Andrew Metrick is the Janet L. Yellen Professor of Finance and Management at the Yale School of Management and the Director of the Yale Program on Financial Stability; and Paul Schmelzing is an Assistant Professor of Finance at Boston College and a Research Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. This post is based on their recent paper.

In March 2023, the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) shocked global financial markets. In many ways, the SVB failure was a classic bank run, with details that appear drawn from the 19th century rather than the 21st. With a deposit base more than 90% uninsured and a balance sheet badly damaged by a combination of bad luck and bad strategy, SVB could not be saved by the standard tools of the Federal Reserve and FDIC. Instead, the FDIC was forced to take the unusual step of a takeover during business hours, with many details of this resolution not released until the next weekend. These events began a series of bank interventions on both sides of the Atlantic that is still ongoing as of this writing. A long-horizon view through the prism of intervention patterns can allow for the identification of a “systemic” banking crisis long before the macroeconomic data of that period is complete; in this case the combination and size of interventions in March 2023 strongly suggest that we are already in the midst of a systemic event.

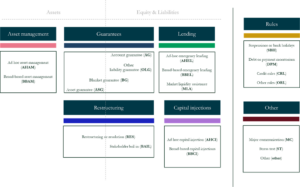

Beginning with Bagehot (1873), the management of banking crises has been closely related to the lender-of-last-resort function of central banks. But while this association is highly salient, it has never represented the full story. Instead, crisis-fighting finds central bankers joining fiscal authorities, deposit insurers, and other regulators while using multi-pronged interventions that target every region of banks’ balance sheets. In this paper, we attempt to place the March 2023 interventions within this “full balance sheet” framing, following the taxonomy and database of Metrick and Schmelzing (2023, henceforth MS – online database). Figure 1 illustrates this taxonomy with 7 major categories and 20 sub-categories; the corresponding database includes almost 2,000 interventions covering 138 countries over 750 years. Importantly, policy interventions are often associated with a “systemic” banking crises event – standard chronologies such as Reinhart and Rogoff (2009) use evidence of policy interventions to determine the severity of a bank-distress event: however, the MS database goes beyond such definitions and also includes hundreds of policy intervention events that are not included in these standard chronologies. This intervention prism allows drawing some implications for current dynamics, given the most recent sequence of events.

Figure 1: Overview of major intervention categories and subcategories during banking-crisis intervention episodes, based on Metrick and Schmelzing (2023).

Narrative

The FDIC moved first, on March 10, announcing that SBV was closed and placed into receivership (FDIC 2023a). Existing deposits would be transferred into a newly created vehicle, the “Deposit Insurance National Bank of Santa Clara” (DINB), with deposits guaranteed up to the statutory maximum of US$ 250,000 per account. As this intervention will ultimately restructure the whole balance sheet of the bank, it is classified as “resolution and restructuring” and spans both sides of the balance sheet at the bottom of Figure 1.

Over the subsequent weekend, the Federal Reserve announced the creation of an emergency lending facility, the “Bank Term Funding Program” (BTFP), from which all eligible depository institutions could borrow against “good collateral” (Fed 2023a). Within the major “lending” category of Figure 1, this intervention would be classified in the sub-category of “Broad-based

emergency lending” (“BBEL”), with the deployment intended to shore up the liability side of the balance sheet across a major part of the U.S. banking sector.

By Monday, to prevent a spillover of the distress at SVB into the wider banking system, public authorities expanded the protection of depositors beyond the statutory maximum set by the existing deposit insurance mechanism in the U.S., set an US$ 250,000 per depositor. As more than 90% of SVB’s deposit liabilities were concentrated in accounts above this maximum limit, the FDIC intervention guaranteed a substantial share of otherwise uninsured deposit volumes at SVB. This particular second step – announced by the FDIC on March 13 (FDIC 2023b) – can be classified as an “account guarantee” intervention in the MS classification scheme, part of the major category of “guarantee” interventions. Such account guarantees lie on the liability side of Figure 1, while other subcategories within guarantees may lie on the asset side, or straddle both sides.

German and British authorities reacted to SVB events on the international level. The German financial regulator announced on March 13 that a “moratorium” had been placed on the German subsidiary of SVB, which was incorporated under German corporate law with EUR 789M in assets (BaFin 2023). This decision falls into the “Debt and Payment moratoria” (“DPM”) sub-category in the MS taxonomy, one among four “rules” category interventions listed adjacent to the balance sheet.

Amid the fallout that started in the U.S., distress had spilled over to institutions in Europe by week two: in particular, the Swiss house of Credit Suisse (CS) experienced steep equity losses after a key investor refused to inject additional new capital. By March 15, pressure was building on the Swiss National Bank (SNB) to alleviate the situation and prevent systemic repercussions. Indeed, on the next day, the SNB released details of a liquidity intervention were released, with monetary authorities confirming that they would provide up to CHF 50BN in lending funds to the single institution (SNB 2023a). The actions by the Swiss monetary authorities also fall into the “lending” category in the MS taxonomy – but, since they contrast with the U.S. decision to offer lending to the entire deposit-taking sector, and target a single institution only, are designated as a “Ad hoc emergency lending” (“AHEL”) sub-type.

In the wake of continued equity price declines, however, it soon became clear that authorities need to go beyond the lending category. On the night of March 19, it was announced that rival UBS would be taking over CS at a heavily discounted purchase price – an event falling into the “Restructuring” (“RES”) category, with private sector involvement. Unsecured bondholders (AT1) would be wiped out – a separate decision representing a private sector bail-in (“BAIL” in the MS taxonomy) – with the Swiss government extending an asset guarantee for selected portfolio components up to CHF 9BN (“ASG”), and an additional liquidity pledge from the SNB to UBS, for up to CHF 100BN (“AHEL”), as well as an increase of the liquidity assistance for CS to CHF 100BN, via Council (2023a) and SNB (2023b).

By Thursday, March 16, a joint Treasury-Fed statement confirmed that a group of eleven private banking institutions was committed to support one of its peers, First Republic Bank (FRC), by depositing US$ 30BN in funds with the bank. As institution-specific equity losses persisted, press reports as of March 21 indicate private-sector discussions to organize a capital injection into FRC (a move that would represent an “AHCI” intervention).

Historical context and patterns: frequency, size, and combinations

The “Lending” intervention category is among the most frequently deployed category over time and space: the MS database counts a total of 540 individual lending policy interventions over the centuries, of which 410 were deployed across countries since the year 1870. Out of the total lending intervention count, 245 took the form of a “Broad-based emergency lending” (BBEL) interventions – the historical equivalents of the Fed’s “BTFP” facility announced this March – of which 206 are recorded since the year 1870 alone. Meanwhile, the SNB’s decision to deploy a targeted “AHEL” intervention in support of an individual institution also follows established patterns: in fact, “AHEL” deployments – of which MS count a total of 260 over time – are the single most frequent intervention sub-type in history: Swiss authorities alone activated specific “AHEL” programs no less than 14 times since 1838, when they decided to support the “Berne Kantonalbank” by depositing additional state funds into the institution in an “AHEL” operation.

The “guarantee” intervention type associated with the protection of SVB depositors equally stands in a long line of precedents – “account guarantees” in particular have been deployed 109 times across the international financial system since 1870 alone (another 21 times prior to this date). In fact, the earliest “account guarantee” intervention can be traced back more than 700 years: in November 1299, city authorities in the (then) financial hub of Barcelona decided to guarantee depositors in several merchant banks after the bankruptcy of a key lender, Berenguer de Finestres (Bensch 1989; MS).

In the MS database, not just public, but also a broad sample of private sector interventions (including private sector burden sharing) into other private sector institutions are covered: therefore, a total of 214 of precedents of “private-to-private” crisis interventions analogous to the present interventions into FRC and CS can be studied (an example being the Daiwa bailout of its competitor Cosmo in 1993 Japan, or the more recent capital injection into Dusseldorfer Hypo by the German Banking Association in March 2015).

How unique is the combination of account guarantee and emergency lending interventions, as deployed in March 2023? In the MS database, a total of 57 banking crises (therefore 6.5% of all crises) exhibit such a combination over time: it is therefore in fact a relatively rare occurrence to see such a particular policy mix deployed – among this crisis sample are both emerging and developed financial systems, including the crisis cases of Argentina 1980, Denmark 1907, France 1848, Indonesia 1992, Norway 1987, and Ireland 2008. The sample shrinks even further if we isolate cases with such a policy combination that in addition saw some form of private-sector involvement in the crisis intervention: only twelve banking crises – Australia 1843, Australia 1893, Denmark 1907, Greece 1931, Germany 1931, Finland 1933, Hong Kong 1965, Canada 1983, Norway 1987, Denmark 1987, Denmark 2008, and Germany 2008 – feature this exact intervention profile. Within this subsample, in only three crises does the private participation involve a bail-in: Australia 1893, Columbia 1982, and Denmark 1987.

Importantly, the dual intervention-level and crisis-level lenses in the MS database now allow a general association of banking crisis types conditional on intervention choices. Specifically, one can ask whether the relevant 57 crises with confirmed AG + AHEL/BBEL interventions were typically classified as “systemic” banking crises by subsequent reference literature. Indeed, undertaking this exercise, we find that 45 out of the 57 relevant crises are indeed labelled systemic in reference literature (with such systemic events labelled “canonical” in the MS database, and with such a classification relying on previous chronologies including Reinhart and Rogoff 2009; Schularick and Taylor 2012; Laeven and Valencia; and Baron, Verner, and Xiong 2022; meanwhile, “candidate” crises are newly identified distress episodes that are not associated with systemic events in existing chronologies). In contrast, out of the entire 880 crises sample covered in MS featuring all possible intervention combinations, only 52% (456) qualify as systemic. Therefore, the March 2023 pattern of interventions strongly suggests we are already in the midst of a systemic event.

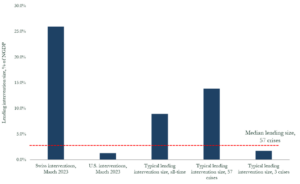

How sizable are the most recent policy intervention in long-run context? As MS also provide information of the intervention size, researchers can study the intensity of policy interventions across categories over time, extending contemporary best practice methodologies across space and time. Specifically, SVB’s uninsured deposits – those above the US$ 250,000 limit – can be estimated from regulatory filings as US$148 billion for year-end 2022, in addition to US$ 79.5BN at Signature Bank (SPG 2023). Hence, these newly announced account guarantees by the FDIC comprises 0.9% of U.S. 2022 NGDP. This compares to a median size of 2.5% of NGDP for a sample of 83 guarantee interventions over time, for which consistent size calculations can be obtained (mean: 13.1%). For the U.S. sample itself, the March 2023 guarantees mark the second-largest guarantee interventions ever, after the 2008 crisis guarantees, which amounted to more than 4% of U.S. NGDP. With uninsured deposit volumes at U.S. regional banks alone ranging in the hundreds of billions of US$, the presently contemplated extension of deposit guarantees could eventually amount to the largest guarantee operation in U.S. financial history – at the time of writing, support remains concentrated on the lending channel, with Fed data indicating an additional liquidity provision through “BTFP” and discount window operations of 1.17% of U.S. GDP as of March 23, or US$ 297BN (Reuters 2023; Fed 2023b). Similar all-time record sizes relative to output figures would apply if even a fraction of presently recognized mark-to-market asset losses are targeted via policy interventions (Jiang et al. 2023). Meanwhile, the US$ 30BN “private-to-private” lending intervention into First Republic, at 0.12% of NGDP, in itself represents a comparatively small deployment.

In contrast, the combined Swiss “AHEL” interventions, totaling CHF 200BN, stand at 25.9% of Swiss 2022 NGDP, compared to a median lending intervention size of 1.5% for a sample of 293 cases for which consistent lending size figures can be obtained (mean: 8.9%). Not least, this size for March 2023 does not significantly fall short of the total combined liquidity provisions of the Swiss National Bank for the banking sector over the one-and-a-half centuries over 1859-2010 covered in MS (at 37%), including the Swiss interventions during the Great Depression and the 2008 GFC.

Figure 2 summarizes the evidence for lending interventions, putting March 2023 interventions into context. Depending on which context one chooses, the most recent lending interventions are already far outstripping long-run precedents (Switzerland), or still falling short (U.S.) – in the case of the U.S., past patterns indicate that lending interventions may yet significantly grow in size in the present distress episode, as they remain less than half of long-run averages.

In total, the evidence suggests that recent policy interventions are building on deep structural trends, as highlighted in MS: secularly, policy interventions are becoming more sizable relative to output, and encompass a greater share of advanced economy GDP at the same time. But the particular combination of policy interventions seen as of this writing – the combination of account guarantees and emergency lending, additionally coupled with a private sector involvement – still indicates a rather unusual response pattern.

Figure 2: Overview of lending intervention sizes relative to NGDP over time, March 2023 Swiss and U.S. interventions in relation to all-time lending sizes, and most closely related subsamples (mean size to NGDP).

Conclusion

In March 2023, policymakers opted for a specific mix of interventions into the U.S. and European banking sectors – designed to support different areas of bank balance sheets in the context of a sudden bout of financial distress. A comprehensive new database documenting and classifying banking-crisis policy interventions over centuries now allows a granular contextualization of current events across a variety of operational dimensions. By combining “lending”, “guarantee”, and “restructuring” interventions, authorities expanded on a long pattern of such actions during distress episodes. But only 57 bank distress episodes over time have seen such a particular mix, and only three have witnessed them combined with relevant private-sector bail-ins. Several of the recent interventions already constitute sizable interventions in long-run context, thereby continuing a secular trend of ever greater policy interventions as measured relative to economic output: but past evidence suggests that these interventions may yet grow substantially further in size, and could reach new all-time records. Importantly, conditioning banking crises types on the policy intervention mix suggests that a substantial share of distress events over time showing the presently unfolding intervention pattern eventually assumed “systemic” crisis dimensions, an outcome associated with meaningfully higher financial and real economic costs and dislocations.

Print

Print