The rapid escalation in uninsured deposit runs in March 2023 led to chaotic intervention with potentially severe fiscal implications. The runs spotlighted once again the limit on prudential norms. Since the collapse of SVB, Credit Suisse, and other smaller banks that year, many reform proposals have focused on stronger ex-ante prudential measures, such as higher capital and liquidity rules (Admati et al., 2023). Yet other proposals have included an expansion of public insurance for corporate deposits (Heider et al., 2023; Dewatripont et al., 2023). In our view, higher capital and liquidity rules would be most effective but also controversial because of their cost, while expanding insurance would also be costly and lead to more risk.

In a recent paper, we propose an alternative that focuses on the role of the supervisor (Pillar II) in prompting recovery of solvent yet undercapitalized banks through the timely activation of interim measures. Our aim is to restore credibility to timely intervention and empower the supervisory authority to prompt the recovery of viable banks.

The 2023 experience showed how supervisors failed to take timely and concrete steps to help viable banks slipped towards insolvency because the supervisors worried about triggering uncontainable runs (Cecchetti and Schoenholtz, 2023). Such regulatory forbearance buys time but leads to a steady deterioration of value and increased losses. Thus, the current regulatory framework has a major blind spot: Once a bank becomes undercapitalized, there are no credible tools to promote recovery or contain runs.

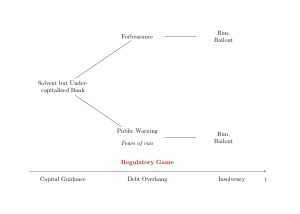

Without intervention, supervisors are left with two sub-optimal options. Current preventive tools at prevention like suspending dividend payments offer little immediate relief while sending a signal about bank losses, thus triggering a run. This gives rise to a “capital forbearance” game (Martynova et al., 2022), where a lack of credible measures leads shareholders and regulators to gamble on a recovery. Prolonged forbearance worsens capital deterioration, leading to rising fiscal losses (Figure 1).

Contingent Measures: Favoring Recovery over Resolution

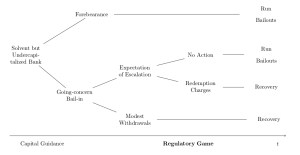

We propose two preventive measures to fill the intervention gap. The first would be an early distress measure of capital and an acute distress measure of liquidity. The second, on the capital side, would be strengthening the Pillar II mandate on the going concern loss-absorption of contingent convertible debt. These proposals would be credible only in combination with tools to contain any escalation of outflows. We propose, in effect, throwing some sand in the wheel by discouraging outflows to escalate into self-fulfilling runs. Redemption fees similar to the new rules the SEC recently adopted for prime money-market funds would be directly triggered by high daily outflows of uninsured deposits so as to act as automatic stabilizers. This is in line with market practices as money-market funds have long been the main destination for corporate cash, offering reliable liquidity and a better yield with modest price risk.

Redemption charges would eliminate the incentive to respond to outflows with withdrawals, thus directly reducing run incentives. Charges imposed quickly would also reduce expectations for further withdrawals by others, avoiding escalation driven by fear of dilution rather than solvency concerns or liquidity needs. Charges may be seen as a Pigouvian tax on withdrawals with no liquidity needs and would force withdrawing depositors to internalize the liquidity externality they cause (Perotti and Suarez, 2011). Figure 2 depicts the key nodes for a solvent but undercapitalized bank when both capital and liquidity recovery measures are in place.

A reliable stabilizing tool that discourages sudden outflows would reduce concerns that public measures would lead to an inevitable escalation. Removing the threat of a run raises the credibility of recapitalization measures and reduces forbearance incentives. Both measures represent a form of preventive, partial bail-in to preserve going-concern value for solvent intermediaries. Complementing going-concern recapitalization through contingent convertible bonds (CoCos) with redemption charges preventing runs largely addresses U.S. criticism of these instruments.

Regulatory Design and Calibration

The 2023 crises demonstrated that the lack of effective and timely interim powers to address bank distress leads to further deterioration, chaotic runs, and bailouts. However, the challenge is to design and calibrate interim tools that are both efficient and legitimate.

Many banks are currently undercapitalized because of losses on safe assets, though higher lending rates may improve future returns (Jiang et al., 2023). Such banks may be at the mercy of run expectations, as the value of their deposits and some of their assets may not be realized quickly. Such banks are the natural candidates for contingent measures aiming at recovery.

Having defined the rationale for interim intervention and having identified the key measures to maximize the probability of recovery, two key challenges remain open: legitimacy and calibration.

Legitimacy relates to instances in which the supervisor – an administrative agency – should be allotted these additional intrusive powers (Tarullo, 2022). Legitimacy is not only crucial for upholding the rule of banking law but also has also ramifications for strategic interactions between the supervisor and the banks it oversees. The supervisor will be willing to use intrusive powers only as long as they do not create disproportionate legal risks for the agency.

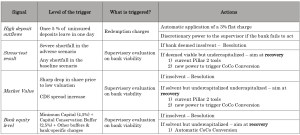

To ensure legitimacy, we propose a recovery procedure through legislation. The procedure gives the supervisor additional interim powers and should be activated only upon verifiable signals. The supervisor will be allowed to use these powers proportionately to prompt the bank’s recovery. The recovery procedure should be brief – 30 to 60 days. This would allow the supervisor to act timely without becoming a shadow director of the bank and creating legal risk for itslef. The first two columns of Table 1 summarize the relevant signals that would prompt the activation of the recovery procedure.

The procedure should also be backed by a formal commitment to provide emergency liquidity assistance (ELA) to the bank in recovery. This would strengthen the procedure’s credibility and the legitimacy of the supervisor’s intrusive powers. Our proposal has an advantage over the current practice of allowing all banks to post their assets and receive liquidity for the assets’ face value, which is a form of ELA that can easily turn into a bailout. Under our proposal, this type of emergency liquidity would be available early on to specific, distressed banks rather than to the banking system. Moreover, such emergency liquidity assistance would be conditioned on actual recovery via the interim tools discussed above.

Beyond legitimacy, the other key challenge is the calibration of the various interim measures. While a full-fledged calibration exercise would require a formal model, some basic calibration principles can be derived from theory and current practices. The right columns of Table 1 display the principles guiding the calibration of interim measures.

Unlike capital conversion, redemption charges should not be seen as a supervisory action, but as tools of a properly functioning market. They serve as automatic stabilizers, maintaining access to funds at times of illiquidity while limiting an unnecessary escalation. Charges would be triggered upon large daily outflows of uninsured deposits (more than 5 percent). This would represent a credible and actionable tool for containing run incentives.

A credible threat of conversion can pressure shareholders into taking timely corrective actions and improve the chances of bank recovery. Contingent measures complement ex ante capital and liquidity buffers and would rely less on book equity measures. They are vastly preferable to an expansion of deposit insurance for uninsured corporate deposits, which would lead to higher moral hazard and risk creation (Perotti, 2023; Martino and Vos, 2023).

Ultimately, bank run incentives can be contained by much higher buffers, just as flooding can be contained by higher dikes and levees but also, when necessary, sandbags stored as precautionary measures. In contrast, relying on deposit insurance can look like passively accepting the inevitable breach of the levees and redirecting the flooding to a larger area.

This post comes to us from professors Edoardo Martino and Enrico Perotti at the University of Amsterdam. It is based on their recent article, “Containing runs on solvent banks: Prioritising recovery over resolution,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog