareholders and other stakeholders continue to shine a spotlight on companies’ executive compensation programs, especially amid recent global talent shortages and workers’ rights initiatives, the lingering influence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Biden administration’s economic recovery plans. This year’s proxy season provides an opportunity for companies to clearly disclose the link between pay and performance and efforts to engage with shareholders about executive compensation. As always, these disclosures should explain the company’s rationale for selecting particular performance measures for performance-based pay and the mix of short-term and long-term incentives. Companies should also carefully disclose the rationale for any increases in executive compensation, emphasizing their link to specific individual and company performance.

In the year following a say-on-pay vote, proxy firms conduct a thorough review of companies where say-on-pay approval votes fell below a certain threshold: 70% for ISS and 80% for Glass Lewis. ISS’ FAQ explains that this review involves investigating the breadth, frequency and disclosure of the compensation committee’s stakeholder engagement efforts, disclosure of specific feedback received from investors who voted against the proposal, actions taken to address the low level of support, other recent compensation actions, whether the issues raised were recurring, the company’s ownership structure and whether the proposal’s support level was less than 50%, which should elicit the most robust stakeholder engagement efforts and disclosures.

Looking ahead to 2023, companies that received say-on-pay results below the ISS and Glass Lewis review thresholds should consider enhancing disclosures of their shareholder engagement efforts in 2023 and the specific actions they took to address potential shareholder concerns. Companies that fail to conduct sufficient shareholder engagement efforts and to make these disclosures may receive negative voting recommendations from proxy advisory firms on say-on-pay proposals and compensation committee member reelection.

Recommended actions for such companies include the following:

- Assess results of the most recent say-on-pay vote. As part of this analysis, identify which shareholders were likely the dissenting shareholders and why.

- Engage key company stakeholders by soliciting and documenting their perspectives on the company’s compensation practices. Analyze stakeholder feedback, determine recommended next steps and discuss findings with relevant internal stakeholders, such as the compensation committee and the board of directors.

- Review ISS and Glass Lewis company-specific reports and guidance to determine the reason for their vote recommendations in 2022. Carefully consider how shareholders and proxy advisory firms will react to planned compensation decisions for the remainder of the current fiscal year and recalibrate as necessary. For example, consider compensation for new hires, leadership transitions and any special one-time grants or other arrangements.

- Determine and document which changes will be made to the company’s compensation policies in response to shareholder feedback.

- Disclose specific shareholder engagement efforts and results in the 2023 proxy statement. Such disclosures should include information about the shareholders engaged, such as the number of them, their level of ownership in the company and how the company engaged them. This disclosure should also reflect actions taken in response to shareholder concerns, such as a company’s decision to offer more robust disclosures or to adjust certain compensation practices.

Companies that have not changed their compensation plans or programs in response to major shareholder concerns should consider disclosing (i) a brief description of those concerns, (ii) a statement that the concerns were reviewed and considered and (iii) an explanation of why changes were not made.

Say-on-Golden-Parachute Proposal Results

Say-on-golden-parachute votes historically have received lower support than annual say-on-pay votes, and this trend was even stronger in 2022. Average support for golden parachute proposals dropped from 76% in 2021 to 70% from January 1, 2022, through July 15, 2022.[6] ISS’ negative vote recommendations rose from 37% in 2021 to 47% in 2022. Companies should beware of including single-trigger benefits (i.e., automatic vesting upon a change in control) in their parachute proposals given that stakeholders cite single-trigger vesting as a primary concern, with tax gross-ups and performance awards vesting at maximum value as significant secondary concerns. Companies have historically also cited excessive cash payouts as a concern.

Equity Plan Proposal Results

Equity plans continue to be widely approved, with less than 1% of equity plan proposals at Russell 3000 companies receiving less than a majority vote in 2022 through September 2022.[7] Average support for 2022 equity plan proposals as of September 2022 was 89.3%, which was slightly higher than the 89.1% average support for equity plan proposals observed in September 2021.[8]

Most companies garner strong equity plan proposal support from shareholders, regardless of the say-on-pay results. As of September 2022, Russell 3000 companies with less than 70% approval in say-on-pay votes still received 86% support for equity plan proposals, a 1% increase from the 85% level of support for equity plan proposals observed in 2021.[9]

The threshold number of points to receive a favorable equity plan proposal recommendation from ISS is expected to remain at 57 points for the S&P 500 model, 55 points for the Russell 3000 model and 53 points for all other Equity Plan Scorecard (EPSC) models.[10] ISS did not make changes to the factors, weightings or passing scores for any of the EPSC models.

ISS clarified how it will assess a company’s clawback policy for EPSC purposes, noting that, to receive points, the clawback policy should authorize recovery upon a financial restatement and cover all or most equity-based compensation for all NEOs. A company will not receive credit for a clawback policy that only contains the limited requirements stipulated by the SOX, or if the company discloses that it will establish a clawback policy only after the finalization of applicable rules under the Dodd-Frank Act.

ISS also changed how it considers a company’s burn rate in evaluating stock plans. Currently, ISS uses a three-year adjusted average burn rate, as a percentage of weighted average common shares outstanding, as a measure of the company’s typical annual equity-based grant rate. ISS compares this rate to a benchmark for the company’s industry/index. A company’s three-year adjusted burn rate relative to that benchmark is a factor in the EPSC.[11]

For meetings on or after February 1, 2023, the EPSC burn rate factor will instead use a “Value-Adjusted Burn Rate” (VABR), with benchmarks calculated as the greater of:

- an industry-specific threshold based on three-year burn rates within the company’s GICS group segmented by S&P 500, Russell 3000 index (less the S&P 500) and non-Russell 3000 index; and

- a de minimis threshold established separately for each of the S&P 500, the Russell 3000 index less the S&P 500, and the non-Russell 3000 index.

ISS noted that the VABR seeks to better approximate companies’ equity grant rates through compensation plans by using more accurate measures for the value of equity-based awards. A company’s annual VABR is calculated as follows:

Annual Value – Adjusted Burn Rate = ((# of options * option’s dollar value using a Black-Scholes model) + (# of full-value awards * stock price)) / (weighted average common shares * stock price).

The VABR is expected to replace the existing EPSC burn rate factor beginning with meetings on or after February 1, 2023, with additional information to be provided in ISS’ updated FAQs expected in December 2022.

Other Proxy Advisory Firm Takeaways

ISS’ methodology for evaluating whether nonemployee director (NED) pay is excessive is expected to continue to apply in 2023.

Under such policy, ISS may issue adverse vote recommendations for board members responsible for approving/setting NED pay. Such recommendations could occur where ISS determines there is a recurring pattern (two or more consecutive years) of excessive director pay without disclosure of a compelling rationale for those prior years or other mitigating factors.

Each year, companies should consider whether to make any updates to the compensation benchmarking peers included in ISS’ database. ISS uses these company-selected peers when it determines the peer group it will use for evaluating a company’s compensation programs. This year, ISS will accept these updates through December 5, 2022.[12]

Prepare for 2023 Pay Ratio Disclosures

The year 2023 marks the sixth year that SEC rules require companies to disclose their pay ratios, which compare the annual total compensation of the median company employee to the annual total compensation of the CEO.[13] Companies can prepare for the mandatory pay ratio disclosures by considering the following:

- Can the same median employee be used this year, and, if not, what new factors should be considered when identifying the median employee?

- What else do companies need to know for 2023?

Determining Whether To Use the Same Median Employee

Under Regulation S-K Item 402(u), a company only needs to perform median employee calculations once every three years, unless it had a change in the employee population or compensation arrangements that could significantly affect the pay ratio. This requires companies to assess annually whether their workforce compositions or compensation arrangements have materially changed.

When selecting a median employee for pay ratio disclosures about compensation in fiscal year 2022, companies should consider the following:

- If the company has been using the same median employee for three years, the company will need to perform median employee calculations for fiscal year 2022.

- Other companies that were originally planning to feature the same median employee as last year should not do so if their employee populations or employee compensation arrangements significantly changed in the past year.

When selecting a median employee for pay ratio disclosures regarding fiscal year 2022, companies should carefully consider how to incorporate furloughed employees, if applicable.[14]

Additionally, companies should consider how headcount changes may impact their ability to exclude certain non-U.S. employees from their pay ratio calculation under the commonly relied upon de minimis exception in Item 402(u)(4)(ii). Therefore, companies should evaluate whether non-U.S. employees in the aggregate, and by jurisdiction, newly constitute or no longer constitute more than 5% of the company’s total employees.

- The de minimis exception generally allows a company to exclude non-U.S. employees when identifying its median employee if excluded non-U.S. employees constitute 5% or less of its workforce.

- If a company’s non-U.S. employees account for 5% or less of its total employees, the company may either exclude all non-U.S. employees or include all non-U.S. employees.

- Alternatively, if over 5% of a company’s total employees are non-U.S. employees, the company may exclude up to 5% of its total employees who are non-U.S. employees; provided that the company excludes all non-U.S. employees in a particular jurisdiction if it excludes any employees in that jurisdiction, and employees excluded under Item 402(u)’s data privacy exception count toward this limit.

- Non-U.S. jurisdictions with employees that exceed 5% of a company’s total employees may not be excluded from the pay ratio calculation under the de minimis exception, although they may be permitted to be excluded under the data privacy exception.

Even if a company uses the same median employee in its proxy statement filed in 2023 as the company used in 2022, it must disclose that it is using the same median employee and briefly describe the basis for its reasonable belief that no change occurred that would significantly affect the pay ratio.

To determine whether a material change occurred, companies should continue to evaluate the following factors:

- How has workforce composition evolved over the past year?

- Review hiring, retention and promotion rates.

- Consider the applicability of exceptions under the pay ratio rules:

- Determine whether to incorporate employees from recent acquisitions or business combinations into the consistently applied compensation measure (CACM). For example, for the fiscal year in which a business combination or acquisition becomes effective, a company may exclude individuals that become its employees as the result of the business combination or acquisition, as long as the company discloses the approximate number of employees it is omitting and identifies the acquired business it is excluding.

- Determine whether the de minimis exception applies within the context of the company’s 2022 workforce composition. As described above, under this exception, non-U.S. employees may be disregarded if the excluded employees account for less than 5% of the company’s total employees or if a country’s data privacy laws make a company’s reasonable efforts insufficient to comply with Item 402(u).

- Analyze how the workforce used for the CACM is distributed across the pay scale and how the distribution has changed since last year.

- How have compensation policies changed in the past year compared to the workforce composition? For example, an across-the-board bonus that benefits all employees may not materially change the pay ratio, while new special commission pay limited to a company’s sales team would do so.

- Have the median employee’s circumstances changed since last year? Consider changes to the employee’s title and job responsibilities alongside any changes to the structure and amount of the employee’s compensation, factoring in the company’s broader workforce composition. Additionally, if the median employee was terminated, companies must identify a new median employee.

Although the SEC provides companies with substantial flexibility in calculating their pay ratios, to satisfy the SEC staff and engage with investors, employees and other stakeholders, companies should continue to diligently document and disclose their pay ratio methodology, analyses and rationale.

Confirm Timing of the Next Say-on Frequency Vote

The SEC requires reporting companies to conduct a shareholder vote on the frequency of the say-on-pay vote every six years, known as “say-on-frequency” vote. The first year that the say-on-frequency vote was required was in 2011. Because many companies first provided shareholders the opportunity to cast a say-on-frequency vote in 2011, many included the nonbinding advisory vote again in 2017 proxy statements and anticipate doing so again in 2023. The 2023 proxy season will mark the third time such votes are required.

Although the say-on-frequency vote is nonbinding and advisory in nature, the proxy cards must provide shareholders the option to vote for one, two or three-year periods between say-on-pay votes or to abstain from voting. The company should also state on the cards the current voting frequency, that the shareholder vote is advisory in nature and nonbinding, and when the next scheduled say-on-pay vote will occur. Additionally, companies should also note that they are required to conduct a say-on-frequency vote every six years, even if a company is already conducting its say-on-pay vote annually and intends to continue such practice.

Companies that qualify under the SEC’s proxy rules as “smaller reporting companies” were not required to hold their first say-on-frequency vote until 2013, which means the third say-on-frequency vote for such companies that held say-on-frequency votes last in 2019 will be required in 2025. Emerging growth companies are exempt from the say-on-pay and say-on-frequency votes.

Annual Frequency Remains Most Common

At the overwhelming majority of companies, shareholders voted in favor of an annual say-on-pay vote, and that frequency remains by far the most common. Data from the last two say-on-frequency votes (i.e., 2011 and 2017) from Russell 3000 companies shows that 81% of companies adopted an annual say-on-pay frequency in 2011, whereas 91% of companies adopted an annual say-on-pay frequency in 2017.[15] Companies slightly favored triennial versus biennial frequency with 18% of companies adopting triennial say-on-pay frequency in 2011 and 8% of companies adopting triennial frequency in 2017. It is expected that companies, shareholders and institutional investors will continue to favor annual say-on-pay votes in 2023.

Form 8-K Filing Requirement

Within four days following the annual meeting of the shareholders, a company must file a Form 8-K disclosing the results of the say-on-frequency vote. The disclosure must state the number of votes cast for each of “one year,” “two years,” and “three years,” as well as the number of abstentions. Although the say-on-frequency vote is advisory in nature, companies must also disclose the decision of the board of directors regarding the frequency of future say-on-pay votes in a Form 8-K filing. The SEC permits a company up to 150 calendar days after the annual shareholder meeting (but no later than 60 days prior to the deadline for shareholder proposals for the next year) to decide and disclose its decision on future say-on-frequency votes.

Evaluate Hart Scott-Rodino Act Implications on Executive Compensation

Officers and directors who hold at least $101 million in voting securities in their companies should consider the need to make Hart-Scott-Rodino (HSR) filings whenever they increase their holdings through an acquisition of voting securities.[16] A company’s annual preparation of its beneficial ownership table provides a regular opportunity to assess whether any of its officers or directors may be approaching an HSR filing threshold, in which case consulting HSR counsel is highly recommended. Importantly, HSR counsel also can advise when exemptions are available to obviate the need to file notifications.

An acquisition is considered to occur only when the officer or director obtains beneficial ownership of the shares. Therefore, acquisitions may include, without limitation:

- grants of fully vested shares as a component of compensation;

- the vesting or settlement of restricted stock units and performance-based restricted stock units;

- the exercise of stock options;

- open market purchases of shares; and

- the conversion of convertible nonvoting securities into voting shares.

However, an officer or director would not be deemed to “acquire” shares underlying restricted stock units or performance-based restricted stock units that have not vested or shares underlying stock options that have not yet been exercised.

Generally, an “acquisition” can trigger a filing obligation.[17] For example, a filing requirement is not triggered solely by an increase in the value of an officer’s holdings from $100 million to $105 million as a result of share price appreciation. However, if such officer subsequently wanted to exercise a stock option, an HSR obligation could be triggered.

The need for a filing is triggered whenever — after the acquisition of voting securities — an officer or director’s holdings of voting securities in the company exceed an HSR filing threshold (the lowest of which is currently $101 million). Current holdings plus the proposed acquisition are considered to determine whether the threshold has been met.

Higher voting securities thresholds triggering additional HSR filings exist as well, with the next two currently fixed at $202 million and $1.0098 billion.[18]

If a filing is required, the individual would need to make an HSR filing and wait 30 days before completing the triggering acquisition. The filer has one year from clearance to cross the applicable acquisition threshold and may make additional acquisitions for five years thereafter with no further HSR filings, provided that the filer does not cross the next HSR threshold above the level for which the notification was filed.

The Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice have historically followed an informal “one free bite at the apple” enforcement practice when it comes to certain missed HSR filings, meaning that, if an officer or director inadvertently failed to make a required HSR filing, that person should notify the agencies and submit a corrective filing detailing his or her previous acquisitions and how he or she plans to meet filing obligations in the future. This one “free bite” may address all prior missed filings that occurred before the corrective filing.

However, the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice have been known to pursue enforcement actions and may impose material civil penalties of up to $46,517 per day[19] for each day of noncompliance if an executive officer or director subsequently fails to make a required HSR filing, even if such failure was truly inadvertent.[20] Therefore, officers and directors who have made corrective filings should be especially vigilant and consult HSR counsel regularly before a potential subsequent “acquisition” event is expected to occur.

Prepare for Final Clawback Rules Under Dodd-Frank

On October 26, 2022, the SEC adopted long-awaited final rules implementing the incentive-based compensation recovery (clawback) provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act.[21] The final rules direct the stock exchanges to establish listing standards requiring listed companies to develop and implement policies providing for the recovery of erroneously awarded incentive-based compensation received by current or former executive officers and to satisfy related disclosure obligations.

The final rules largely track the proposed rules originally released in July of 2015, although (as described below) there are some important differences to understand, especially when evaluating existing clawback policies that were designed to comply with the proposed rules. For example, even some “little r” restatements that did not involve a material misstatement in past years may trigger a clawback under the final rules. The new rules also require more detailed disclosures about how a company’s policy was implemented in the most recent fiscal period.

Clawback Policy Requirements: Listed companies will be required to adopt a clawback policy providing for recovery of incentive-based compensation erroneously received by current or former executive officers during the three completed fiscal years immediately preceding the year in which the company is required to prepare an accounting restatement due to material noncompliance with financial reporting requirements. Erroneous payments must be recovered even if there was no misconduct or failure of oversight on the part an individual executive officer.

Listed companies will be required to (i) file their written clawback policies as exhibits to their annual reports, (ii) indicate by checkboxes on the cover pages of their annual reports whether the financial statements included in the filings reflect a correction of an error to previously issued financial statements and whether any of those error corrections are restatements requiring a recovery analysis of incentive-based compensation under their clawback policies and (iii) disclose how they have applied their clawback policies during or after the last completed fiscal year.

Under the new rules, a company could be subject to delisting if it does not adopt a clawback policy that complies with the applicable listing standard, disclose the clawback policy and any application of the policy in accordance with SEC rules or enforce the clawback policy’s recovery provisions.

Issuers Subject to the Final Rules: Almost all listed companies (including foreign private issuers, controlled companies, smaller reporting companies and emerging growth companies, but excluding certain registered investment companies) are subject to the final rules. While many commenters raised concerns about the potential difficulties that the final rules would impose on foreign private issuers, the SEC was unpersuaded. The only exempted listed companies under the final rules are issuers of security futures products, standardized options, unit investment trust securities and certain registered investment company securities.

Covered Executive Officers: The final rules adopt the same definition of “executive officers” used to determine a listed company’s officers under Exchange Act Rule 16a-1 (for domestic issuers, the “Section 16 officers”). These executive officers, including former executive officers who are no longer serving at the time the clawback is required, are subject to the clawback requirements without regard to any individual knowledge or responsibility related to the restatement or the mistaken payments.

However, in a change from the proposed rules, the final rules do not require recovery of incentive-based compensation (i) where the compensation was received by a person before beginning service as an executive officer or (ii) if that person did not serve as an executive officer at any time during the three-year lookback period to which the clawback rules apply.

Triggering Events: A triggering event will commence application of the clawback policy before an accounting restatement is actually filed. The three-year look-back period starts on the earlier of (i) the date the company’s board of directors, committee and/or management concludes (or reasonably should have concluded) that a restatement is required or (ii) the date a regulator, court or other legally authorized entity directs the company to restate previously issued financial statements.

Covered Accounting Restatements: The final rules require that both “Big R” and “little r” accounting restatements trigger the clawback policy. A “Big R” restatement occurs when a company is required to prepare an accounting restatement that corrects an error in previously issued financial statements that is material to those previously issued financial statements. A “Big R” restatement requires the company to file an Item 4.02 Form 8-K and to amend its filings promptly to restate the previously issued financial statements. By contrast, a “little r” restatement corrects an error that would result in a material misstatement if the error were not corrected in the current period or was corrected in the current period and generally does not require Form 8-K filing.

The SEC provides the following example of a “little r” restatement: Assume that an improper expense accrual (such as an overstated liability) has accumulated over five years at $20 per year. Upon identification of the error in year five, the company evaluated the misstatement as being immaterial to the financial statements in years one through four (at only $20 per year). To correct the overstated liability in year five, a $100 credit to the statement of comprehensive income would be necessary, and $80 of this credit would relate to the previously issued financial statements for years one through four.

During the preparation of its annual financial statements for year five, the company determines that, although a $20 annual misstatement of expense would not be material to year five, the adjustment to correct the $80 cumulative error from previously issued financial statements would be material to comprehensive income for year five. Accordingly, instead of correcting the full $100 error in year five (which would result in a material misstatement if the error was corrected in the current period) or not correcting the error at all (which would result in a material misstatement if the error was not corrected in the current period), the company must correct the financial statements for years one through four to the extent they appear in the current filing for year five.

The SEC noted in the adopting release that its estimates reflect that “little r” restatements may be roughly three times as common as “Big R” restatements. The 2015 proposed rules provided that only a “Big R” restatement triggered a clawback, and many companies that proactively adopted clawback policies based on the proposed rules will need to incorporate into their existing policies “little r” restatements as triggering events to apply clawback protocols.

Recovery of Erroneously Awarded Incentive-Based Compensation: The final rules require that clawback policies provide for recovery of “incentive-based compensation,” defined as “any compensation that is granted, earned, or vested based wholly or in part upon the attainment of a financial reporting measure.” “Financial reporting measures” may include both GAAP and non-GAAP financial measures, including stock price and TSR metrics. Awards based solely on continued employment do not need to be subject to clawback under the policy.

The amount of compensation subject to recovery (“erroneously awarded”) is the excess of:

- the incentive-based compensation actually paid during the fiscal period when the applicable financial reporting measure is attained; over

- the amount that would have been received had the financial statements been correct in the first instance.

Examples of compensation that do not meet the definition of “incentive-based compensation” for purposes of the final rules include, but are not limited to:

- salaries;

- bonuses paid solely at the discretion of the compensation committee or the board of directors that are not paid from a “bonus pool” that is determined by achieving a financial reporting measure;

- bonuses paid solely upon satisfying one or more subjective standards and/or completion of a specified employment period;

- nonequity incentive plan awards earned solely upon satisfying one or more strategic measures (e.g., consummating a merger or divestiture) or operational measures (e.g., opening a specified number of stores, completing a project, increasing market share); and

- equity awards for which the grant is not contingent upon achieving any financial reporting measure and vesting is contingent solely upon completion of a specified employment period and/or attaining one or more nonfinancial reporting measures (e.g., discretionary grants of time-vesting restricted stock, restricted stock units or stock options).

When Incentive-Based Compensation Is “Received”: Incentive-based compensation will be deemed “received” for purposes of the clawback policy requirements in the fiscal period during which the financial reporting measure is attained, even if the payment or grant occurs after the end of that period. The date the compensation is “received” depends upon the terms of the award.

For example:

- If the grant of an award is based on satisfaction of a financial reporting measure, the award will be deemed received in the fiscal period when that measure was satisfied.

- A nonequity incentive plan award will be deemed received in the fiscal year that the executive officer earns the award based on satisfaction of the relevant financial reporting measure, rather than a subsequent date on which the award was paid.

- A cash award earned upon satisfaction of a financial reporting measure will be deemed received in the fiscal period when that measure is satisfied.

Exceptions to Recovery: The new listing standards provide for limited exceptions to the company’s obligation to enforce the application of the clawback policy due to impracticability of such recovery. These exceptions are only available where:

- pursuing such recovery would be impracticable because the direct expense paid to a third party to assist in enforcing the policy would exceed the recoverable amounts and the issuer has (a) made a reasonable attempt to recover such amounts and (b) provided documentation of such attempts to recover to that company’s applicable listing exchange;

- pursuing such recovery would violate the listed company’s home country laws and the company provides to the exchange an opinion of counsel to that effect; or

- recovery would likely cause an otherwise tax-qualified retirement plan, under which benefits are broadly available to employees of the registrant, to fail to meet the requirements of the Internal Revenue Code.

Restrictions on Indemnification and Insurance: The new rules prohibit listed companies from indemnifying or reimbursing any current or former executive officer against the recovery of erroneously awarded compensation. The rules also prohibit companies from paying the premiums on an insurance policy that would cover an executive officer’s potential clawback obligations.

New Disclosure Requirements: The final rules include new disclosure requirements regarding how the clawback policy is implemented, during or following the end of the most recently completed fiscal year, including a requirement to provide:

- the date on which the listed issuer was required to prepare an accounting restatement and the aggregate dollar amount of erroneously awarded incentive-based compensation attributable to such accounting restatement;

- the aggregate amount of incentive-based compensation that was erroneously awarded to all current and former NEOs that remains outstanding at the end of the last completed fiscal year;

- any outstanding amounts due from any current or former executive officer for 180 days or more, separately identified for each named executive officer (or, if the amount of such erroneously awarded incentive compensation has not yet been determined as of the time of the report, disclosure of this fact and an explanation of the reasons why); and

- if recovery would be impracticable, for each current and former named executive officer and for all other current and former executive officers as a group, the amount of recovery forgone and a brief description of the reason the listed registrant decided in each case not to pursue recovery.

Such disclosure will be required as part of the executive compensation disclosure provisions in new Item 402(w) of Regulation S-K (or analogous disclosure provisions in the forms applicable to foreign private issuers and listed funds). Note that, if an amount is properly determined to be not recoverable due to impracticality, such amount will not be considered to be outstanding at the last fiscal year for purposes of the disclosure requirements described above.

Companies must also incorporate any recoupment of compensation into the amounts shown for the year of recoupment in the Summary Compensation Table by subtracting the amount recovered from the amounts reported in the Summary Compensation Table for that year and quantify the amount recovered in a footnote.

New Exhibit Filing; XBRL: The new rules will require companies to file their clawback policies as exhibits to the annual reports on Form 10-K, 20-F or 40-F. The new disclosure on the cover page of the Form 10-K, 20-F or 40-F, as applicable, and Item 402(w) with respect to domestic companies, must be tagged in interactive block text tag format using eXtensible Business Reporting Language.

Effects on Existing Clawback Rules: CEOs and CFOs remain subject to the clawback provisions of SOX, which provide that if a company is required to prepare an accounting restatement because of “misconduct,” the CEO and CFO are required to reimburse the company for any incentive or equity-based compensation and profits from selling company securities received during the year following issuance of the inaccurate financial statements. To the extent that the Dodd-Frank Act clawback policy and SOX cover the same recoverable compensation, the CEO or CFO would not be subject to duplicative reimbursement. Recovery under the new rules will not preclude recovery under SOX to the extent any applicable amounts have not been reimbursed to the issuer.

When the New Rules Take Effect: The SEC’s final rules were published in the Federal Register on November 28, 2022, and will become effective on January 27, 2023. The stock exchanges have up to 90 days after publication to propose new listing standards, and those only need to become effective within one year following the publication date.

Following the effective date of the new listing standards, listed companies will have 60 days to adopt the required clawback policy. A listed company must recover all erroneously awarded incentive-based compensation that is received on or after the effective date of the applicable listing standard.

What Companies Should Do Now: Listed companies that will be subject to the new requirements should consider the following actions:

- Review existing clawback policies to consider what changes may be required, particularly given the additional requirements imposed since the 2015 proposed regulations. Note, however, that companies may want to wait for the stock exchanges to release their implementing listing standards (which could be broader than the SEC requirements) before actually adopting or amending clawback policies to comply with the new rules.

- Start considering which aspects of the compensation plan to review and possibly supplement in light of the clawback mandate.

- Review executive officer determinations in light of the new significance of this designation.

Monitor Form S-8 Share Issuance Capacity

Companies should be mindful to monitor the number of shares available for sale under their Form(s) S-8. As discussed below, the impact of share recycling provisions found in many equity compensation plans can obscure the number of shares available for sale under a Form S-8.

When companies register on Form S-8 the sale of securities under an equity compensation plan, a fixed number of securities is registered for sale. Other than automatic adjustments tied to stock splits, dividends and certain anti-dilution provisions, that fixed number of registered securities cannot be increased without filing a new Form S-8. For purposes of keeping track of the finite capacity available under an effective Form S-8, each share associated with a compensatory award should be deducted from the total number of shares available for issuance under the Form S-8 at the time the sale of the securities occurs. In the case of full value awards such as restricted stock, restricted stock units and performance stock units, the sale occurs at grant, whereas in the case of employee stock options and stock appreciation rights, the sale occurs upon exercise of the subject award. Shares that are deemed sold must be deducted from the available capacity at the time of sale. The shares cannot be added back to the total number of shares available for issuance under the Form S-8 even if those shares are later forfeited back to the company by the grantee and revert to the equity incentive plan.

Impact of Share Recycling

Many equity incentive plans allow for share recycling under certain conditions so that shares subject to awards granted under the plan that are subsequently forfeited or surrendered revert to and replenish the share reserve available under the plan. These share recycling provisions can result in a discrepancy between the number of registered securities available for sale under the Form S-8 and the number of authorized securities available under the subject employee compensation plan.

Recommended Steps

Companies should consider separately tracking the number of registered securities available for sale under the Form S-8 and the number of authorized securities available under the subject employee compensation plan to ensure that a company does not inadvertently grant equity awards under its equity compensation plan when the Form S-8 no longer has a sufficient number of registered shares available for issuance.

Endnotes

1See Semler Brossy’s report “2022 Say on Pay & Proxy Results” (September 29, 2022). See also Semler Brossy’s report “2021 Say on Pay & Proxy Results” (January 27, 2022). Unless otherwise noted, Semler Brossy’s report is the source of pay ratio, say-on-pay and equity plan proposal statistics in this guide.(go back)

2See Semler Brossy’s report “2022 Say on Pay & Proxy Results” (September 29, 2022).(go back)

3See ISS’ FAQ “United States Compensation Policies” (December 17, 2021).(go back)

4For more information, see ISS’ Pay-for-Performance Mechanics white paper.(go back)

5See Glass Lewis’ “2023 Policy Guidelines — United States” (November 18, 2022) and “2023 Policy Guidelines — ESG Initiatives” (November 18, 2022).(go back)

6See Willis Towers Watson’s report “U.S. Executive Pay Votes — 2022 Proxy Season Review” (October 2022).(go back)

7See Semler Brossy’s report “2022 Say on Pay & Proxy Results” (September 29, 2022). See also Semler Brossy’s report “2021 Say on Pay & Proxy Results” (January 27, 2022).(go back)

8See Semler Brossy’s report “2022 Say on Pay & Proxy Results” (September 29, 2022).(go back)

9See id(go back)

10See ISS’ FAQ “United States Equity Compensation Plans” (December 17, 2021).(go back)

11ISS lists the burn rate benchmarks applicable for meetings on or after February 1, 2022, in the Appendix section of its FAQ; see id.(go back)

12See ISS’ “Company Peer Group Feedback” (2022).(go back)

13Emerging growth companies, smaller reporting companies and foreign private issuers are exempt from the pay ratio disclosure requirement. Transition periods are also available for newly public companies.(go back)

14For information on how to incorporate furloughed employees into pay ratio calculations, see the section titled “Incorporate Lessons Learned From the 2020 Say-on-Pay Votes and Compensation Disclosures and Prepare for 2021 Pay Ratio Disclosures — Prepare for 2021 Pay Ratio Disclosures” in our December 14, 2020, publication “Matters To Consider for the 2021 Annual Meeting and Reporting Season.”(go back)

15See Willis Towers Watson’s “Executive Compensation Bulletin: Preference for Annual Say-on-Pay Votes Grows — for Now” (August 2017).(go back)

16The HSR Act establishes a set of notification thresholds that are adjusted annually based on changes to the gross national product. The initial threshold for 2022 is $101 million and new thresholds will be established in the first quarter of 2023.(go back)

17Note that an HSR reporting obligation also can be triggered by an increase in one’s voting power (i.e., holding or acquiring voting securities that provide more than one vote per share). HSR counsel can assist with analyzing the impact on the filing requirements.(go back)

18See the Federal Trade Commission’s “HSR Threshold Adjustments and Reportability for 2022” (February 11, 2022)(go back)

19The Federal Trade Commission is required by the Federal Civil Penalties Inflation Adjustment Act, as amended, to adjust the HSR civil penalty amount for inflation in January of each year based on the percentage change in the consumer price index. The maximum civil penalty for an HSR violation in 2022 is $46,517 per day and the new maximum will be established in January 2023.(go back)

20See the Federal Trade Commission’s press releases “FTC Fines Capital One CEO Richard Fairbank for Repeatedly Violating Antitrust Laws” (September 2, 2021) and “FTC Fines Clarence L. Werner, Founder of the Truckload Carrier Werner Enterprises, Inc. for Repeatedly Violating Antitrust Laws” (December 22, 2021).(go back)

21See the SEC’s final rule “Listing Standards for Recovery of Erroneously Awarded Compensation” (October 26, 2022) and press release “SEC Adopts Compensation Recovery Listing Standards and Disclosure Rules” (October 26, 2022).(go back)

Print

Print