Dean Kingsley is a Principal and Matt Solomon is a Senior Manager at Deloitte & Touche LLP. Kristen Jaconi is an Associate Professor of the Practice in Accounting and Executive Director at Peter Arkley Institute for Risk Management at the USC Marshall School of Business. This post is based on their recent Deloitte report.

Many S&P 500 companies disclosed they have not experienced past material cybersecurity incidents; however, geopolitics and remote work have heightened cybersecurity risk.

The past 12 months have continued to demonstrate significant volatility and uncertainty in the business environment and broader society, including tectonic shifts in disruptive technologies like Generative artificial intelligence (AI), continued economic upheaval, systemic banking risks, complex domestic and global politics, rising workforce activism, ongoing regulatory reform, devastating natural disasters, and the long-term effects of the pandemic. Public companies continue to be challenged to create and protect enterprise value and stakeholder trust in the face of these and other significant risks.

In this context, Deloitte and the USC Marshall School of Business Peter Arkley Institute for Risk Management (USC Marshall Arkley Institute for Risk Management) have conducted their third annual review of risk factor disclosures of Standard & Poor’s (S&P) 500 companies, identifying key trends in the nature and form of these disclosures. This analysis has shown that companies are continuing to report an average of almost 32 risk factors, covering a wide range of risk domains, including strategic transactions, financial, economic, operational, technology, cybersecurity, informational technology, data security, and privacy, legal, regulatory, and compliance, intellectual property, human capital, and market risks. Opportunities remain to better align external risk reporting with internal risk management and reporting processes, improve the readability and categorization of risks, and make disclosures less generic.

We also conducted a deeper review of cybersecurity risk factors this year, given recent Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) rulemaking in this area (Final Cybersecurity Rule).[1] Our analysis showed that many S&P 500 companies have not experienced a material cybersecurity incident,[2] and most made extensive disclosures around the significance of cybersecurity risk to their business, with a focus on the increasing risk created by geopolitical considerations and remote work environments. We also identified challenges in the availability and cost of cyber insurance and the requirement for additional disclosures around cybersecurity governance to comply with the Final Cybersecurity Rule.

Background

Since 2021, Deloitte and the USC Marshall Arkley Institute for Risk Management have conducted a series of analyses on the risk factor disclosures filed by the S&P 500 companies to understand the impact of SEC rules finalized in 2020 to address the increasingly lengthy and generic risk factor disclosures of registrants. For a description of these rules, see Appendix: Summary of SEC’s Final Rule on Regulation S-K, Item 105.

We published our initial results in March 2021, Many companies struggle to adopt spirit of amended SEC risk disclosure rules, reviewing 88 companies that had filed their annual reports by early February 2021. We concluded that risk factor disclosures were becoming lengthier contravening the SEC’s stated intention in the amended requirements. Follow-up reports in November 2021, Limited adoption of amended SEC risk factor disclosure rules: ERM and ESG can chart a path for improved compliance, and December 2022, Climate risk factors soar at largest public companies, reviewing 439 companies, confirmed our initial March 2021 analysis.

In this latest report, we have reviewed the risk factor disclosures in the annual reports of 440 S&P 500 companies to identify trends during this third year of implementation, including an analysis of cybersecurity risk factors. We have also provided recommendations for companies to consider for the next reporting season.

Analysis of Rules Adoption

To assess the adoption of the amended requirements over three years of implementation, we have reviewed the risk factor disclosures of 440 S&P 500 companies that have filed three annual reports between November 9, 2020, the effective date of these requirements, and May 10, 2023. Key findings are as follows:[3]

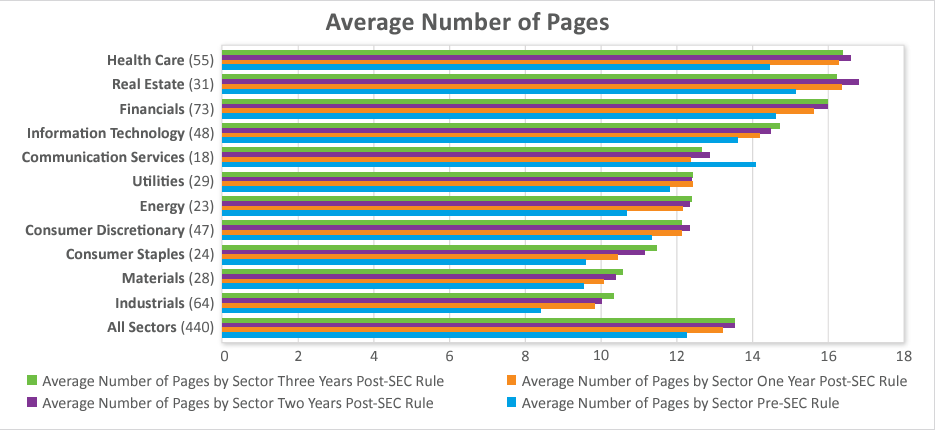

The number of pages has stabilized over the past year, after increasing over the previous two years.

- The average number of pages is about 13.5 per company, the same as the second year after the amendments, but up from about 12 before the amendments and about 13 one year after the amendments. However, 45% of companies increased the number of pages this past year.

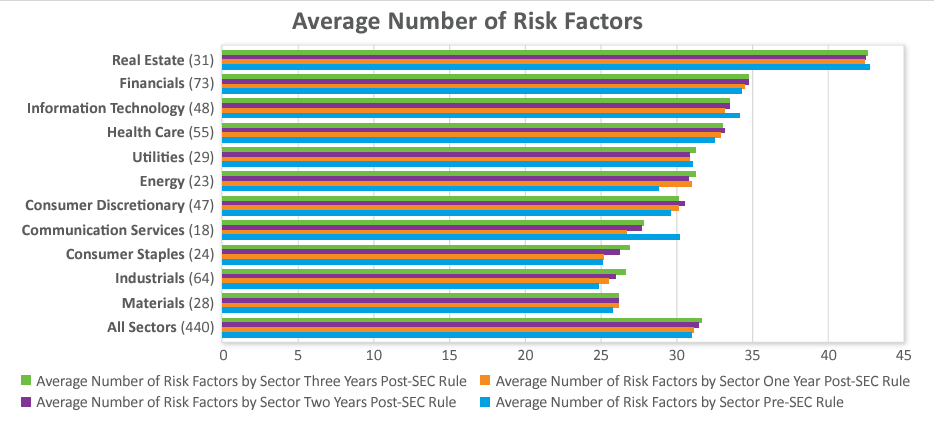

The number of risk factors has also stabilized.

- The average number of risk factors per company was just over 31.5 the third year of implementation compared to just under 31.5 the second year and just over 31 the first year and before the amendments. However, 40% of companies increased the number of risk factors this past year.

Most companies did not need to include a risk factor summary.

- Approximately 22% included a summary in the first year of implementation and 24% in the second year and third year of implementation.

- The average number of pages for the summaries was approximately 1.5 pages all three years of implementation, with a range of .25 to 2.75 pages.

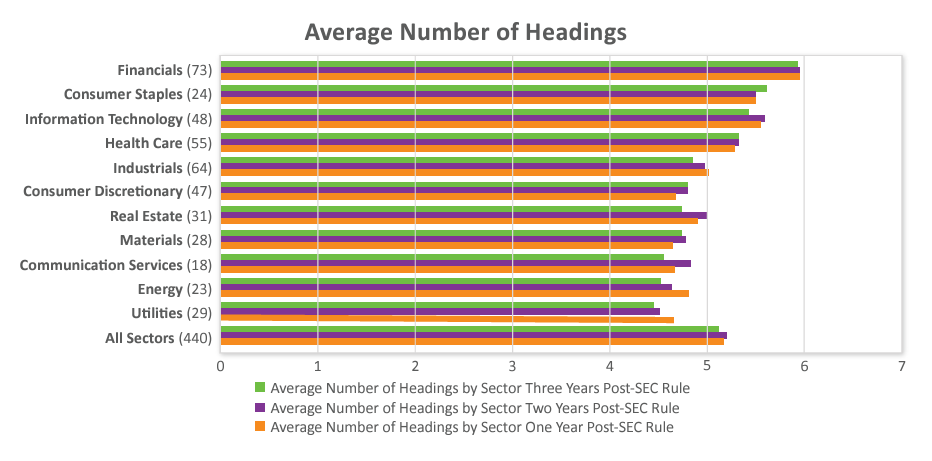

Headings are being used, but they are often very generic.

- Nearly 64% of companies used the same number of headings all three years of implementation.

- The average number of headings per company was five all three years of implementation.

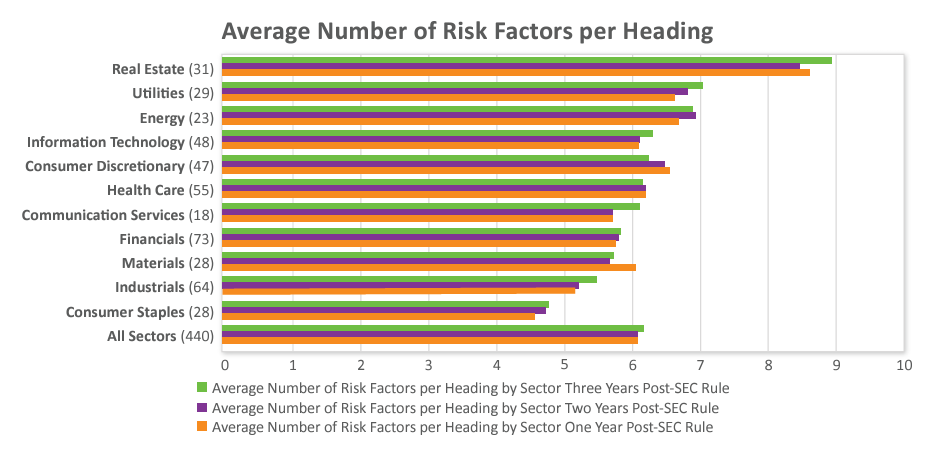

- The average number of risk factors per heading was six all three years of implementation. Over 75 companies included 20 to as many as 44 risk factors under one heading during the third year of implementation.

- The most common heading categories this third year of implementation were variants of legal, regulatory, and compliance; business; operational; financial; cybersecurity, information technology, data security, privacy; common stock; economic and macroeconomic conditions; strategic; industry; strategic transactions; indebtedness; human capital; market; intellectual property; international operations; and tax and accounting.

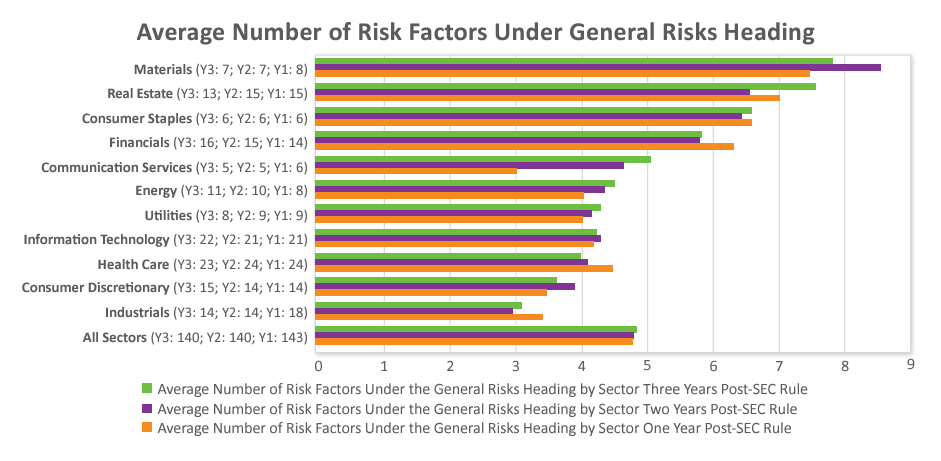

Nearly one-third of companies used a “general risk factors” heading during each of the past three years, contrary to the SEC’s advice.[4]

- Companies used an average of just under five risk factors under the general risk factors heading all three years of implementation and a range of one to 17 during the third year.

- The most common risk factors included under the general risk factors heading during this third year of implementation were recruitment and retention of talent/key personnel; natural and man-made disasters/ catastrophes; stock price volatility; economic conditions; cybersecurity; litigation and/or regulatory investigation; COVID-19; tax law changes; financial reporting internal control weakness; climate change; inability to pay dividends and/or repurchase shares; exchange rate fluctuations; legal and regulatory compliance; and accounting standard changes.

Insights on Cybersecurity Risk Factors

In July 2023, the SEC finalized its much-anticipated Final Cybersecurity Rule, Cybersecurity Risk Management, Strategy, Governance, and Incident Disclosure.[5] This follows upon earlier SEC guidance issued in 2011 by the Division of Corporation Finance, CF Disclosure Guidance: Topic No. 2 – Cybersecurity,[6] and in 2018 by the SEC, Commission Statement and Guidance on Public Company Cybersecurity Disclosures (2018 SEC Cybersecurity Guidance).[7]

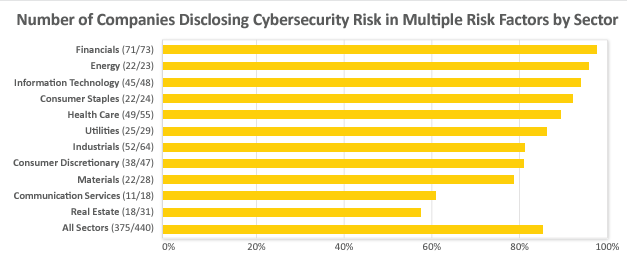

In light of the SEC’s recent rule-making and earlier guidance, using directEDGAR, a tool to search SEC EDGAR filings, we reviewed the cybersecurity risk factor disclosures in the annual reports filed between November 8, 2022 and May 10, 2023 by 440 S&P 500 companies. All 440 companies discussed cybersecurity risk in at least one risk factor, with over 80% discussing this risk in multiple risk factors.

Materiality Analysis

The Final Cybersecurity Rule requires companies to report on Form 8-K a “material” cybersecurity incident within four days of determining the incident is “material.”[8] Given the Final Cybersecurity Rule had not been finalized before the filings of the annual reports we reviewed, we analyzed the risk factor disclosures to identify any cybersecurity incident materiality analysis.

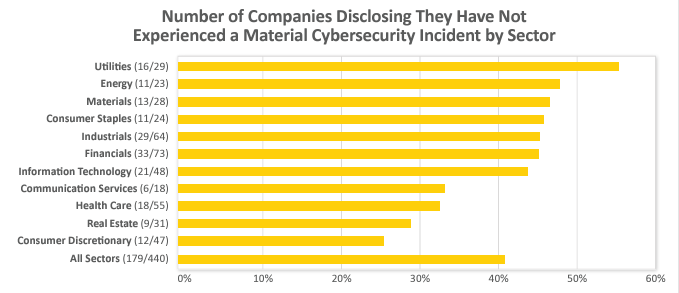

Over 40% of companies, 179 of the 440 companies in our review, disclosed explicitly that they had not experienced a material cybersecurity incident. Over half of those companies stated they had not experienced a material cybersecurity incident “to date,” while most other companies did not include any time period. Eight companies did limit the disclosure to the past year or past three years. Two companies disclosed that they had not experienced a material cybersecurity incident since the date of a previous material cybersecurity incident. Certain sectors were more likely to report that they had not experienced a material cybersecurity incident, with half or nearly half of the companies in the Utilities, Materials, Industrials, Financials, Energy, and Consumer Staples sectors so stating.

Ten additional companies disclosed that they had not experienced a “significant” cybersecurity incident. Over 50% of companies remained silent, not disclosing whether or not they had experienced a material cybersecurity incident.

Approximately 3% of companies disclosed that cybersecurity incidents in the aggregate were not material. Although the SEC’s proposed rule included a cybersecurity incident aggregate materiality analysis, the SEC excluded such an analysis from the Final Cybersecurity Rule.[9]

Cybersecurity Incidents

About 10% of companies, 47 of the 440 companies in our review, discussed they experienced specific cybersecurity incidents, all identifying the date of either the incident, the discovery of the incident, or the announcement of the incident. Only four companies stated explicitly that the incident was “material.” Four noted the incident was “significant.” Thirteen companies stated the incident was not material, another noted the incident was not significant, another, “relatively modest.” The rest of the companies—just over half—discussed neither materiality nor significance.

A few companies discussed cybersecurity incidents impacting a specific industry or a broad group of companies, but not necessarily incidents which they directly experienced. Six companies mentioned the SolarWinds incident, the 2020 supply chain attack where hackers inserted into SolarWinds’ Orion software update malware that infected nearly 18,000 customers. Nine companies, five from the Information Technology sector, mentioned the Log4j vulnerability identified in 2021 in Apache’s widely used, open-source Java logging library. Five companies from the Utilities and Energy sectors disclosed the Colonial Pipeline incident, the 2021 ransomware attack that prompted a six-day shutdown of the pipeline that transports over half the fuel consumed on the East Coast. One company disclosed that the 2022 Okta breach, where hackers accessed data of the user authentication software provider through a subcontractor’s computer, did not have a significant effect.

Factors Heightening Cybersecurity Risk: Geopolitics and Remote Work

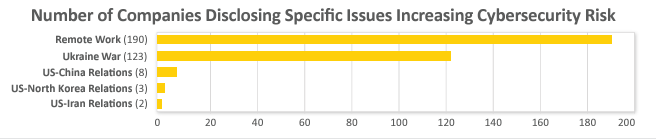

Many companies mentioned that U.S. relations with specific countries have heightened cybersecurity risk: Over 25% of companies noted that the war in Ukraine has amplified cybersecurity risk. Eight companies (five from the Information Technology sector) noted geopolitical tensions with China increased cybersecurity risk. Three companies noted tensions with North Korea heightened cybersecurity risk. Two companies noted tensions with Iran increased cybersecurity risk.

Over 40% of companies noted that remote work has increased cybersecurity risk. Some companies provided reasons for this increase, such as an expanded attack surface with the use of devices, phones, and laptops from a non-office location; the less secure non-office information technology environment; the strain on technology resources and infrastructure given the expanded attack surface; and the explicit targeting of remote workers by cybercriminals. Nine companies disclosed an actual increase in attacks on their remote workers.

Cyber Insurance: Limited Coverage and Costly

The 2018 SEC Cybersecurity Guidance advised companies to consider discussing in their risk factors disclosures “the costs associated with maintaining cybersecurity protections, including, if applicable, insurance coverage relating to cybersecurity incidents or payments to service providers.”[10] Given the hard market around cyber insurance, the continued applicability of the 2018 SEC Cybersecurity Guidance, and the Final Cybersecurity Rule’s focus on disclosures of costs with respect to cybersecurity incidents, we have reviewed the statements on cyber insurance in the risk factor disclosures.

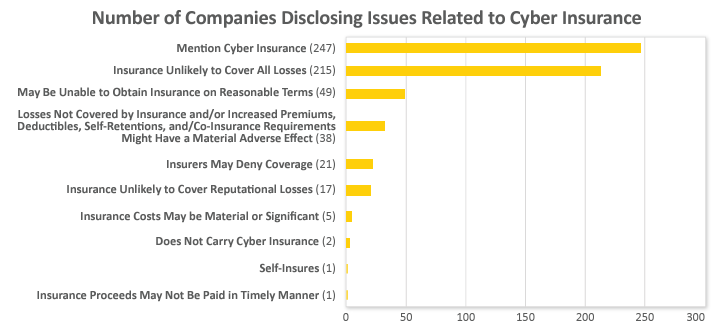

Over half of the 440 S&P 500 companies mentioned cyber insurance in their risk factor disclosures. Nearly half of companies disclosed that their cyber insurance was unlikely to cover all cybersecurity-related losses due to policy scope and/or limits. Nearly 4% of companies stated that their cyber insurance does not or may not cover reputational losses associated with a cybersecurity incident.

Over 8% of companies noted that losses not covered by insurance and/or increased premiums, deductibles, self-retentions, and/or co-insurance requirements might have a material adverse effect

Five companies disclosed that costs related to insurance, including premiums, deductibles, and retentions, could be material or significant.

Over 10% of companies noted they may not be able to obtain cyber insurance on acceptable terms. Nearly 5% of companies mentioned the possibility of their insurers denying coverage of their cyber claims and one company noted that insurance proceeds may not be paid in a “timely manner.”

Two companies explicitly stated that they do not carry cyber insurance, with one of those companies reasoning this lack of insurance was due to costs and restricted coverage. One company noted that it self-insures for cybersecurity risk.

Cybersecurity Risk Management and Governance

Specific disclosure on executive management and board oversight of cybersecurity risk in the cybersecurity risk factors was limited among the 440 companies. The Final Cybersecurity Rule requires disclosure in a new section in the annual report of management positions or committees responsible for assessing and managing cybersecurity risk.[11] Only three companies mentioned in the risk factor disclosures the titles of the executives leading cybersecurity efforts.

The Final Cybersecurity Rule requires companies to identify in annual reports any board committee or subcommittee responsible for cybersecurity risk oversight and how the committee is informed of this risk.[12] In the cybersecurity risk factor disclosures, five companies mentioned that a board of directors oversees or receives updates on cybersecurity risk. Three companies disclosed their audit committees receive regular reporting on cybersecurity risk. One company mentioned its audit committee, nominating and governance committee, and board of directors receive reports on cybersecurity risk. Two companies stated their boards receive annual updates and their audit committees receive more frequent updates. One company mentioned its board and cyber committee receive updates.

No company disclosed board cybersecurity expertise, a proposed requirement that the SEC excluded from the Final Cybersecurity Rule.[13]

Considerations

Integrate risk factor disclosure processes, including cybersecurity risk disclosures, with enterprise risk management (ERM) reporting processes. The SEC requires in the Final Cybersecurity Rule for companies to discuss if the processes for identifying, assessing, and managing cybersecurity risk are integrated with their overall risk management processes. As we have recommended in each of our past reports, companies should consider integrating their risk factor disclosure process into their ERM reporting processes and dynamic risk programs. Companies may then be better positioned to meet the SEC’s goals set forth in the amended risk factor disclosure requirements of “disclosure that is more in line with the way the registrant’s management and its board of directors monitor and assess the business.”[14] In addition, given that a centralized ERM function typically maintains an internal risk register of material risks, this could also contribute to meeting the materiality standard set forth in the amended risk factor disclosure requirements. From a business perspective, better alignment between ERM and risk factor disclosures can increase focus on the most significant risks facing the organization and increase confidence in how risk is viewed and managed to achieve strategic goals.

Align cybersecurity disclosures in securities filings. The Final Cybersecurity Rule requires companies to disclose a cybersecurity incident on Form 8-K within four days of determining that the incident is material. It also requires companies to report items relating to cybersecurity risk management and governance in a new section in the annual report.[15] Our analysis of risk factor disclosures has shown that some companies are disclosing in their cybersecurity risk factors items required under the Final Cybersecurity Rule. During this upcoming reporting season and going forward, companies should consider reviewing and aligning their cybersecurity risk factors with the Final Cybersecurity Rule disclosures.

Shorten sentence length. We have now reviewed four reporting seasons of risk factor disclosures. The SEC’s amended risk factor disclosure requirements have overall not prompted our largest public companies to make their disclosures more readable, a key purpose of these requirements.[16] We believe the greatest salve to readability would be for companies to decrease the number of words in each sentence in line with Plain English standards for sentence length (no more than 20 words per sentence).[17] Companies could start this exercise by shortening their subcaptions.

Use risk taxonomies from ERM program for headings. Companies continue to use generic headings, such as “business” risks, “industry” risks, and “operations” risks. To bring more specificity to headings and enhance readability, companies could rely on their internal taxonomies used to catalogue risks for their ERM and risk reporting to management and boards of directors. This could lead to the more integrated external and internal reporting the SEC sought in the revised risk factor disclosure rules. Avoid generic risks. The SEC suggested in its amended requirements that companies avoid using a “General Risk Factors” heading. However, one-third of companies have used this heading in the past three reporting seasons.[18] If companies are disclosing these “general” risks to their management and boards, companies could use the more descriptive headings they use in their risk taxonomies for management and board reporting.

Conclusion

During this third year of implementation of the SEC’s amended requirements, risk factor disclosures of 440 S&P 500 companies, after generally becoming lengthier the previous two years, are stabilizing. Some of the length in the two previous reporting seasons was due to the introduction of new standalone risk factors related to COVID and climate. In addition, we believe the SEC’s focus on companies’ integrating cybersecurity risk management processes in the Final Cybersecurity Rule and climate risk management processes in the proposed climate disclosure rule[19] with their overall risk management processes provides companies the opportunity to enhance and more fully integrate their risk factor disclosure processes with their ERM reporting processes.

Appendix: Summary of SEC’s Final Rule on Regulation S-K, Item 105

| Topic | Rule Text | What It Means |

| Disclosure of “Material” Risks | Where appropriate, provide under the caption “Risk Factors” a discussion of the material factors that make an investment in the registrant or offering speculative or risky. (§229.105(a)) | To focus risk factor disclosures, companies should disclose only “material” risks, those “to which reasonable investors would attach importance in making investment or voting decisions.”[20] The previous rule required the disclosure of an organization’s “most significant” risks. |

| Use of Headings | This discussion must be organized logically with relevant headings and each risk factor should be set forth under a subcaption that adequately describes the risk. The presentation of risks that could apply generically to any registrant or any offering is discouraged, but to the extent generic risk factors are presented, disclose them at the end of the risk factor section under the caption “General Risk Factors.” (§229.105(a)) | To improve the organization and readability of risk factors, companies should place risk factors into related groupings under headings, with generic risk factors grouped together under a “General Risk Factors” heading. |

| Risk Factor Summaries for Longer Disclosures | Concisely explain how each risk affects the registrant or the securities being offered. If the discussion is longer than 15 pages, include in the forepart of the prospectus or annual report, as applicable, a series of concise, bulleted or numbered statements that is no more than two pages summarizing the principal factors that make an investment in the registrant or offering speculative or risky. (§229.105(b)) | To “enhance the readability and usefulness” of risk factor disclosures, companies with risk factor disclosures that are more than 15 pages must include a summary of their risk factors of no more than two pages.[21] |

Endnotes

1SEC, Final Rule: Cybersecurity Risk Management, Strategy, Governance, and Incident Disclosure, Release No. 33-11216 (July 26, 2023) [88 FR 51896 (August 4, 2023)] [hereinafter Final Cybersecurity Rule].(go back)

2The Final Cybersecurity Rule states that “information is material if ‘there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable shareholder would consider it important’ in making an investment decision, or if it would have ‘significantly altered the ‘total mix’ of information made available.’” Id. at 51900 (footnotes omitted).(go back)

3In this report, we have used the sectors set forth in the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS). We have disclosed average data rather than median data given the limited difference between the average data and median data for the 440 S&P 500 companies reviewed.(go back)

4Securities and Exchange Commission, Final Rule: Modernization of Regulation S-K Items 101, 103, and 105, Release No. 33-10825 (Aug. 26, 2020) [85 FR 63726, 63761, §229.105(a) (Oct. 8, 2020)] (“The presentation of risks that could apply generically to any registrant or any offering is discouraged, but to the extent generic risk factors are presented, disclose them at the end of the risk factor section under the caption ‘General Risk Factors.’’’) [hereinafter Final Rule].(go back)

5Final Cybersecurity Rule.(go back)

6SEC, CF Disclosure Guidance: Topic No. 2 – Cybersecurity (October 13, 2011).(go back)

7SEC, Commission Statement and Guidance on Public Company Cybersecurity Disclosures (February 21, 2018) [83 FR 8166 (February 26, 2018)] [hereinafter 2018 SEC Cybersecurity Guidance].(go back)

8Final Cybersecurity Rule at 51944-45, Appendix C—Form 8-K, Item 1.05.(go back)

9Final Cybersecurity Rule at 51910.(go back)

102018 SEC Cybersecurity Guidance at 8169.(go back)

11Final Cybersecurity Rule at 51942, §229.106(c)(2).(go back)

12Id. at 51942, §229.106(c)(1).(go back)

13Id. at 51898.(go back)

14Final Rule at 63748.(go back)

15Final Cybersecurity Rule at 51942-45, §229.106 and Appendix C—Form 8-K, Item 1.05.(go back)

16Final Rule at 63726 (“Specifically, the amendments are intended to improve the readability of disclosure documents, as well as discourage repetition and the disclosure of information that is not material.”).(go back)

17Martin Cutts, Oxford Guide to Plain English, 5th ed. 22 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, Feb. 27, 2020).(go back)

18Companies may be disclosing these generic risk factors with the aim of these disclosures being afforded the “meaningful cautionary statement” safe harbor under the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act. See Final Rule at 63745 for the SEC’s description of a comment letter on the proposal describing the use of the risk factor disclosure to satisfy the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act safe harbor. See also SEC, Concept Release: Business and Financial Disclosure Required by Regulation S-K, Release No. 33-10064 [81 FR 23916, 23955 (Apr. 22, 2016)].(go back)

19SEC, Proposed Rule: The Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors, Release No. 33-11042 [87 FR 21334 (April 11, 2022)].(go back)

20Final Rule at 63744.(go back)

21Id. at 63743.(go back)

Print

Print