Maria Castañón Moats is a Leader; Stephen Parker is a Partner; and Tracey-Lee Brown is a Director at the Governance Insights Center, PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. This post is based on their PwC memorandum.

Today’s boards are increasingly being asked to up their game—by regulators, investors, and proxy advisors. Audit committee workloads are growing and often include overseeing complex areas such as cybersecurity and elements of ESG. The entire board relies on the hard work of the audit committee to meet its overall objectives. But many audit committees are asking whether they have the right approach to meet these demands.

Audit committees need to find ways to meet the heavy burden of regulatory mandates, keep up with increasing stakeholder expectations, and find time for unforeseen issues. Here are some ideas for the audit committee chair to build the right audit committee and keep members performing at a high level.

Effective oversight by strong, active, knowledgeable, and independent audit committees significantly furthers the collective goal of providing high-quality, reliable financial information to investors.

–Paul Munter

Acting Chief Accountant, SEC, October 2021

The audit committee chair: cornerstone of the committee

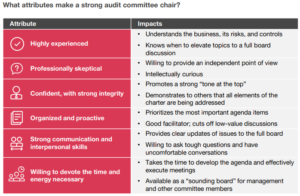

A high-performing audit committee starts with a good chair. Good leadership and effectiveness go hand in hand. Effective chairs can bring out the best in other committee members, management and external auditors.

Audit committee chairs need to have experience, integrity, and strong communication skills. To be truly effective, he or she has to take the time to really work on the committee agenda and make sure meetings run well. The chair must be able to effectively coordinate with other board committees. For instance, the audit committee needs to coordinate with the compensation committee to provide input on whether adjustments to GAAP profit measures used to determine CEO incentive compensation are appropriate and accurately calculated. A strong chair also makes him or herself available to senior management, internal audit, and the independent auditors in between scheduled committee meetings for important matters.

What should the audit committee’s composition look like?

A key responsibility of the audit committee chair is to think about the committee’s overall composition. This means having the right people with the right skill sets to fulfill committee responsibilities.

NYSE and NASDAQ requirements for audit committee composition*

*Companies need to work with company counsel to ensure compliance. |

An effective audit committee goes beyond just meeting the stock exchange requirements listed above. While nearly all directors tell us that financial expertise is a very important attribute on their board, more than half also say the same about risk management expertise. These skills are especially important for audit committee members, as boards typically delegate much of risk oversight responsibilities to the audit committee. Also, since audit committees are often charged with oversight of cybersecurity risk, digital and cyber skills are important as well.

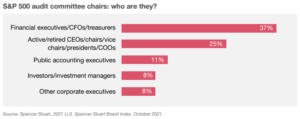

Diversity can bring real benefits to a board—and to an audit committee. For example, about threequarters (76%) of directors believe that board diversity improves their board’s approach to strategy and risk oversight. Diversity comes from having a variety of viewpoints. When it comes to business experience, having a mix of both active and retired financial executives, CEOs, risk professionals, and public accounting executives can provide a range of views and perspectives.

When an audit committee has only one member who is a “financial expert,” that person often serves as chair. When this is the case, the chair needs to take care to use that expertise as a resource, but also to ensure that he or she doesn’t dominate discussions. Audit committee members with other types of skills and expertise can provide valuable perspectives that enhance the dialogue and improve the committee’s oversight.

When assessing what’s needed on the audit committee, it’s important not to overlook “soft” skills. Skills like negotiation, teamwork, problem solving, and communication can complement the critical “hard” financial and technical skills that audit committees need.

A good audit committee will also have members who maintain the respect and trust of their peers and management and understand their role in deterring fraud. If there are allegations of wrongdoing by company personnel, audit committees may be tasked with performing an investigation and forming conclusions on behalf of the board. Committee members should have the integrity and objectivity necessary to deal with any bad actors. Refer to Appendix B for specific tips to consider related to the board’s role in deterring fraud.

Confronting a crisisWhile crisis response planning is management’s responsibility, the board should have oversight of the plan content and the results of testing. And the board should understand how crises are escalated to the board. Typically, a response plan will lay out various types of crises and the protocol for managing each. The role the audit committee plays in the company’s crisis management program is becoming increasingly important. Why? If a whistleblower claim comes into the company, the audit committee chair will typically be notified, depending on nature and severity. Also, a number of audit committees are overseeing cybersecurity risk, which should be one of the types of crises in the plan. For more information, read: |

Too big, too small, or just right?

Most audit committees are made up of three to six members, with four being the most common. We believe that four members is typically the right size for audit committees. Keeping the audit committee on the smaller side promotes efficient discussions and makes it easier to schedule meetings. And in the event of unforeseen member turnover, having four members instead of the minimum of three may provide continuity. For the same reason, audit committees should ideally have at least two audit committee financial experts. Most companies seem to agree, since 84% of companies in the S&P 500 and 75% of companies in the S&P 1500 have audit committees with more than one financial expert.

Financial experts: what to disclose?SEC rules require companies to disclose in their proxy statement whether the audit committee has at least one financial expert. If so, the person’s name and independence must be provided. Some companies choose not to disclose other audit committee members who are also financial experts—because it isn’t required. But we encourage companies to disclose the names of all members who meet the definition of a financial expert. This enhances transparency for investors. |

Some institutional investors and proxy advisory firms have expressed concerns about the “overboarding” of directors. And there are specific rules that apply to some audit committee members. Directors of companies listed on the NYSE are required to get approval from each board if they serve on more than three public company audit committees. Given the time commitment involved with most audit committees, the audit committee chair should regularly assess possible “over-boarding” of audit committee service by its members

Refreshment through rotation

Director tenure is a topic of debate for boards and investors alike. Longer-tenured members have deep experience, understand the business and know how the company works. But long tenure can sometimes breed complacency and a perceived lack of independence from management. To promote refreshment on the audit committee, many boards rotate membership. We believe a board rotation policy can provide effective refreshment. A term of five to seven years, with some flexibility for special situations, is a reasonable term to balance institutional knowledge with fresh ideas from new members.

| 42% of S&P 500 boards limit the number of other audit committees on which a director can serve. Of those, nearly all allow members to serve on up to two other audit committees

Source: Spencer Stuart, 2021 U.S. Spencer Stuart Board Index, October 2021. |

Getting (and staying) up to speed

It’s one thing to have a good audit committee in place. But the audit committee chair needs to take a lead role in helping get new members up to speed. A structured process is critical to successful onboarding. It should start with a comprehensive meeting with the audit committee chair. It should also involve meetings with the CEO, members of the financial leadership team, internal audit, and external audit.

| Area | Key orientation topics |

| Financial reporting |

|

| Risk and compliance |

|

| Risk and compliance |

|

| Support and resources |

|

Continuing education is important for all board members. And it is particularly important to the audit committee given changing accounting and regulatory standards. Boards should consider a mix of in-boardroom education sessions with internal and external speakers as well as external training and events.

| Many chairs will visit global locations with the CFO to meet with local management and regulators. This allows the chair to understand local issues and regulatory requirements and provides them insight into the strength of the local team. |

| Onboarding—using the audit committee

Consider having new board members attend an audit committee meeting as observers—even if they are not joining the committee. Hearing about core audit committee agenda items (e.g., risk oversight, financial reporting, significant judgments, and estimates) can be highly valuable and an efficient way to educate new board members on the company. |

Making the meeting effective and efficient: practical approaches

Audit committees know they need to work hard to meet the mandate of their charter and to tackle other critical issues that may arise. How do they balance those duties with practical time constraints?

Some audit committee chairs use innovative approaches to meet mounting demands. We describe a few of those approaches below.

Agenda planning: setting the course

Without a carefully planned agenda integrated with the charter requirements, it’s hard to set an efficient course for the year. The committee may even fail to fulfill its basic duties. Some best practices include:

Designate a management liaison – The audit committee chair will need help managing the agenda-setting process, including inevitable changes throughout the year. It’s important to designate a specific person (e.g., corporate secretary, chief audit executive) to liaise with other members of management and coordinate changes to the agenda.

Comply with the charter – The audit committee charter is the starting point to plan the agenda for the year’s topics. The charter is the audit committee’s commitment to shareholders and reflects its required actions. Agenda planning needs to account for each item in the charter.

Plan the topics annually – Map out the agenda topics and time allotments, by meeting, for all scheduled meetings at the start of each year. Most topics are recurring. Make time for “deep dives” into selected topics such as the regulatory environment and income taxes. And leave room for unexpected issues that may come up during the year.

Confirm agenda topics before each meeting – A critical step is for the audit committee chair to touch base with other committee members, management, and the external auditors before the agenda is distributed. The chair can then make adjustments to topics or change the order and/or allocation of time.

| Agenda planning tools

Often, audit committees use agenda planning tools to help chart and monitor meeting topics for the year. They also help ensure that the committee is meeting all of its charter requirements. (See a sample agenda planning tool in Appendix A). |

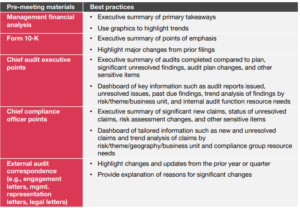

Pre-meeting materials: getting to the point

Many directors tell us that that there is room to improve board materials. They want more management insights, better-highlighted risks, and shorter and more summarized materials.

For audit committees, effective pre-meeting materials are critical given the volume of materials required for oversight. Some best practices are:

Agree on timing – Committee members need to have time to review and digest the materials. Usually, management strives to have materials available at least a week in advance of the meeting. A shorter lead time may be appropriate for telephonic meetings with limited agendas, such as those covering quarterly earnings releases. With the common use of board portals, a best practice is to post materials to the portal as they are available but make sure deadlines are clear for the most critical topics.

Use executive summaries and dashboards – Audit committee members often experience information overload. A good executive summary for each section of the pre-read materials and the use of dashboards which capture meaningful data and trends, can help. Astute committees establish a protocol with management so written materials get to the point up front and the appropriate level of supporting content follows. Common points for impactful executive summaries are:

- Why the topic is on the agenda

- Management’s insights and conclusion

- Key takeaways

- Action steps (e.g., committee vote) and timeline

Highlight changes – Reviewing a high volume of filings and reports can be challenging. Many of the recurring reports use nearly identical verbiage, making it difficult to know what is new or different. Request that management highlight substantive changes from the prior quarter in these reports (e.g., SEC filings, management representation letters from external auditors). This allows the audit committee member to focus on the underlying reason for the changes, particularly when the change was unexpected.

Use appendices – Different committee members may want different levels of detail in the materials. Focusing on the core content and including the “nice to have” detail in an appendix can make the materials more concise and focused, while not short-changing those who want to read more. It is important for all committee members to agree on the level of detail to be included in appendices. Also, committee members may want to consult the company’s legal team to understand their obligation, if any, to review supplemental information provided in appendices.

Examples of best practices for pre-meeting materials

Final preparations: the meetings before the meeting

As audit committee chair, final preparation before the meeting is critical in order to lead an effective and efficient meeting. After reading the pre-meeting materials, a series of touch points with those integrally involved in the upcoming audit committee meeting (most likely the CFO, controller, chief audit executive and external auditor) is key to being prepared.

What are the objectives of these meetings?

- Build relationships

- Get clarification of the pre-meeting materials and provide feedback

- Provide guidance on points to emphasize during the presentation at the upcoming meeting and thoughts on how to stay within the allotted time

- Alert individuals to potential questions and challenges from committee members

Overall, these meetings are intended to ensure all participants are well prepared without making the meeting overly scripted.

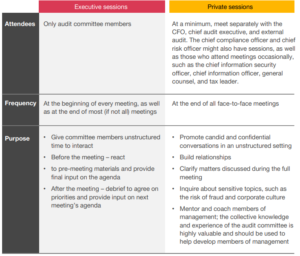

Executive and private sessions: enhancing communication

Used properly, executive sessions and private sessions are tools that are critical to the effective functioning of the committee. Many committees do not take full advantage of these sessions. Here are some best practices for each:

Executive and private session best practices

One last point on executive and private sessions: resist the temptation to make a “game-time” decision to skip them when meetings are running long. They are critical to audit committee oversight (and they don’t need to take up a lot of time).

Assessments: making the audit committee better

An annual assessment process should go beyond the minimum stock exchange requirements and be a mechanism to help a good audit committee become great. Individual members can give and receive specific feedback and development points. Assessments can help ensure that the committee is functioning well and finding ways to improve. Committees that participate in frank discussions about their performance and their composition and then commit to acting on results of their self-assessments will naturally stay sharp.

For more on the importance of assessments, read Getting real value from board assessments: Beyond “check the box”. For a checklist of responsibilities and related practical insights for the audit committee, read our Audit committee oversight checklist paper.

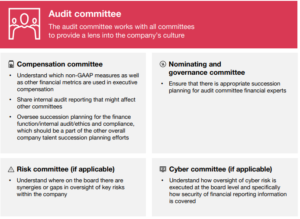

Committee connection:

How does the audit committee work with other committees of the board?

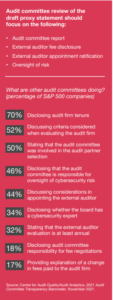

Enhanced proxy disclosures: taking credit for what you do

Audit committees often take pride in their diligent and thorough oversight. Audit committees are required to make certain disclosures in a company’s annual proxy statement, but investors and other stakeholders don’t always understand the extent of the committee’s efforts. Increasingly, investors are calling for audit committees to voluntarily enhance their proxy disclosures. By describing what the committee does in more detail, the company gives investors better insight. Investors, in turn, are in a better position to make informed voting and investment decisions.

Refer to the call-out on this page for more information on what other boards are disclosing.

When reviewing the proxy statement, we encourage audit committees to evaluate the usefulness and transparency of disclosures and consider enhancing them to respond to what investors are asking for. To get started:

- Ask those who prepare the proxy statement to draft sample enhanced disclosures,

- Benchmark proxy disclosures of peers and competitors, and

- Review proxy disclosures of companies that have already embraced enhanced disclosures.

Armed with this information, the audit committee can take a critical look at its past disclosures and decide whether to revise them.

| Having a strong audit committee chair in place is the cornerstone of an audit committee. Coupled with the right composition of members and sound approaches to tackling a demanding workload, the audit committee is destined to be high performing, effective, and efficient. |

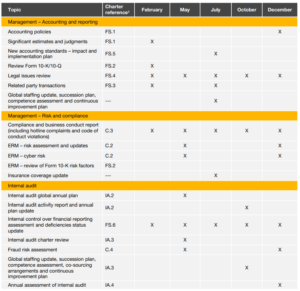

Appendix A

Sample audit committee meeting agenda planner

Table excludes quarterly meetings related to earnings releases and Form 10-Q SEC filings. These meetings are often telephonic with limited agenda topics. Some committees have expanded these telephonic meetings to add an agenda item or two to help relieve time pressure from other meetings with full agendas.

1. It is helpful to refer to specific sections of the Audit Committee Charter. A separate analysis should be done to ensure all charter actions are addressed in the meeting planner.

2. Special topics and deep-dive areas are at the discretion of the audit committee based upon current events and risks. Typically, these are not required to be addressed each year.

Appendix B

Key tips for the audit committee in deterring fraud

- Use the audit committee agenda to signal the importance of ethics, culture, and tone to senior management—and influence their behavior. Allocating meaningful time and focus to discussing the topic at audit committee or board meetings sends a strong message to executives that the committee is paying attention.

- Look beyond the tone at the top to the “mood in the middle” and the “buzz at the bottom.” Discussions with a broader group of employees across divisions or offices can give audit committee members a different perspective on tone at the company.

- Pay close attention to how executives interact with directors, both inside and outside the boardroom. Executives’ behavior can say a lot about the company’s tone at the top.

- Spend time with groups in the company that focus on controls and compliance (e.g., internal audit) to ensure they understand the importance of their role in the organization.

- Ask management about the tenure/rotation of CFOs and other key finance positions at international locations. Often, a “fresh set of financial eyes” can highlight potential problems.

- Meet regularly with the company’s general counsel and chief compliance officer to monitor compliance with legal and regulatory requirements and oversee an annual review of the company’s compliance programs and reporting systems.

- Focus on the accounting areas that require a great deal of management estimation and judgment.

- Question the rationale for any use of third parties acting as intermediaries between the company and other businesses or government organizations in territories with a high risk of fraud and corruption.

- Understand management’s process for reviewing third-party contracts and policies, including during acquisitions.

- Understand whether the company has adopted a supplier/distributor code of conduct. And whether “right to audit” provisions are included in third-party contracts and being exercised.

- Understand how the company’s fraud and cyber risk management programs are aligned and how the two work together.

- Understand the measures management takes to educate employees about insider trading risks and how they monitor activity for any suspicious trades.

Print

Print