Lawrence A. Cunningham is Special Counsel at Mayer Brown LLP, Principal of the Quality Shareholders Group and Henry St. George Tucker III Professor Emeritus at George Washington University. The following post is based on Professor Cunningham’s address delivered as the 37th Annual Francis G. Pileggi Distinguished Lecture in Law at Delaware Law School on February 10, 2023. This post is part of the Delaware law series; links to other posts in the series are available here.

The stated purpose of the Pileggi Lecture is to create an opportunity for those “distinguished” in corporate law and governance to address those “most responsible for shaping it:” the Delaware bench and bar. The message I’d like to share is: you are doing an excellent job, and please keep it up. A few takeaways upfront:

- I concur with the widely held view that Delaware’s corporate law is a national treasure

- evidence shows that Delaware’s “made-to-measure” approach to corporate governance is supported by America’s most patient and focused investors—called “quality shareholders”

- there’s reason for great skepticism about the trend toward “one-size-fits-all” governance favored by America’s indexing investor community and to resist efforts by certain shareholders to rule corporate boardrooms.

In this lecture, after summarizing the “Delaware way,” I present my research on shareholder typologies, then canvas core topics in corporate governance today along with current debates about corporate purpose. The review shows not only the soundness of the Delaware approach but Delaware’s critical role in maintaining the boundaries to protect it.

The Delaware Way and Divergent Trends

For nearly a century, every law student across the United States taking the Corporations course has learned the “Delaware way.”

Delaware corporate law envisions distinct, coordinated roles within a corporation. Shareholders elect the board. The board oversees the corporation, chiefly by appointing, directing and supervising managers, as well as shaping business strategy.

The Delaware General Corporation Law (DGCL) has some mandatory terms. But it is mostly an enabling statute offering alternatives. Specific items must be set forth in the charter, which can be amended only jointly by the board and shareholders, and others in the bylaws, which can be amended by the shareholders alone and, if the company wishes, by the board. Almost all governance provisions can be tailored to suit the needs of an individual company.

Delaware decisional law is principles based, equitable and sophisticated, with doctrinal prisms, presumptions, and shifting burdens of proof. Almost all board decisions receive judicial deference, under the business judgment rule. Some decisions, mainly those involving conflicts of interest or changes of control, are given heightened scrutiny to ensure fairness to shareholders.

In short, Delaware corporate law is enabling, deferential, and aims to protect the shareholders. It defines the norm in corporate governance as recognizing differences among companies—the need to tailor governance to fit. Traditionally, shareholders have concurred in this structure.

In recent years, however, some express a divergent philosophy: one-size-fits-all. They prefer a universal and prescriptive governance formula. They also veer into the board room, issuing “expectations” of what directors and companies should be doing in a host of areas, from the workforce and customer markets to community impact.

This cohort prescribes a single set of requirements in both corporate governance and behavior. A common argument for favored policies is: “everyone else is doing it, you should too.” I’ve repeatedly heard that argument myself in my professional capacities.

But the cohort I hear it from the most is my children. And as I remind my kids, the argument is specious. It’s never a good idea for kids to cave to peer pressure and thoughtlessly follow the crowd. It’s even more dangerous for institutions such as corporations to fall for that fallacy of social proof.

All this has made me wonder, why? Why this genuflection to one-size-fits-all? Why this divergence from the Delaware way? I found answers in the study of shareholder demographics. I’ll first present some illuminating research on shareholder typologies, then turn to specific corporate topics.

Shareholder Typologies

Shareholders are not monolithic. They vary widely based on many characteristics. They have different time horizons and degrees of concentration. They may be deferential or antagonistic to management. Companies have long tried to cultivate their shareholder base accordingly.

A classic analogy appears in the 1958 book by stock picker Phil Fisher, Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits. The famed investor likened companies to restaurants. Each offers a menu attracting a given clientele. Five-star cuisine attracts gourmands, fast food catches eaters on the run, and buffets draw an indiscriminate crowd.

From his start in the late 1970s, Berkshire Hathaway’s Warren Buffett took Fisher’s advice. Through shareholder letters, annual meetings, and company policy, he tried to attract what he called “high quality shareholders,” those who see themselves not merely as shareholders, but as business owners. They are focused and long-term.

These insights inspired others, starting with CEOs, to appreciate the value of having patient and interested owners, not fleeting or distracted ones.

Advisors reinforce this message. Consultants at McKinsey, as well as many investor relation firms, stress how long-term focused shareholders are patient through short-term adversity. Proxy solicitors and raid defense firms stress the quality shareholders’ willingness to focus on company-specific details.

Among scholars, Harvard’s Michael Porter was one of the first researchers to explore the topic. He explained why, in the 1980s, German and Japanese companies were more productive than US counterparts, due to shareholder demographics: US investors had moved towards indexing and trading, not being concentrated or patient, and that impaired corporate performance.

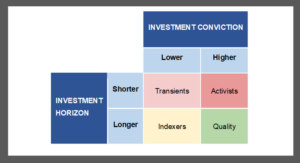

In the 1990s and early aughts, Wharton’s Brian Bushee enlarged and formalized Porter’s insights to classify shareholders by type, which he thought might be useful for future study of shareholder behavior. In pioneering research that’s been widely used, Bushee focused on two variables: time horizon (measured by holding periods) and conviction (measured by portfolio concentration).

In the past decade, Martijn Cremers of Notre Dame has explored how funds managed by active quality shareholders outperform those operated as passive index funds.

Scholars in both finance and law use this research for many studies, from assessing alternative shareholder voting regimes to dissecting the role and types of shareholder activists, both economic activists and policy activists.

I’ve written a book and four research articles on this topic, plus many columns; conducted empirical tests and research surveys of governance practices and preferences; and founded and run a university research center and a boutique consultancy firm.

To summarize visually, shareholder cohorts can be classified in this 2×2 graph

Looking at the investment landscape today, indexers dominate. Though popular only since the 1980s, index funds now hold as much as 40% of public equity.

The indexing cohort are ruled by the big three—BlackRock, State Street and Vanguard—which together control as much as 20% of many large companies. Other indexers rely on the two powerful proxy advisors, ISS and Glass Lewis.

Transients, following the ancient practice of holding stocks for short periods, are also numerous. They reach from 25% to 40% of total public equity, depending on your time cutoff defining short-term. Many use nanotechnology and artificial intelligence to guide trading decisions, which can increase short-term trading.

Activists are a small but powerful cohort, and increasingly diverse: some focus on traditional shareholder value while others campaign for social or political agendas by using the rights of share ownership.

Quality shareholders make up the rest. They are united by patience, conviction, and a contextual approach to corporate governance and administration.

While Warren Buffett is an exemplar, he credits his Columbia Business School professor, Ben Graham, who taught students to focus on particular companies not market aggregates. The two have influenced millions of investors over several generations. They form a professional subset with their own canonical books, professional associations and designations such as the CFA.

All shareholder cohorts contribute something but also present downsides. Index funds enable millions to enjoy market returns at low cost but may allocate limited resources or capacity to understand specific company details.

At a typical large index fund, 45 staffers cover 3,000 companies, posing tens of thousands of governance questions every year. Proxy advisors also operate on shoestring budgets, around 1,000 people making recommendations on 100,000 questions annually.

Index funds are concerned most with the performance and size of a portfolio, not specific companies. They therefore have an incentive to prescribe policies expected to benefit the overall stock market on average, not particular companies.

Transients offer liquidity but may add volatility. And compressed shareholder time horizons can induce a short-term managerial view.

Activists focused on shareholder value promote accountability, but some may get carried away occasionally, while policy activists use shareholder rights to advance social or political goals.

Quality shareholders offset these downsides: they are concerned almost entirely with specific companies, consciously ignore short-term adversity, and tend to prefer quiet engagement focused on shareholder value. The chief downside of quality shareholders is that they can be wrong in their judgments.

Governance

With that research framework, let’s compare philosophies and approaches to corporate governance. To begin, start with two cautionary statements about corporate governance: (1) pat formulas should be viewed with great skepticism and (2) drastic reform suggestions should simply be opposed.

These appear to be credible reflections of the Delaware philosophy of corporate governance, acknowledging that pat formulas are suspect because one-size does not fit-all and drastic reforms are dangerous as they tend to overshoot targets and destroy value.

The cautions could have been written today—by me, no less. But they were written 40 years ago by a legendary Delaware lawyer, Irving Shapiro. His 1984 book, America’s Third Revolution, has a thorough chapter on corporate governance, weighing age-old debates.

Irv gave me a signed my copy of his book when published, which I still open from time to time and am ever grateful for his wisdom. I remember how astute his warnings were then and marvel at how apt they remain today. After all, pat formulas and drastic proposals are everywhere in corporate governance nowadays.

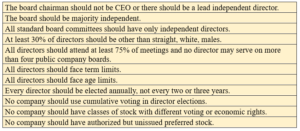

Starting with the pat formula, consider this 11-pronged approach reflecting a prevailing philosophy of the indexing community.

The list is extracted from BlackRock’s guidelines for the 2023 proxy season, which it outlined last month in a post on Harvard Law’s governance blog. The giant indexer, and others in its cohort, including the proxy advisors, publish such guidelines every year. I’ve long studied them, and they seem to get more prescriptive and pat with each edition.

They contain many more items, but these illustrate the style. They present sharp bright line rules—for independence, diversity, and terms of office—plus clear singular preferences on numerous governance choices. While the firms disclaim that these preferences are inviolate rules, saying they examine many topics “case-by-case,” in practice, they take that form.

Compare the BlackRock rules with the Delaware philosophy and approach. Under the DGCL, every one of these provisions can be tailored for a company and all are authorized to go either way. Delaware case law has no general rules or restrictions. Rather, it points to the required fiduciary duties: the duty of loyalty, where independence is relevant, and care, where being fully informed is required.

The Delaware approach is how quality shareholders prefer it. For every element on the BlackRock list, empirical data and survey results show that quality shareholders disagree with the prescription. They prefer to focus on particular company choices, viewed in context.

According to my research, what quality shareholders seek most in directors is business savvy, interest in the particular company and an appreciation of shareholders as the owners of a business. Independence or diversity may be factors, but quality shareholders don’t like fixed percentages and don’t put those factors above a shareholder orientation.

To illustrate, take the first topic listed, of splitting or combining the chair and CEO role. Quality shareholders are just as likely to own large stakes in companies that split these functions as combine them. They understand that in some cases the chair-CEO roles should be split, in other cases combined.

On this and all these topics, empirical research on their relation to corporate performance shows there’s no single right or wrong answer. The only answer is “it depends.”

For example, research shows little if any relationship between director independence and corporate performance. To the contrary, a board’s independence appears to be less important than its active engagement.

Indexers tout evidence of correlations between formula elements and corporate performance, such as board diversity. Yet there’s scant evidence that any of these elements is the cause of better performance.

Publishing prescriptions like these poses another problem: choices at first innocently called “best practices” have a way of hardening, making departures taboo. Stark examples to date include the inexorable rise of independent directors and the abolition of staggered boards.

While prescribed practices are desirable for some or many companies, they aren’t best for all companies. In that way, the contextual approach inspired by Delaware, preferred by quality shareholders, is superior to formulaic governance favored by indexers.

The E and S in ESG

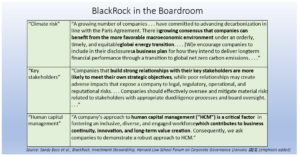

Looking at other topics high on the agenda of indexers—the E and the S in ESG—indexers increasingly assert strong opinions and direct the same actions of all boards on many topics. For instance, in the same document released last month, BlackRock, like other indexers, calls for behavior and details on climate risk, key stakeholders, human capital, natural resources, succession planning, and other topics.

How to address such weighty matters varies by company, for boards to resolve. Yet BlackRock advises ALL corporate boards that:

- there’s a “growing consensus” that companies benefit from a particular energy transition and need a related business plan;

- they should “build strong relationships with key stakeholders” because that helps meet other objectives; and

- human capital management is a “critical factor” that “contributes to business continuity, innovation and long-term value creation.”

Topics raised in such guidance are important for society, and policy activists increasingly use shareholder rights to pressure companies to pursue related agendas. But a corporation’s role in addressing such topics is contestable and variable.

From a director’s perspective, all the assertions are mere opinion and each suffers other flaws, especially being one-size-fits-all as well as speculative, presumptuous, acontextual and unnuanced.

Under Delaware law, it’s for directors of a particular company to determine, under the protections of the business judgment rule, whether a “growing consensus” exists on a topic, whether to join or challenge that consensus and whether a corresponding business plan is necessary or appropriate.

As the Delaware Supreme Court noted in Brehm v. Eisner, it’s also for directors, not shareholders, to determine whether to follow governance practices seen as “good,” “desirable” or “beneficial.” As emphasized in cases such as Caremark and Stone v. Ritter, evaluating fiduciary oversight obligations requires context, pivoting on questions of “good faith” and “reasonableness,” not a one-size-fits-all affair.

The SEC

Federal securities regulators are inclined not only to pat formulas, but to incursions into corporate governance that’s long been the province of state law. Influenced by the indexing community and other advocates, the regulators are pursuing a one-size and intrusive approach to corporate governance.

Prominent examples appear in the SEC’s proposed regulations on cybersecurity and on climate change. Both call for detailed information about a company’s related risks, potentially relevant to the SEC’s statutory mandate over national securities markets and investor protection.

But both also intrude into board governance and practices. They would require details on board responsibilities and expertise in these subjects, how the board processes related information, how often directors discuss these topics, and how boards relate these topics to other corporate affairs.

Delaware imposes no such specific requirements or blueprints. It relies instead upon general standards of fiduciary duty that recognize context. They let different boards operate according to the best interests of their corporations—all with deference under the business judgment rule.

Such unitary intrusions, from both federal regulators and indexers, probably qualify as “pat formulas” warranting “great skepticism,” as Irv Shapiro advised. They also approach “drastic reform suggestions” that he advised opposing “in toto.”

Social

For a clearer example of both pat and drastic, consider pressure to compel companies to issue mission statements emphasizing a social dimension and demands that CEOs speak out on social issues. Infamous for exerting such pressure is again BlackRock, through its CEO, Larry Fink. He writes an annual open letter to America’s CEOs telling them how they and their boards must behave. A sampling of these controversial but influential missives:

- amplifying earlier calls for “mission statements,” Fink’s 2018 letter says boards must review and companies must publicize a written strategic framework which must show an understanding of the company’s societal impact.

- 2019: companies must demonstrate their commitment to communities where they operate on issues “central to the world’s future prosperity.”

- 2020: after prescribing extensive “sustainability” disclosure, noting that BlackRock doesn’t support directors of companies lacking such disclosure—pointing to “4800 directors at 2700 companies”

- 2022: CEOs must speak publicly on where they “stand on societal issues”

But nothing in law, business or logic requires companies to adopt any such written statements or frameworks, let alone ones like that, or for CEOs to take any such public positions.

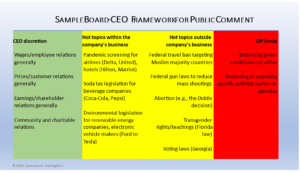

To the contrary, it’s up to individual CEOs and boards to determine whether and how a company might speak on “societal issues.” Many may wisely determine it’s in their company’s best interests not to do so. Recent boardroom debacles at Disney show the dangers in this area warranting attention to context.

Rather than one-size-fits-all, each board and CEO determines what’s in the best interests of their company and its shareholders. They might use a general framework, such as that I suggest below, to name topics the CEO is authorized to speak freely on (such as wages or employee relations) and others that are off limits (such as endorsing candidates for public office) while deciding others according to their relevance to the corporation’s business.

Turning to the call for mission statements, Fink expects every company to have one and all to stress social aspects. But this ignores the great diversity of opinion about the utility and appropriate scope of corporate mission statements.

Some business leaders swear by corporate credos as guides to behavior. But many worry that they freeze a culture, stunting healthy evolution. Still others note that words are cheap, and many mission statements ring hollow.

Enron, that fantastic fraud, had a mission statement boasting the loftiest values, including respect for others under the Golden rule, and integrity comprised of being open, honest and sincere.

Other companies historically adopting mission statements have expressed a range of priorities. These span from a commitment to dedicated stewardship of shareholder capital at Berkshire Hathaway to saving the earth at Patagonia and the concept of “performance with a purpose” at PepsiCo.

Perhaps the most famous is that of Johnson & Johnson, dating to 1943, noted for the hierarchy of its priorities: customers; employees; communities; and then stockholders. The philosophy reflects a commonsense view of business long associated with Ben Franklin, doing well by doing good: doing good by the other constituencies is the path to doing well for shareholders.

In response to the new demands for mission statements tied to social interests, many companies copied the J&J credo. In 2019, the Business Roundtable did so in one fell swoop. Nearly 200 CEOs embraced the J&J credo, as a trade group. They said their individual companies served their own corporate purpose, but all shared the “fundamental commitment to all stakeholders.”

Aside from a one-size-fits-all mission statement for nearly 200 corporations, the associated fanfare sparked fresh conversations on an old topic: whether a for-profit corporation’s purpose is primarily to benefit shareholders, other stakeholders, or some combination.

Extremists paint a stark choice—akin to pitting Karl Marx against Adam Smith: some oppose any form of shareholder primacy while others oppose any balancing of contending interests. But many seem to agree with the tradition that lies behind J&J’s original intention dating to Franklin and repeated in by Shapiro in America’s Third Revolution.

Such an approach reflects Delaware corporate law, which is both constraining and liberating. The director’s fiduciary duties of care and loyalty require acting in the best interests of the corporation and its shareholders.

That accommodates, but does not elevate, the interests of other constituents. It facilitates a practical middle ground where companies invariably operate. After all, companies don’t sacrifice employee interests to add pennies to profits, but nor do they continue staffing operations showing endless losses.

While many in the ESG movement earnestly believe that its agenda promotes shareholder interests, there are those who would repudiate the shareholder interest in favor of environmental causes and social justice achievements. Policy activists often do just that by becoming shareholders and exercising related rights.

The SEC, again wading into state law prerogatives, is helping them by loosening the shareholder proposal rule. Historically, companies could omit shareholder proposals pushing broad social policy agendas unrelated to a company’s business. But since last year, anything having to do with society must go on the ballot. The SEC staff says it will disregard “the nexus between a policy issue and the company” and instead focus on “the social policy significance of the issue” raised in the proposal.

Old Tensions and the Delaware Guardrail

We’ve seen variations on such tensions throughout modern corporate history:

- the famous Berle-Dodd debate of the 1930s asked whether corporations are primarily economic or social institutions.

- tensions throughout the 1960s and 70s mooted the relative merits of markets versus regulation, with polar positions represented by Milton Friedman and Ralph Nader.

- in the 1970s and 80s scholars debated whether corporations should continue to be chartered by states or have federal law preempt them—SEC chair Bill Cary arguing for preempting Delaware with Judge Ralph Winter defending the states.

A recurrent pattern appears: related movements usually achieve gains—and then face setbacks and a return to a more centrist position. For example, during the takeover fights of the 1980s, many of which played out here in Delaware, raiders stressed “shareholder value,” while embattled targets lobbied to consider “other constituencies,” especially employees and communities.

The constituencies movement became powerful. Many states passed “constituency statutes”—although not Delaware. But by ultimately trying to put the interests of such constituents ahead of the rights of shareholders, advocates overplayed their hand and lost the cause.

Amid those tensions, the Delaware Supreme Court contributed pivotal, pragmatic, clarity. It stressed that directors may consider such other interests, but only if those are “rationally related to shareholder interests,” which held priority. Justice Moore’s landmark Revlon opinion was a guardrail against activism veering off the track.

Today, all those tensions are back and rising. Proponents of the social and stakeholder conceptions of the corporation are raising the temperature and opponents are stoking a widely publicized backlash.

Amid such debates, it’s easy to imagine cases reaching Delaware courts, if they haven’t already.

ESG in Delaware

Coming issues might include the role of shareholder views on one-size-fits-all best practices, the Caremark duty of oversight spanning spheres from climate to the workforce, or a board decision starkly trading shareholder interests for environmental or social priorities.

Today, boards and shareholders enjoy wide freedom to define governance, but boundaries remain. While Delaware corporate law almost never prescribes governance arrangements or “blueprints” for board action, it continues to provide important and necessary guardrails, anchored in the Delaware way.

I’ll conclude by paraphrasing Irv Shapiro again—in words that are as true today as when he wrote.

The chief reason that Delaware is a popular place to be incorporated. . . is that Delaware has a legal code that is modern and fair, and that is kept up to date . . . . Delaware judges [inspire] confidence in the stability and wisdom of the Delaware courts.

What Delaware does not do to or for corporations, however, is to use charters as instruments for telling companies who ought to be on their boards or what the qualifications for directors should be. Nor does the state seek to use charters as weapons for regulating companies in new ways.

Shareholder demographics change, along with fashions in the philosophy of corporate governance. But the DGCL’s appeal, and the Delaware judiciary’s inspiring leadership, are enduring. Please keep up the good work, Delaware, whatever comes down the docket, as the country, not least its quality shareholders, are counting on you.

Print

Print