Albert H. Choi is the Paul G. Kauper Professor of Law, and Jeffery Y. Zhang is an Assistant Professor of Law at the University of Michigan Law School. This post is based on their paper.

In March 2023, a financial panic that began with runs on Silicon Valley Bank in California led to three of the four largest bank failures in US history. The turmoil was not contained within the United States. Jitteriness about the overall health of banks spread to Switzerland and claimed Credit Suisse as a victim. In response, the Swiss government engineered an emergency takeover of Credit Suisse by UBS to avoid economic devastation. Shareholders of Credit Suisse were given 1 UBS share for every 22.48 Credit Suisse shares as part of the emergency deal. In other words, Credit Suisse was bailed out—the antithesis of every regulatory innovation since the 2007-08 Global Financial Crisis. This government intervention wasn’t supposed to happen, especially because Credit Suisse had “CoCos” on its balance sheet prior to the panic.

What are CoCos and why do they matter? In the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis, regulators huddled together in Basel, Switzerland, to begin crafting a new financial regulatory framework. In response to the backlash against the use of public money to rescue financial institutions, their motivation was to realize an aspiration that taxpayers would no longer be left holding the bag during times of crisis. No more bailouts. This new regulatory framework contained dozens of pieces, but at its core was a unique regulatory experiment—the creation of a new debt instrument that could be converted into equity.

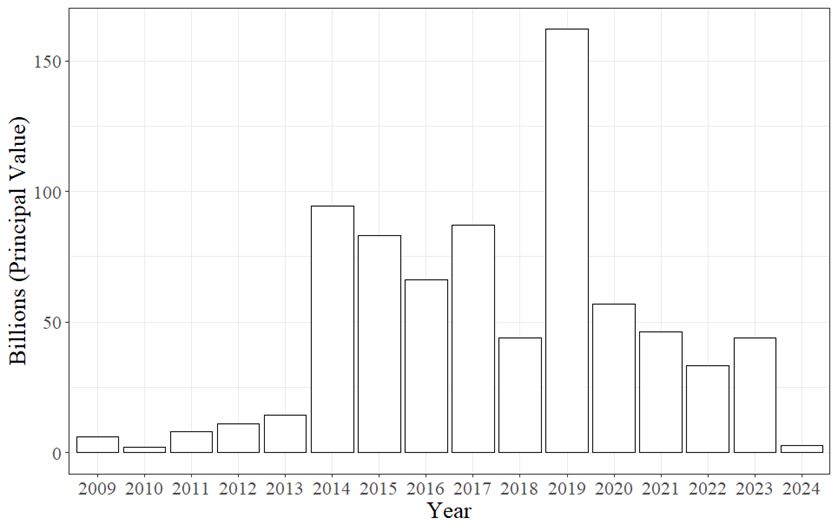

Despite their unconventional name, the underlying idea was conventional from a regulatory perspective. Banks would issue CoCos to increase their regulatory capital buffers and hold these bonds as liabilities on their balance sheets. If the banks fell into financial trouble, the CoCos would be “triggered” and either converted into equity or be written down to zero in order to reduce the banks’ liabilities. In turn, the banks would be pulled back from the brink. And the private CoCo bondholders—neither purely creditors nor purely shareholders—would be the losers holding the bag, not the public. In total, over $714 billion dollars’ worth of CoCos were issued by over 360 international banks from 2009 through the end of 2022. The figure below depicts the substantial annual issuances. Regulators had hoped that CoCos would make bank bailouts unnecessary.

Figure: Amount of CoCos Issued Since 2009

Many academic scholars had similar hopes. Within the finance and economics literature, for example, scholars have argued that CoCos could be valuable in recapitalizing banks during times of stress and could incentivize banks to improve risk management. In a recent paper, we approach the problem from a new angle using economic theory as well as three important case studies. We conclude that the regulatory experiment, in its current form, has failed and that regulators should either try to revamp it or eliminate it altogether. The status quo is untenable.

Why weren’t CoCos effective in preventing a bailout? In designing these new convertible debt instruments, regulators operated under a fundamental misunderstanding of bank runs. First, from a finance perspective, bank runs occur because of a liquidity crisis, which means the bank does not have enough liquid assets on hand to meet depositor demands for redemptions. Once a liquidity crisis is set in motion, only more liquidity can prevent the bank’s complete failure. Increasing the equity on a bank’s balance sheet, which is what CoCos are designed to do, will not improve the bank’s liquidity position, and will not stop the run. Second, we highlight the importance of information opacity during a panic. If investors and depositors are able to identify which bank is experiencing financial trouble or the magnitude of that trouble, the identified bank becomes more likely to fail. Hiding the identity of the bank or the magnitude of its trouble from the public becomes paramount. In that light, triggering CoCos ironically signals to investors and depositors that the bank is in (desperate) need of help. In other words, a CoCo conversion could precipitate the very death spiral it seeks to avoid.

With our theoretical framework in place, the paper explains why CoCos are flawed by design. The paper starts with a brief overview of the experiment that regulators implemented after the Global Financial Crisis. Regulators believed that the following sequence of events would occur by triggering the bonds’ conversion: (a) the bank would immediately have more equity and less liabilities on its balance sheet, thereby making the bank more robust, (b) depositors and market actors would see the increased equity and the improved financial position, and (c) the panic would subside. But, as shown by our framework and past experience, the combination of (a) and (b) does not imply (c). While depositors care about equity on the bank’s balance sheet during normal times, they do not care about equity during a panic; they simply want cash to meet their withdrawal requests because they know the bank does not have enough cash on hand to make every depositor whole. Second, triggering convertible bonds makes the public even more suspicious of the bank because it sends an adverse signal. It’s stigmatizing, and the panic worsens.

Large international banks still have hundreds of billions’ worth of CoCos on their books, and over $32 billion in new CoCos have been issued since the collapse of Credit Suisse. In the last part of the paper, we leverage our insights to examine if this regulatory experiment is salvageable. We believe there are certain design choices that can be altered to make CoCos more effective in preventing bank runs. Foremost, the conversion should happen early—well before a liquidity crisis has emerged. Once a run is underway, triggering the bond conversions will not stop the run. Second, we argue that the trigger mechanism should be designed in such a way to send as little information as possible to the market and depositors. This includes greater reliance on regulators’ discretion—as opposed to a trigger mechanism that is based on publicly available market indicators—and possibly a simultaneous conversion across several banks so as to prevent the market from identifying which specific bank(s) may be in trouble. The paper also compares different types of conversions and elaborates upon legal and policy hurdles to our proposed reform.

To be clear, we do not suggest that policymakers must fix the CoCos regime, because there are significant obstacles that are associated with the proposed solution. If policymakers decide that our proposed changes are too difficult to implement, they should end the regulatory experiment altogether. This version of the regulatory experiment has failed.

The full paper is available here.

Print

Print