Maria Moats is a Leader and Stephen Parker is a Partner at the Governance Insights Center, PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. Kristin Rivera is a Partner and the Global Forensics Leader at PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. This post is based on their PwC memorandum.

What is the audit committee’s role?

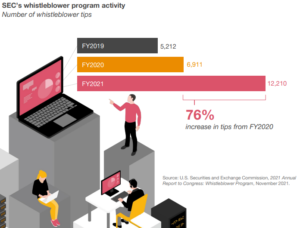

Companies are getting more whistleblower tips and complaints. Shareholders, employees, and regulators expect companies to follow up, and resolve any issues. For many companies it is not a matter of if a significant complaint will occur—but when. And given the size of some whistleblower settlements, the incentive to speak up is growing.

Complaints often involve a possible economic loss to the company and have accounting, internal control, and disclosure ramifications. As a result, the audit committee is usually called upon to oversee or direct an internal investigation.

What type of claims trigger an investigation?

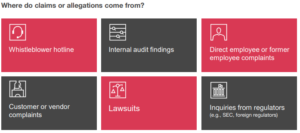

Investigations can be triggered by a variety of complaints. They range from allegations of financial reporting fraud, bribery, and conflicts of interest to harassment and cyber breaches. Some of these activities could violate company policy, while others could also violate laws, such as the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

To investigate or not?

Companies receive all kinds of complaints from internal hotlines and other sources. Whistleblowers can file complaints directly with the SEC as well. Some complaints stem from harmless squabbles between employees. Others might involve illegal acts that could have a material economic and reputational impact on the company. Some may have already hit the media, possibly creating a crisis situation. All complaints require some level of follow up by management. But deciding which require a more extensive investigation is a judgment call. This decision to investigate is a key component of management’s compliance function which typically requires the oversight of the audit committee. And given the likelihood that regulators, including the SEC or Department of Justice (DOJ), may assess the effectiveness of the company’s investigation, all parties should be aligned on the scope and results.

Audit committee members should ask: how do we know if management’s follow up is sufficient, and what level of detail should we receive from management? The answer often depends on the volume of complaints and the company’s risk assessment. For example, even a perceived low risk complaint may be of interest to the audit committee if it relates to a highly-sensitive geography, business unit, or leader, or if it is an indicator of a trend or theme or fraud. Depending on company size and the volume of complaints, one practice for committees to consider is to have management provide the audit committee chair with certain details of complaints at least quarterly, such as the nature of the complaint, preliminary risk assessment, and the business unit(s) and geographic location(s) possibly impacted. This allows the chair to evaluate the appropriateness of management’s response and identify any trends. If the complaint volume is high due to the size of the company, it may be more practical for management to provide a quarterly summary of complaints, with a periodic deeper dive into the details. The chair then brings to the full committee what he or she believes it needs to weigh in on.

It is important to have an established written escalation protocol for significant complaints—this could be a job for the audit committee chair. Escalation policies should be as specific as possible to make sure that all parties understand the plan. For example, matters that could impact the company’s financial reporting, the integrity of management, the external audit, or could have potential media impact should be brought to the attention of the audit committee chair right away.

This allows the chair to weigh in on urgent decisions of whether and how to investigate. The protocol should be reviewed annually to ensure it is still applicable and makes sense for the company.

Ask the following five questions to determine the extent to which an allegation may warrant oversight by the audit committee:

- Does the allegation point to a possible misstatement of current or historical financial statements?

- Could the allegation result in fines, penalties, or other financial contingencies or require a change to financial disclosures?

- Could the alleged issue give rise to a material weakness or significant deficiency in internal controls?

- Does the allegation involve key personnel (senior leaders, representation signers, etc.)?

- Does the allegation suggest that action may be needed to prevent public harm from occurring or continuing to occur?

The Commission made more whistleblower awards in FY2021 [$564 million] than in all prior years combined.

–Emily Pasquinelli

Acting Chief, Office of the Whistleblower, November 2021

Other factors to consider when assessing the appropriate level of board oversight may include the pervasiveness of the allegation, potential impact on brand, management’s ability to respond objectively, and whether the allegation could affect controls on which the audit team is relying and/or considering for purposes of their opinion.

When a company doesn’t effectively investigate an allegation, it can lead to other issues such as negative press, damage to the company’s brand, increased litigation risk, or more attention from regulators, such as the SEC and DOJ. Proxy advisory firms have also recommended against voting for directors who failed to undertake credible investigations, adding to the pressure.

You have decided to investigate…now what?

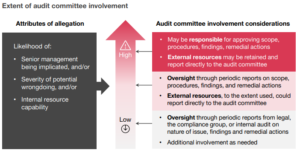

The more significant the allegation, the more involved the audit committee should be in overseeing or leading the investigation and determining the appropriate resources.

Any investigation needs to be conducted by an objective party. The underlying facts of the allegation will impact who that would be. For example, if the claim casts suspicions on upper management, the investigation should be led by the audit committee or a special committee of the board.

Getting it right matters. A well-planned and well-executed investigation enables an effective and efficient response to potential regulatory or other inquiries.

Do we need independent board oversight?

In some cases, independent director oversight is called for. This includes allegations that could pose significant economic loss or reputational harm to the company, or when its executive management could be involved. In the latter case, the investigation is usually overseen or possibly directed by the audit committee. It’s a natural fit given the requirement that this committee’s members be independent, as well as their financial reporting oversight and fraud deterrence responsibilities, such as oversight of the whistleblower hotline. While uncommon, if one or more members of the audit committee are conflicted, some boards form a special committee of independent directors. In rare cases, an independent director with specialized skills (e.g., cyber experience in a cyber fraud allegation) could be asked to join a special committee.

Installing a board committee as the leader of an investigation can be a difficult decision. This is especially true when the allegations involve executive management. This can be a sensitive decision that can strain the board’s relationship with management. By design, management will no longer have full visibility to the scope and execution of the investigation or be able to manage the costs being incurred by outside resources, such as external counsel.

This is an important time to ensure you have the right chair for the independent committee. Experience, healthy skepticism, integrity, strong communication skills, and bandwidth are critical. Investigations can involve challenging decisions and important communications to stakeholders under severe time pressure.

How do we select the investigation team?

What should you look for in an investigation team? Objectivity, subject matter expertise, and bandwidth. The severity of the allegations and the underlying facts also dictate if external resources will be necessary.

Depending on the sophistication of the company and the capabilities of their internal resources, including the ability to conduct the investigation under attorney-client privilege, the investigation of less significant allegations can sometimes be handled by in-house legal, compliance, and internal audit teams. With their institutional knowledge, these internal teams can save time and money. If the matter involves someone from management or requires a particular expertise, tools not available in house, or foreign language skills that exceed the internal team’s capabilities, the audit committee may consider bringing in outside resources.

For more significant allegations, the committee will want to call on external resources. They will bring the objectivity and experience that regulators and external auditors expect. The critical decision is to engage the right external legal counsel to lead the investigation team. They, in turn, may engage others to assist them, such as forensic accountants.

When it comes to external legal counsel, the company’s regular law firm may not be the right choice. They already have a relationship with management, which could impair their ability to be objective. But objectivity is not the only factor. The outside counsel should also have experience in conducting similar investigations to minimize inefficiencies or worse, the need for a redo.

Being part of an internal investigation was the most challenging experience of my board service.

–Board member

Preparing for the worst: be ready before an investigation arises

Companies and their boards should expect pressure to complete significant investigations quickly. Here’s how to make the investigation more efficient, avoid missteps, and execute a thoughtful investigative process.

Line up the right outside advisors

Consider identifying and retaining objective external legal counsel in advance of a significant issue arising. Also, consider on call agreements with forensic accountants or providers who will assist with the process of discovering documents significant to any litigation.

Ensure communication protocols are in place

When significant trouble confronts a company, management will be keenly focused on communicating with key stakeholders—shareholders, employees, external auditors, vendors, lenders, and regulators. Companies should establish internal communication protocols and have a plan for ensuring that the audit committee, general counsel, disclosure counsel, and the investigation team collaborate to provide factual and timely communications.

Perform table-top exercises

Simulation crisis exercises are one tool companies use to prepare to respond to an allegation of wrongdoing. They can also help senior executives and directors understand their roles and responsibilities.

Establishing scope and procedures— how much is enough?

After establishing the right oversight committee and investigation team, the next task is to define the scope of the investigation. For example, should you limit the scope of the investigation to the one business unit cited in the allegation, or do you immediately expand the scope after considering the risk that the issue is more pervasive—maybe even company wide? Getting the scope right upfront will help avoid delays and costs down the road. Ensuring the scope meets the needs of the external auditors may also help avoid unnecessary issues or questions later.

For significant investigations, the committee may feel considerable pressure from stakeholders to complete the process on a very short timeline. But determining the scope of the investigation and the nature of investigation procedures is key and needs to be a priority. While it is the company’s duty to meet financial reporting deadlines if possible, conducting an appropriate investigation should not be compromised by deadlines.

Common causes of delays in investigations: areas to be managed

- Initial scope too narrow or too broad

- Insufficient company resources to obtain documents and accounting records

- Failure to retain experienced external investigations counsel

- Need for complex forensic accounting effort

- Late decision by investigation team to communicate findings in a written report rather than orally requiring management and external auditors to create documentation

Committee members should push back on the scope and/or procedures recommended by external legal counsel if they believe they are inadequate—or too broad. Be mindful that investigations can take unexpected turns along the way as additional findings come to light and the scope should be adjusted accordingly. There have been numerous situations when a company announced the results of an investigation only to realize that the issue was more pervasive than originally thought. This could compound the reputational impact on a company.

How does the committee stay informed?

Throughout the investigation, regular updates to the audit committee by the investigation team are essential. The committee should continue to weigh in—and push back, if needed—on the planned scope and procedures of the investigation, as well as whether it should be expanded or reduced based on findings to date. And be prepared. The number of committee meetings and updates with the investigation team and full board could be extensive.

An investigation can also take a significant amount of management’s time. Management can easily lose the balance between the investigation and keeping the business on track. The audit committee and members of the investigation team should check in with management periodically to evaluate the need to add additional resources or make other corrections depending on the level of disruption.

It is important for the audit committee and investigation team not to discuss details of the investigation’s scope, procedures, or findings with any potential witnesses, including members of management. However, members of management will need periodic status updates on certain aspects, such as estimated investigation timing, employee resource expectations, and any impact on financial reporting, so that they can plan and perform their job duties effectively. This also applies to the external auditors.

Does the company need to self-report to regulators, disclose the allegations, or delay its SEC filings?

Regulators, such as the SEC and DOJ, expect and encourage the company to self-report when there are significant allegations. The regulators may want the company to communicate its investigation plan and provide periodic status updates. But the decision to self-report to regulators is complex. The SEC Enforcement Division’s Cooperation Program provides benefits to companies that cooperate, ranging from reduced charges and sanctions in enforcement actions to no enforcement actions at all. A related question is whether the existence of the investigation needs to be disclosed in an SEC filing, and if so, when. The advice of legal counsel is critical for both of these questions.

If the allegations could be material to the company’s financial reporting (qualitatively or quantitatively), the company may need to delay its SEC filings until the investigation can be completed. Delays can trigger declines in stock price, violations of loan covenants, and restricted access to the capital markets. These unwelcome consequences underscore the importance of timely communication. At the same time, disclosing deficient or erroneous information that needs to be updated or corrected can undermine credibility and lead to consequences with regulators.

How do we involve the external auditors?

Directors may be wary of involving the external auditors before they have evidence of wrongdoing, but it is critical to be aligned from the beginning. It is important to understand that auditors have professional responsibilities under the auditing standards, international professional ethics standards, and Section 10A of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. The audit team may need to perform substantial work and involve forensic specialists if the allegations relate to fraudulent financial reporting or the integrity of senior management (even if not related to financial reporting), or if the claim could result in material penalties or fines.

Involving external auditors at the outset of the investigation and being transparent about the allegations and the company’s planned response is a leading practice. Seeking their input early also helps avoid unnecessary costs and delays if they believe the initial scope and procedures are too narrow or inadequate and revisions are required.

The investigation procedures are completed—what should we document and communicate?

Once the investigation procedures are complete or nearly complete, the next step is documenting and communicating the findings. Some investigation teams or committees prepare detailed written reports. Others document their work in bullet point format in a slide deck. Still others communicate their findings to stakeholders orally rather than in a written report.

There is no one right answer. But it is critical that the parties decide on the form of documentation as early in the process as possible. This could cause delays in completing the investigation and possibly delays in meeting quarterly or annual SEC filing deadlines. The importance of consulting with legal counsel cannot be stressed enough. However documented, the investigation findings will be scrutinized and ultimately used by stakeholders, including management, external auditors, and likely regulators.

In weighing the pros and cons of different reporting formats, consider the following:

- Findings and any remediation plan should be thoughtfully crafted, as they may form the basis of future public disclosures, if any.

- The board and audit committee will need to demonstrate that they fulfilled their fiduciary duties.

- Management will need documentation of the investigation’s procedures and findings to substantiate their assessment of the impact on financial reporting and internal controls.

- Regulators, external auditors, or others will likely request access to a written report. If a single privileged report is used and the external auditor requires access, the attorney client privilege may be waived. If written privileged communications are thought to be necessary, discuss the options available to provide the appropriate information to the external auditor or others.

The dust has settled—what is the remediation plan?

After the investigation is complete, the important task of devising a remediation plan falls to the investigation team and the audit committee. Depending on the circumstances, the remediation effort can be extensive and lengthy. Management will need to devote appropriate resources and establish a process to keep the audit committee updated on progress.

Important questions to consider when recommending remedial action for management include:

- Who was aware of or participated in the wrongdoing?

- What actions were taken or should have been taken?

- What policies, procedures, or internal control modifications are needed to prevent a recurrence?

Remediation plans should also address any situations in which management or the external auditors will be unable to rely on the representations of those individuals involved. Objectivity continues to be vital. Outside advisors can play a key role helping the committee make well-informed decisions, especially when decisions involve members of senior management.

The company’s system of internal control over financial reporting must also be assessed for the existence of any significant deficiencies and whether they rose to the level of a material weakness.

Overseeing or leading an investigation is a critical responsibility of the audit committee. Having the right investigation team and approach is important. Being prepared and devising and executing a high-quality investigation will provide value under challenging circumstances.

Print

Print