Click to Download: Transcending Fair Market Value

Transcending Fair Market Value

“Beauty is in the eyes of the beholder.”

Margaret Wolfe Hungerford (née Hamilton), who authored many books, often under the pseudonym of ‘The Duchess’.

When I think about value, I (like most in my profession) think first about fair market value (“FMV”). The classic definition of fair market value is:

The price at which the property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller when the former is not under any compulsion to buy and the latter is not under any compulsion to sell, both parties having reasonable knowledge of relevant facts.[1]

But the concept of value is complex. It transcends FMV.

At its core, value is the measure of worth for a good or service expressed in monetary terms. However, since the worth of a good or service varies from individual to individual and under different settings, there are many distinct types of value with distinct definitions (e.g., intrinsic value, fair value, fair market value).

Further, a common misconception is to think of value only in terms of the monetary benefits derived from the good or service, but it is really much more. The value of a good or service also depends on all of the qualitative and intangible benefits that may not directly lead to a monetary benefit or may even have no monetary benefit at all.

If I buy a rare sports car for, say, $100,000, and I get to view it every time I walk into the garage, what is its value? Arguably, its value to each buyer is $100,000 or more, or they would not buy it. Its price is $100,000, and its FMV is $100,000 (assuming it was bought at arms-length in an active market), but I may have agreed to pay much more. And what is the value of the pleasure I derive from the car, the drive, the fun, and its aesthetic beauty? The psychological gratification to show it to and discuss it with friends? How do you measure that?

Similarly, what about a painting on the wall? It may go up or down in value, but you get to look at it every day. Not too many people frame stock certificates, or bank statements.

This paper attempts to explain and distinguish between various valuation concepts, such as price, fair market value, fair value, liquidation value, intrinsic value, financial value versus strategic value, monetary versus economic value, emotional and psychic value, among others. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) value is relatively new, and gaining acceptance in corporate America. Hedonic value has various meanings and uses but is usually thought of as the immediate emotional gratification (perhaps a cause for impulse buying), as contrasted to utilitarian value[2] (e.g., cars used exclusively for transportation).

Many people have heard of the cost, market, and income approaches to valuation, and these various approaches and hybrids can sometimes be applied to determining the different value standards mentioned above. But while valuation (the process of putting a value on something) is part science and part art, there are well accepted techniques, methodologies, and theories that should be adhered to. Valuation necessarily requires an understanding and deep insight into accounting, economics, and finance. Now, statistical analysis, behavioral finance,[3] and cultural economics[4] are playing a more frequent role in valuation.

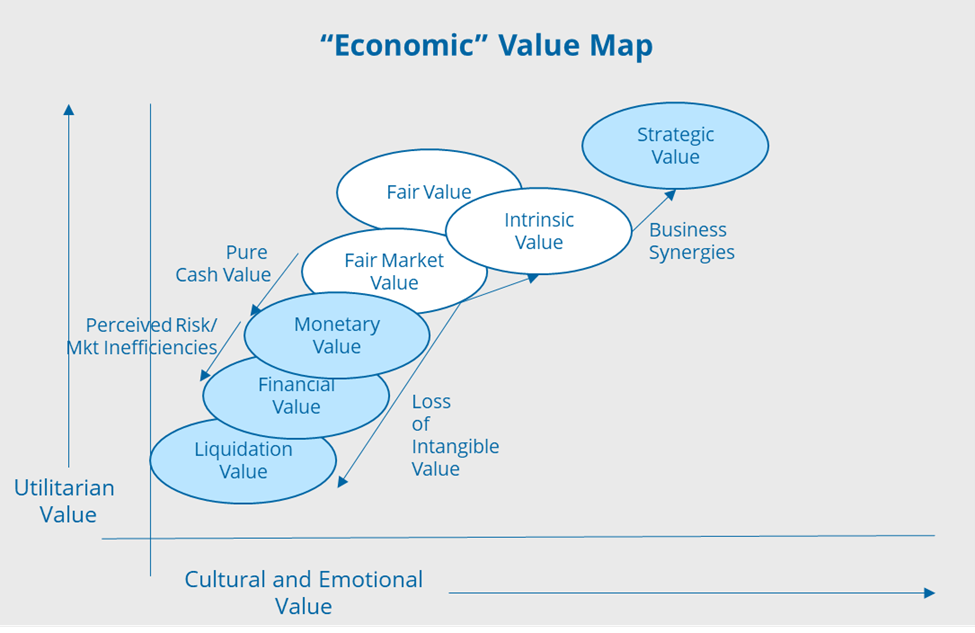

Fair Market Value

As the most common standard of value, it may be easiest to describe other value standards graphically as interrelationships and deviations from fair market value. The plot below depicts utilitarian value against what I call cultural and emotional value. Fair market value is generally high on the utilitarian scale (it represents the cash-equivalent price a buyer is willing to pay) and relatively low in cultural and emotional value.

Intrinsic and Fair Value

Intrinsic value can be related to psychic or emotional value but normally is thought of as the cash equivalent value (on a present value basis) to a specific owner. That owner is usually the current owner and the value usually represents the value of the future cash flow, including the proceeds from a future sale. Since taxes can be quite different in a sale (capital gains) versus income, normally an after-tax analysis is required to understand the scenario that may be more advantageous; hold versus sell. But, once again, the owner may derive “satisfaction” and other rewards from being the owner/boss. The tradeoff may be more than money, especially since the owner is incurring more risk.

I have placed the intrinsic value bubble above and to the right of FMV since the owner may have more time value (can realize income for more years and sell at a later date), all the while deriving more emotional or psychic benefits.

Fair value, like intrinsic value can certainly overlay (in the range of possible values) FMV and is normally calculated without regard to discounts associated with the lack of control and marketability. The fair value of public stock is normally the same as its FMV. In the case of closely held companies, the two can be markedly different because minority shareholders in private companies usually cannot sell their stock easily or control operations.

Liquidation, Monetary, Financial, and Strategic Value

The liquation value is simply the FMV without the intangible assets of the business unless certain intangibles such as patents can be separately sold/licensed and utilized by another firm. The monetary value is just what it says, pure cash value without regard to any psychic benefits.

To the typical private equity group (“PEG”), financial value rules – buy low and sell high. It is all about cash-on-cash return. A PEG usually requires higher returns (in part, to compensate for additional perceived risk since a seller will always know more than a buyer); therefore, the financial value is less than the expected monetary value (until they are a seller, of course). PEG buyers also often look for market inefficiencies to achieve superior returns. More often private equity buyers compete with strategic buyers (most often corporate buyers) in that revenue and cost savings synergies accelerate their value creation.

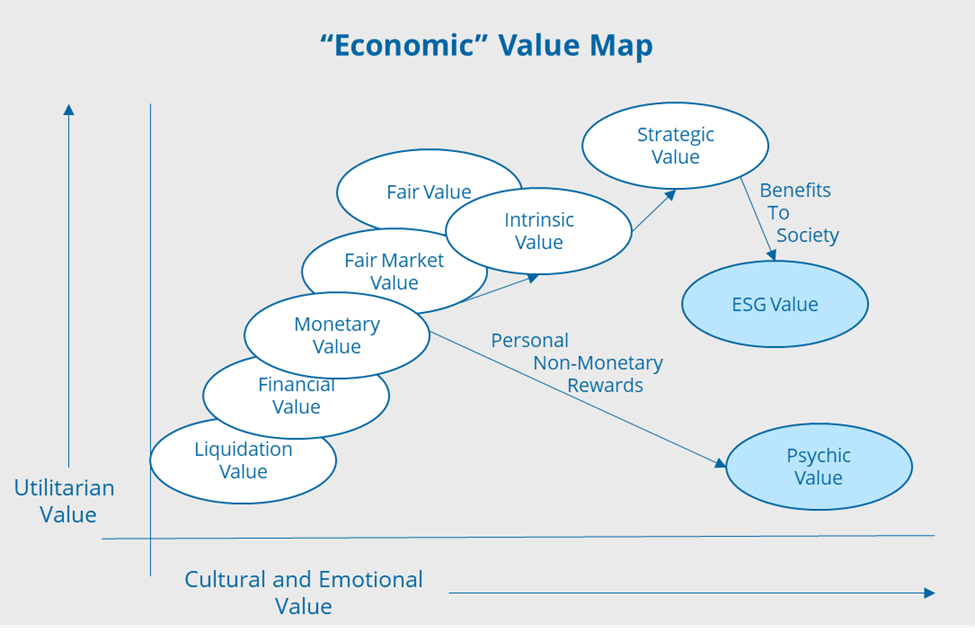

ESG and Psychic Value

Academic research has shown that incorporating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations into the valuation of a company has (on average) a 9.8% increase on value.[5] While adopting ESG can manifest into higher cash flows and/or growth for a company, we often see a significant portion of ESG value coming in the form of a reduction in the required rate of return (i.e., the cost of capital).[6],[7] In fact, we see this reduction in the required rate of return bear out in the realized rate of return (i.e., the stocks of ESG companies have lower actual rates of return).[8],[9] This begs the question: why do investors have a lower required rate of return for ESG companies?

It turns out that investors are willing to accept a lower rate of return when investing in ESG companies because of the non-monetary benefits they receive from investing in ESG companies. The amount of additional benefit is buyer-specific, and while certainly related to the market price (FMV), the economic cost (which can be measured by how much return the investor is sacrificing for the given level of risk), plus the price paid would represent the total price the investor has in effect “paid.” So, in my plot, I have placed ESG value to the right of FMV (higher cultural and emotional value) and below FMV (less utilitarian value).

Likewise, the sports car buyer or art collector is in a similar mode, getting to talk about the purchase, combined with the viewing pleasure (an additional attribute only relevant to physical assets).

Sports franchise investments often have similar characteristics. Many do not make money, or at least not a fair return on investment. In the case of certain franchises, though, the name recognition for the owner may lead to other opportunities that result in additional monetary value; or the owner may just derive a “psychic return” from the pleasure of being the owner of something so public and exclusive.

In fact, psychic return is a term of art in cultural economics. It turns out that the actual returns on certain assets such as art are not commensurate with the risk inherent in holding the art (measured by their volatility over time in price). It is this psychic return, the emotional gratification that comes from the ability to display, discuss (or brag), and view the art, which makes up for the missing return.

The sports car, fine art, and sports franchise examples may fall even farther than ESG value on the utilitarian axis, but to its right on the “psychic” scale.

On a more human and altruistic level, people all over the world work for less pay than their “opportunity cost” to take jobs that are psychologically rewarding. Once I was asked to determine the economic loss associated with an injured, and scared, fashion model. I recognized she lost more than her income; she lost the emotional rewards associated with being a model. So, I conducted a survey to determine the amount of additional income it would take for the typical model to take a different job that she was qualified for, such as executive assistant (a job that today is almost obsolete) and added that to her lost income.

The Greatest of all Time (“GOAT”) Value

A paper on transcending value would not be complete without mention of the GOAT (aka, Tom Brady). While Michael Jordan has arguably the greatest brand value in the history of sports, Tom Brady could compete for that valuation, should he want to.

Let us examine what has led to his value; Wins and Super Bowls! And what has he done (other than be a great QB) to get there? He has taken less than market salary and restructured his contract several times to surround himself by more expensive and presumably better teammates so that he can win. So, he has derived huge psychic value at the expense of monetary value that could translate to enormous economic value, assuming he decides to fully monetize his success and fame.

I hope this short paper gets you thinking about the next major purchase, be it a business, a depreciable asset (like most cars), a perishable asset (such as a trip, although the psychic value created through memories can be high), or just something you have just always wanted. In any event, it might give you some arguments with your significant other why you absolutely, positively need that sports car!

Questions and comments may be directed to Martin Hanan, CFA at 817-481-4900 or mhanan@valuescopeinc.com.

Marty Hanan is the founder and President of ValueScope, Inc., a valuation and financial advisory firm that specializes in valuing assets and businesses and in helping owners and executives in business transactions and estate planning. Mr. Hanan is a Chartered Financial Analyst and has a B.S. Electrical Engineering from the University of Illinois and an MBA from Loyola University of Chicago.

[1] Revenue Ruling 59-60, 1959-1 C.B. 237.

[2] Babin, B., Darden, W., & Griffin, M. (1994). Work and/or Fun: Measuring Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Value. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(4), 644-656. Retrieved March 26, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2489765.

[3] “Behavioral finance studies how people actually behave in a financial setting. Specifically, it is the study of how psychology affects financial decisions, corporations, and the financial markets.” Nofsinger, J. R. (2002). The psychology of investing. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

[4] “…cultural economics is defined as the application of economic theory to the cultural sector…” Towse,Ruth, 2019. “A Textbook of Cultural Economics,” Cambridge Books, Cambridge University Press, number 9781108421683.

[5] Willem Schramade (2016) Integrating ESG into valuation models and investment decisions: the value-driver adjustment approach, Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 6:2, 95-111, DOI: 10.1080/20430795.2016.1176425

[6] Lasse Heje Pedersen, Shaun Fitzgibbons, Lukasz Pomorski, Responsible investing: The ESG-efficient frontier, Journal of Financial Economics, 2020, ISSN 0304-405X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2020.11.001.

[7] Guido Giese, Linda-Eling Lee, Dimitris Melas, Zoltán Nagy and Laura Nishikawa, The Journal of Portfolio Management, July 2019, 45 (5) 69-83; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3905/jpm.2019.45.5.069

[8] Morningstar shows that portfolios of companies with lower ESG ratings outperforms portfolios with of companies with higher ESG ratings. https://www.morningstar.com/insights/2020/02/19/esg-companies

[9] Lasse et al show that the lower returns are predominately from the environmental (E) and social (S) factors. Higher ratings for the corporate governance (G) factor have been shown to result in superior returns.

Marty Hanan is the founder and President of ValueScope, Inc., a valuation and financial advisory firm that specializes in valuing assets and businesses and in helping business owners in business transactions and estate planning. Mr. Hanan is a Chartered Financial Analyst and has a B.S. Electrical Engineering from the University of Illinois and an MBA from Loyola University of Chicago.

The information presented here is not nor should it be treated as investment, financial, or tax advice and is not intended to be used to make investment decisions.

If you liked this blog you may enjoy reading some of our other blogs here.