Jordi Canals is Professor of Strategic Management and the holder of Fundación IESE Chair in Corporate Governance at IESE Business School. This post is based on his book.

Disney’s board of directors fired CEO Bob Chapek on November 20, 2022. He was nominated for that job in February 2020 to replace Bob Iger -Disney CEO between 2005 and 2020-, after several board attempts in previous years to speed up Iger’s succession. The board brought back Iger as Disney CEO to replace Chapek in November 2020. Disney’s board was facing complex strategic challenges that included, among others, the weak performance of Disney+ -the streaming business launched in 2019-, a falling share price, technology disruption threatening its core business, unsustainable debt levels, and the rising geopolitical risk in China. On top of this, Disney was facing a growing pressure from activist investor Nelson Peltz, whose Trian Fund had amassed a position close to 2 per cent of outstanding Disney equity by October 2023. Disney’s board daunting problems show how the combination of technology disruption, growing competition in business models and platforms, activist pressure, geopolitical risks, and the CEO succession process present a formidable challenge for the most competent boards.

Over the past two decades, a guiding idea of institutional investors and capital markets regulators in the US and the EU was that board structure and composition, and board directors’ professional expertise and diversity, were features that would improve board effectiveness. There is a growing perception in academia and the business world today that the current model of boards of directors based on a majority of independent board members, the separation of the chair and CEO jobs, active board committees and stronger compliance is not effective to help govern companies in times of complex disruptions. The recent cascade of corporate crises involving companies whose boards shared those positive features (such as Credit Suisse, Danone, GE, GSK, Wells Fargo and WeWork, among others) has opened up the discussion on how to improve the board model and develop better corporate governance.

In my new book, Boards of Directors in Disruptive Times (Cambridge University Press 2023, Boards of Directors in Disruptive Times (cambridge.org)), I present a model of boards that offers a holistic view of its functions in times of rapid change. It discusses the value of some board’s structural features -such as the positive role of competent, independent board members-, but goes beyond structural characteristics to consider how boards can grapple complex strategic issues, work as effective teams, and help create value.

The empirical evidence used in the book includes detailed clinical studies of 11 companies and 78 personal interviews with their CEOs, board members and senior managers. The emerging data is organized in a framework that highlights the main functions that boards may develop to help firms tackle disruptive challenges effectively and support corporate strategies that drive value creation.

The evidence presented suggests that effective boards need to think beyond board structure, monitoring, and compliance. A coherent strategy, a unique business model and execution are drivers of economic value (see M.E. Porter, 1996, What Is Strategy? (hbr.org)). There is abundant empirical evidence -that is also supported by the clinical studies presented in this book- that suggests that good strategic thinking and effective execution require an organization with competent people, good management, a collaborative corporate culture, effective leadership development and a sense of accountability and performance. These factors help companies create value sustainably. The relevance of these areas suggests that the board should work on these tasks in collaboration with the CEO.

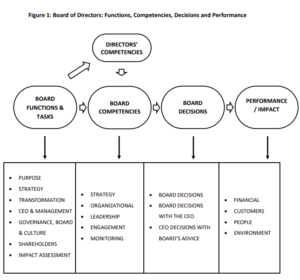

Boards need to develop unique capabilities to undertake these critical functions effectively. The board is a team made up of diverse individuals. The current emphasis on individual directors’ competencies is positive, but the board itself should work as a collegial team and develop as a team the competencies to govern the firm and tackle its main challenges. A better quality of boards’ competencies can help improve the quality of the board’s decision-making -for instance, the appointment of a new CEO or the approval of a major acquisition- or the quality of the board’s advisory function to the CEO -on issues such as leadership development, business model or commercial policies. Figure 1 presents the logic behind the notion of boards of directors’ functions competencies and their relationship with performance (see Figure 1).

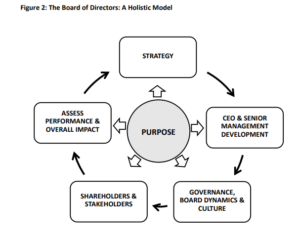

The model of the board of directors presented in this book is structured around six critical board functions that support long-term value creation: discuss and adopt a corporate purpose; establish the firm’s long-term orientation through a unique strategy; appoint, support and assess the CEO and the management team, and prepare credible succession plans; develop a quality corporate governance model that includes an effective board; engage effectively shareholders and critical stakeholders; monitor performance and assess the firm’s overall impact (see Figure 2). The evidence suggests that the board as a team should develop strategic, organizational, leadership, engagement, and monitoring competencies. The experience of the boards reviewed in this book confirms that essential board competencies are shaped by the board’s main functions. Both board critical functions and competencies present some company-specific varieties.

The first board’s critical function is to debate and adopt the firm’s purpose, and eventually get shareholders’ approval. Firms are relevant social institutions that may have a purpose, as well as explicit goals to achieve. The board should understand and discuss why its firm exists and define in cooperation with the CEO the specific customers’ needs the firm wants to serve in a profitable and sustainable way (see C.Mayer, 2018, Prosperity – Hardback – Colin Mayer – Oxford University Press (oup.com), ). It should make sure that shareholders support it (see L. A. Bebchuk and R. Tallarita, 2020 The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance – Cornell Law Review). Profits are a condition of success and survival but are not the specific purpose of a company (see A. Edmans, 2020, Grow the Pie (cambridge.org))

Defining and nurturing a corporate purpose is a proven pathway to develop a healthy culture; foster strategic thinking, customer loyalty and employee development (G. Serafeim, A. Prat and C. Gartenberg, 2019 Corporate Purpose and Financial Performance | Organization Science (informs.org)); establish boundaries on what to do and what not to do; structure key strategic decisions; and manage diverse shareholders’ expectations. A clear purpose facilitates better communication between the firm and its customers. It helps investors understand the type of company they invest in. Adopting a purpose goes beyond a statement of purpose. As the companies examined in this book show, purpose can be an effective engine that helps create value when it is implemented well, which requires a careful integration of purpose with corporate strategy, business model and key corporate policies. In this way, purpose interacts with key policies and decisions and it is natural that the board oversees this process.

The second critical board function is to debate and approve the company’s strategy that can help create value sustainably (G. Gavetti and J. Rivkin, 2007, On the Origin of Strategy: Action and Cognition over Time | Organization Science (informs.org) ). Board members should encourage long-term thinking, discuss the company’s strategy and business model with the top management team, and set an aspiration for the type of company that it wants to be.

The board’s job is not to replace the senior management team in this function, but work collaboratively with the CEO on corporate strategy. It should first understand the industry in which the company operates, its customers and competitors; work with the CEO and her team to check assumptions by asking the right questions, help think about scenarios, and debate goals and policies. By considering the firm’s challenges and strategic options, and defining mechanisms to track execution, the board will be a better partner to help create value (see A.M. Brandenburger and H. V. Stuart, 1996, Value‐based Business Strategy – Brandenburger – 1996 – Journal of Economics & Management Strategy – Wiley Online Library

Strategy is not static. It involves dynamism. When market conditions change or disruptions emerge, the board should challenge the senior management team on whether the firm should change its strategy. Corporate change and transformation used to be processes that companies undertook occasionally. Amid the current disruptive climate in the business world, companies need to change tack more often, and boards need to help the CEO in steering the course needed for the firm’s survival.

The third key board function is the CEO and senior managers’ appointment, development, compensation, and succession. The choice of a new CEO is one of the most consequential decisions that a board can adopt (See J.L. Bower, 2008 The CEO Within: Why Inside Outsiders. It is also one of the most complex ones. Choosing the wrong CEO is also a prime reason why many companies get into trouble As with strategy, individual board members may have experience in appointing a CEO but it is not the most common type of expertise. A CEO successful appointment process is also related to leadership development in the company (See P. Cappelli and J.R. Keller, 2014 Talent Management: Conceptual Approaches and Practical Challenges (annualreviews.org)). This is a key area the board should pay attention to. In the end, senior leadership development is closely connected with the firm’s people development policies. Successful strategy and transformation processes depend very much on their interaction with effective leadership development and boards should help management invest in people to boost performance, and oversee this process.

The fourth board function is to define the firm’s corporate governance rules and seek shareholders´ approval. These rules can contribute to develop better governance and management and generate trust inside and outside the company. A clear definition of the board structure, composition, capabilities and responsibilities, as well as the conditions for positive board dynamics, are good steps towards improving the quality of board governance. The board should pay attention to these dimensions, as well as to the human and interpersonal dimensions of companies.

Investors and regulators are increasingly concerned about how the board of directors monitor and shape the firm’s culture and boards should spend time working on these critical dimensions. Corporate culture can have an impact on setting goals, defining corporate strategy, and designing executive compensation schemes (A. Guiso, P. Sapienza and L. Zingales, 2015 Corporate Culture, Societal Culture, and Institutions on JSTOR). Culture is the responsibility of the CEO and the senior management team. Nevertheless, culture’s sheer importance means that the board needs to understand, assess, and oversee it. Boards that think long-term need to move beyond compliance and promote a healthy corporate culture that encourages positive individual and corporate behavior.

Collaboration is a key ingredient of a healthy culture in any company, since organizations require coordination and trust (See B. Holmstrom and P. Milgrom, 1991 Multitask Principal–Agent Analyses: Incentive Contracts, Asset Ownership, and Job Design | The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization | Oxford Academic (oup.com). Boards should not only monitor but collaborate with the CEO. CEOs are accountable to the board of directors, but accountability and monitoring do not exclude collaboration. The board can become a team capable of working with the top management to develop the firm for the long-term.

The human reality of boards also influences board’s effectiveness (See R.S. Peterson et alia 2003, The impact of chief executive officer personality on top management team dynamics: One mechanism by which leadership affects organizational performance. (apa.org) ). The board is a group of individuals who meet only occasionally, with a part-time dedication to the company, with ambiguously defined goals and without a shared mindset beyond the duties of care and loyalty. The question of whether the board can work as an effective team is a core issue in corporate governance which has received little attention. The evidence presented in this book points out the high relevance of this factor to improve board effectiveness.

The fifth board function is an active engagement with shareholders (See D.Katelouzou and D.W.Puchniak Global Shareholder Stewardship (cambridge.org). Effective boards get shareholders’ views, listen to them, and learn from their suggestions. The board should define clear guidelines to engage with shareholders –beyond some decisions regarding dividends or other financial dimensions. The board, not shareholders, should govern the company, but shareholders have a say on the company’s critical decisions and development. Responsible shareholders should make the effort to know the company well and the board of directors should consider their concerns. The board can help develop the shareholder structure that best supports the company’s nature and purpose. The board can also provide clear guidelines on how senior managers may engage other key stakeholders in a constructive dialogue and gain their views and commitment to the long-term development of the firm.

The sixth function of the board of directors is to assess the firm’s financial performance and overall impact (See R. Simons 1997, Strategic Orientation and Top Management Attention to Control Systems on JSTOR). Monitoring performance is the board’s legal duty. Boards should disclose information following regulators’ guidelines. Moreover, a board can also explain which goals the firm pursues, how performance meets shareholders’ and key stakeholders’ expectations, and the rationale of the firm’s strategy and strategic decisions and how they support the firm’s purpose. The board should use an integrated–and simple–framework to report on the firm’s performance, including relevant financial and non-financial dimensions. In particular, the board should ensure that ESG dimensions -particularly, its environmental impact- are coherently integrated in the corporate purpose, strategy, and people development strategy. The evidence of some successful companies over the years which have taken ESG dimensions seriously shows that integrating these dimensions into the firm’s strategy is a key success factor. This is a demanding function for the board of directors, but the outcome of a more holistic view of boards involved in crafting strategy, developing people, and supporting the firm’s culture. The board should regularly assess its effectiveness in advancing the firm’s purpose and goals.

This model defines a paradigm for boards that meets their legal duties of monitoring top management and the firm’s performance. It also moves beyond these goals and delves deeper into the drivers of the firm’s performance. This model also helps consider that an effective board as a team requires to help tackle the firm’s challenges, beyond the individual directors’ capabilities.

Companies are relevant and fragile social institutions, and prosperity depends upon them. Rethinking the quality of the firm’s governance and adapting the board of directors’ model to the reality of simultaneous disruptive changes are critical. The quality of boards’ governance for companies and society is more important than ever.

Print

Print