Lauren H. Cohen is the L. E. Simmons Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, Umit Gurun is the Stan Liebowitz Professor of Accounting at the University of Texas at Dallas, and N. Bugra Ozel is an Associate Professor of Accounting at the University of Texas at Dallas. This post is based on their recent paper.

The common perception of managerial positions is that they come with more responsibility and oversight authority. For instance, managers frequently oversee budgets and work schedules, Additionally, they can influence recruiting, promotion, and firing decisions. Managers often receive higher salaries, additional types of compensation (such as bonuses), and perquisites than non-managerial staff in keeping with their increased responsibility. “Managers” are recognized as a distinct and distinctive class by the Federal Government, as well. In fact, to determine who is eligible for overtime compensation, the federal government has gone so far as to establish a law that distinguishes between managers and normal employees.

The Fair Labor Standards Act §7(g) (hereafter FLSA) exempts employers from making overtime payments to employees who are “managers” and are paid a salary above a threshold. Using this provision, we investigate whether firms appear to strategically assign titles to exploit regulatory thresholds to avoid paying for overtime work. For instance, we investigate the extent to which companies hire employees with potentially deceptive managerial job titles with otherwise equivalent work parameters as other non-managers to avoid having to pay overtime for extra hours worked. Below, we provide a few examples of such deceptive managerial titles:

|

Employee |

Manager |

|

Receptionist |

Front Desk Manager |

|

Front Desk Clerk |

Director of First Impressions |

|

Reservation Clerk |

Lead Reservationist |

|

Host/Hostess |

Guest Experience Leader |

|

Carpet Cleaner |

Carpet Shampoo Manager |

|

Asset Protection Specialist |

Asset Protection Coordinator |

|

Barber |

Grooming Manager |

|

Food Cart Attendant |

Food Cart Manager |

As an illustration of the idea we study, consider the Family Dollar Store, which was alleged to have given a disproportionate share of employees managerial titles such as “Store Managers.” While these employees occasionally performed managerial duties, they essentially spent 60 to 90 hours a week performing manual labor tasks such as “stocking shelves, running the cash registers, unloading trucks, and cleaning the parking lots, floors and bathrooms,” according to a class-action suit filed in 2008. The plaintiffs also claimed that “store managers spent only five to 10 hours of their time managing anything.” In this case, the court ruled that Family Dollar fabricated job titles that did not accurately describe the employees’ daily routines. It awarded $35 million in unpaid overtime pay to 1,424 employees.

Family Dollar Store’s case is not an outlier. Wage theft-related violations are second only to workplace safety violations in terms of corporate violations. According to Department of Labor enforcement data, between 2010 and 2021, approximately 73% of wage theft violations that resulted in fines or back-wages included overtime-related charges, and back-wages owed for overtime accounted for more than 80% of total back-wages and fines. Perhaps more strikingly, overtime violations are nearly twice as common as environmental and employment discrimination violations combined.

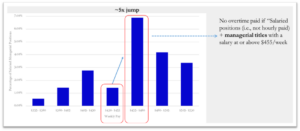

Our central finding is that there is a systematic, robust, and sharp increase in firms’ use of managerial titles around the federal regulatory threshold that allows them to avoid paying for overtime as seen in the below figure. In particular, we see a sharp increase in the usage of managerial titles for salaried employees just above the salary threshold set in the Federal Labor Standards Act ($455/week) – allowing the firms to avoid paying overtime compensation to these workers. In addition, many of these “managerial” titles seem questionable (such as Director of First Impressions and Assistant Bingo Manager).

In contrast, we do not observe any similar spikes in managerial titles around any other thresholds besides that set forth by the FLSA. Additionally, we do not observe such jumps in managerial titles around the FLSA threshold in five states that augmented laws to the FLSA and do not use the FLSA’s overtime exemption threshold. Finally, for firms to avoid paying overtime to a managerial employee, the employee’s pay must be above the regulatory threshold, and the position must be salaried. We thus also explore the prevalence of managerial titles for hourly employees of the same firms and same places that do spike their demand for salaried “managers” at the given FLSA threshold. Holding the compensation threshold fixed at $455, we find no such jumps in the use of managerial titles for hourly employees (whose overtime cannot be avoided through the conferring of the manager title) by these same firms.

We also document that having salaried positions with managerial titles that pay just above the overtime threshold is strongly associated with future Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division enforcement actions, suggesting labor market authorities can utilize our measure as a timely and affordable indicator of overtime avoidance.

We then delve deeper to investigate the factors that affect firms’ tendency to offer positions that marginally avoid overtime payments. We find that firms are more likely to use managerial titles strategically when they have more bargaining power and laws governing employee protection are weaker. In particular, where state laws are less protective of worker rights, the strategic use of managerial titles is more than 50% higher. Furthermore, we find that in retail, food/drink services, janitorial/housekeeping services, and hotel industries, all of which are considered as low-wage/high-violation industries by the Department of Labor, firms are more intensive users of strategic managerial titles for overtime avoidance.

One might still ask if some unobservable firm- or industry-level characteristic could be driving the relationships we see regarding the seemingly strategic use of managerial titles. For this to be the case, the characteristic would have to occur: i.) solely at the $455/week threshold, but not at other nearby thresholds; ii.) occur only for salaried (but not hourly) employees in states that follow FLSA (but not in non-FLSA states) even at this exact threshold; iii.) be stronger (more prevalent) in instances where employees have less bargaining power, where firms have more bargaining power, and even within the same locations, and be more present for firms facing financial constraints. The confluence of precisely these dynamics and relations in these particular patterns seem otherwise somewhat unlikely.

To investigate the abovementioned channel in even more depth, we focus on a subset of our sample firms that operate establishments in multiple states concurrently. For these firms, we run a finer test, including firm fixed effects, to see whether within the same firm, we see evidence of more overtime avoidance through the strategic use of titles in the places where the firm’s bargaining power is greater. The clear advantage of this test is that because it exploits variation within the same firm, it controls for any differences across firms that one might worry could be driving any of the relations. This is particularly true for the more homogeneous unit economic firms we observe (e.g., Panera in Plano, TX vs. Cambridge, MA). We find strong evidence that the same firms appear to engage significantly more in the strategic use of titles for overtime pay avoidance in states where they have relatively greater bargaining power. Moreover, firms in the sub-sample of high FLSA violation industries (many of which happen to also be in more homogenous production structures such as retail and food service) exhibit even larger effects. Lastly, we find that our results persist strongly and significantly through the present-day, in fact being even larger in point estimate in the recent period.

In follow-on tests, we examine the relation between firms’ incentives and overtime avoidance. Using local credit supply shocks from oil shale well discoveries, we find evidence that firms’ financial constraints play a role in their usage of overtime avoidance practices. We also find that overtime avoidance is higher when firms face less competition in the labor market for the positions they are hiring, consistent with firms using the overtime rule exemption rules more intensively when they have more bargaining power vis-à-vis labor supply. Additionally, when the labor pool is better educated, firms tend to offer fewer overtime-avoiding positions, potentially due to increased labor mobility and the legal consciousness of employees.

The complete paper is available for download here.

Print

Print