Keith Halverstam, Maj Vaseghi, and Jenna Cooper are Partners at Latham & Watkins LLP. This post is based on a Latham memorandum by Mr. Halverstam, Ms. Vaseghi, Ms. Cooper, Joel Trotter, Holly Bauer, and Colleen Smith. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Rationalizing the Dodd-Frank Clawback (discussed on the Forum here) by Jesse Fried.

TheFAQsofferpracticaladviceforlistedcompaniesimplementingcompliantpolicies.

KeyPoints:

- By December 1, 2023, all companies listed on the NYSE or Nasdaq must adopt clawback policies that comply with listing standards mandated by the SEC (the SEC Clawback Rules).

- ThisrequirementtoadoptnewcompliantclawbackpoliciesappliestoallUS-listedcompanies, including listed foreign private issuers (FPIs).

Adopting a Clawback Policy

1. When will companies need to publicly disclose their policies?

Companies must file their policy as an exhibit to their first annual report filed on or after December 1, 2023 (Form 10-K for US domestic issuers, Form 20-F for FPIs, Form 40-F for filers under the multijurisdictional disclosure system (MJDS), and Form N-CSR for registered management investment companies).

The SEC Staff has clarified that companies need not provide checkbox and other clawback-related disclosure “until they are required to have a recovery policy under the applicable listing standard” — that is, December 1, 2023, even though the rules and forms already include checkboxes and other disclosure requirements. See Compliance and Disclosure Interpretation (C&DI) 121H.01 (emphasis added).

We believe the guidance in C&DI 121H.01 resolves any ambiguity potentially arising under the SEC releases approving the Nasdaq and NYSE listing standards, in which the SEC provided that listed issuers must provide “the required disclosures in the applicable Commission filings on or after the effective date of October 2, 2023” (emphasis added). In particular, C&DI 121H.01 clarifies that compliance with the required disclosures, including the exhibit filing, is not expected until December 1, 2023, when the recovery policy becomes mandatory under the listing standards.

2. Does adopting the policy trigger a Form 8-K?

No. Adopting the policy does not trigger a Form 8-K, nor are companies required to post their policy on their website.

3. What happens if a company fails to adopt a compliant policy by the deadline?

While unlikely, companies may be subject to potential delisting if they do not adopt a policy by the deadline.

If Nasdaq determines that a compliance failure has occurred (including a failure to adopt a policy by the deadline), it will immediately notify the company. Within four business days of receipt of the notification, the company must issue a press release disclosing the failure. The company must also submit to Nasdaq a plan for regaining compliance within 45 days. Nasdaq can then provide the company an extension of up to 180 days to cure the deficiency. If the company does not cure the failure within the cure period provided by Nasdaq (including any extension), Nasdaq will issue a delisting letter.

NYSE-listed companies are obligated to notify the NYSE within five days of any failure to comply with the SEC Clawback Rules (including a failure to adopt a policy by the deadline). If the NYSE determines that a failure has occurred, it will promptly notify the company. Within five days of receipt of the notification, the company must contact the NYSE to discuss the status of the delinquency and issue a press release disclosing the delinquency. The NYSE may provide the company with an initial six-month cure period. If the company does not cure the failure during the initial cure period, the NYSE may grant up to an additional six-month cure period before commencing delisting procedures. Notwithstanding the foregoing, the NYSE may commence suspension and delisting procedures without affording any cure period at all based on an analysis of all relevant factors.

No later than December 31, 2023, NYSE-listed companies are also required to confirm via Listing Manager their compliance with the SEC Clawback Rules.

4. If a company adopts its policy after the deadline but before its Form 10-K filing (or Form 20-F or Form 40-F, in the case of FPIs and MJDS filers), will the NYSE and Nasdaq really begin delisting procedures, given that the compliance failure will have been cured?

Both the NYSE and Nasdaq have traditionally been receptive to companies’ response letters in delisting situations, so we expect that companies will be given the opportunity to explain the delay. But even if companies are permitted to cure the adoption failure (or granted quick relief for having cured it by the time the failure is public), the failure will be public because the company will be required to file a Form 8-K if it becomes aware of any material noncompliance with a listing standard or is notified by the applicable exchange. This public disclosure could cause negative pressure on the company’s stock as a result.

Neither the NYSE nor Nasdaq has expressly stated that the noncompliance discussed above would trigger the filing of a Form 6-K, but FPIs will still need to issue a press release in accordance with the NYSE and Nasdaq listing rules.

5. Why are some companies choosing to maintain their existing clawback policies while also adopting a new separate policy in response to the SEC Clawback Rules? In that case, does the company need to file only the new policy that addresses the SEC Clawback Rules?

Many companies have existing compensation recovery policies that are broader in scope than the SEC Clawback Rules. For example, an existing policy may (i) apply to a larger group of employees beyond current and former executive officers; (ii) allow for the clawback of compensation beyond the portion of incentive-based compensation that was erroneously received; and/or (iii) include recoupment triggers that go beyond an accounting restatement, such as misconduct causing reputational harm or breach of restrictive covenants. Compensation committees will need to decide whether to retain the broader aspects of their existing policies — a decision that will be informed by the reasons and facts surrounding the adoption of the original policies and whether those continue to be applicable.

From a governance perspective and in order to be responsive to institutional investors and advisory firms, many companies are choosing to retain the broader aspects of their existing clawback policies, either by retaining their existing policies as a separate policy or by integrating these broader aspects and the SEC Clawback Rules into one policy. With either approach, companies should retain any discretion afforded to the board of directors and administrators in respect of any retained aspect of an existing policy that goes beyond the SEC Clawback Rules.

Companies that retain their existing policies as a separate policy will only need to file the policy that is compliant with the SEC Clawback Rules.

6. Are there changes that can be made to existing compensation programs or other actions that can be taken to improve the enforceability of clawback policies? Should companies amend officer employment contracts to require compliance with new clawback policies, including for officers who later leave the company?

In response to a recent federal court case challenging the enforceability of clawback policies (in this case, prior to the stock exchange rules mandating clawbacks), some companies are requiring that executive officers sign acknowledgments agreeing to comply with the terms of those policies and to the recovery of compensation in accordance with the terms of the policies, notwithstanding any other contractual obligation to the contrary. The acknowledgments provide the company with a contractual basis to enforce the policy. Similar language can also be included in go-forward compensation arrangements, including employment agreements, cash incentive plans, equity incentive plans, and award agreements, as well as in severance agreements for departing executives.

However, acknowledgments from covered officers are not required by the SEC Clawback Rules. Companies should consult outside counsel in making this decision, as boards exercising their business judgment can make reasonable determinations for or against requiring such acknowledgments.

7. Which governance body of the company should administer the policy?

The SEC Clawback Rules require that a committee composed of independent directors charged with oversight of executive compensation, or the independent members of the board of directors, must make any determination that the recovery of erroneously awarded compensation would be impracticable. Otherwise, the SEC Clawback Rules do not explicitly prescribe which governing body of the company must administer other aspects of the clawback policy. In practice, we expect that most companies will administer their clawback policies through the compensation committees of their boards. We recommend that issuers add to their compensation committee charters (if not already included) the responsibility for overseeing and administering the clawback policy.

Enforcing a Clawback Policy

8. What types of restatements trigger a recovery under the rules? What is a “little r” restatement? What is an out-of-period adjustment?

Rule 10D-1 requires the clawback of erroneously awarded incentive-based compensation received by executive officers after an accounting restatement.

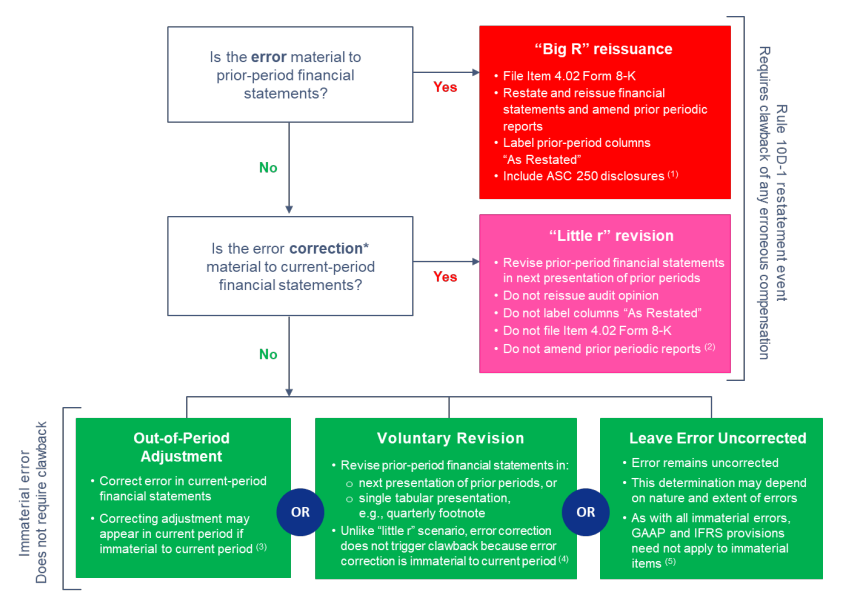

The rule includes a novel definition of an accounting restatement. The new definition’s unprecedented breadth captures not only the traditional understanding of an ASC 250 restatement “to correct an error in previously issued financial statements that is material to the previously issued financial statements” (i.e., a “Big R” restatement), but also a type of immaterial error correction process for an unreported error “that would result in a material misstatement if the error were corrected in the current period or left uncorrected in the current period” (i.e., a “little r” restatement).

The distinction between the “Big R” and “little r” scenarios hinges on whether an error identified in prior-period financial statements is material. If so, the company must correct the prior-period material error via “Big R” restatement and then determine whether executive officers received erroneously awarded compensation requiring clawback.

If the error identified in prior-period financial statements is not material, the company must evaluate whether the error correction is material to the current period. That question focuses on whether correcting the prior-period error in the current period (or leaving the error uncorrected) would materially misstate the current-period financial statements:

- If so, the company must revise the prior-period financial statements to correct the immaterial error via a “little r” restatement and then, as with a “Big R” restatement, determine whether executive officers received erroneously awarded compensation requiring clawback.

- If not, the company may correct the error in the current period through an immaterial error correction process. An out-of-period adjustment is the preferred method of correcting an immaterial error. In some cases, depending on the circumstances, the company may instead use a voluntary revision or even leave the immaterial error uncorrected. In each of these three scenarios, the company need not undertake a clawback analysis.

The flowchart on the following page summarizes each of these steps.

∗ Under Rule 10D-1(b)(1), the question is whether correcting the prior-period error in the current period (or leaving the error uncorrected) would materially misstate the current-period financial statements.

(1) ASC 250-10-50-7 requires, for the correction of a material error in previously issued financial statements: “When financial statements are restated to correct an error, the entity shall disclose that its previously issued financial statements have been restated, along with a description of the nature of the error. . . . The effect of the correction on each financial statement line item and any per-share amounts affected for each prior period presented. . . . The cumulative effect of the change on retained earnings or other appropriate components of equity or net assets in the statement of financial position, as of the beginning of the earliest period presented.” Reissued financial statements in a “Big R” restatement must be labeled “Restated” — hence the “Big R” — whereas revised financial statements in a “little r” restatement should not bear the “Big R” label.

(2) Revised financial statements are not labeled “Restated.” Optional narrative disclosure may accompany the error corrections. The financial statement audit opinion is not reissued, although the identification of a material weakness in internal control over financial reporting (ICFR) could require reissuance of the ICFR audit opinion. Form 10-K now includes two Rule 10D-1 checkboxes, an error-correction checkbox, and a clawback-analysis checkbox: (i) a company must check the first, error-correction checkbox if the financial statements in the filing include any error correction, irrespective of materiality, relating to previously issued financial statements; and (ii) a company must check the second, clawback-analysis checkbox only if the filing includes an error correction resulting from a restatement as specifically defined in Rule 10D-1 (i.e., a “Big R” restatement or a “little r” restatement) because, absent the checkbox, a reader would have no way to distinguish a “little r” restatement from a voluntary revision.

(3) The out-of-period adjustment is the most common approach for immaterial error corrections. The correcting adjustment may appear in the current period only if the adjustment is deemed immaterial to the current period financial statements.

(4) Voluntary revisions are most commonly used to correct balance sheet or cash flow errors but otherwise are often avoided to minimize potential confusion with “little r” restatements.

(5) See ASC 105-10-05-6 (“The provisions of the [Accounting Standards] Codification need not be applied to immaterial items.”); see also IAS 8, 8 (noting that IFRS policies “need not be applied when the effect of applying them is immaterial”). These principles supply the basis for leaving immaterial errors uncorrected and also apply to each of the other types of error correction approaches. However, companies can reduce the risk of both “Big R” and “little r” restatements by correcting all known errors, including immaterial errors, during the period in which the error is first identified.

9. Who determines whether an accounting error requires a restatement?

The identification and evaluation of financial statement errors requires careful analysis by management and outside auditors, and the oversight of the audit committee of the board of directors. Whether a restatement will be required depends on an evaluation of the materiality of errors in prior periods and the materiality of the possible correction of those errors in the current period. As described above, where prior-period errors are material, that requires a “Big R” restatement. Where prior-period errors are immaterial but a correcting adjustment in the current period would result in a material misstatement of the current period, that requires a “little r” restatement, in which the immaterial errors occurring in prior periods are corrected to avoid a material misstatement in the current period. These materiality determinations are often complex and require substantial time and effort by management and outside auditors, all with the oversight and ultimate review and conclusion by the audit committee of the board of directors. This determination should be informed by relevant facts and circumstances and requires a detailed materiality analysis using applicable guidance, including Staff Accounting Bulletin No. 99 and Staff Accounting Bulletin No. 108.

10. Will procedures with respect to errors that are identified in financial statements and related materiality analysis change in the face of the new clawback rules?

The playbook for assessing and correcting accounting errors will now change. Until now, the key distinction has been between “Big R” restatements versus other types of error corrections, since “Big R” restatements trigger the filing of an Item 4.02 Form 8-K (in the case of a US domestic registrant) to disclose that previously issued financial statements should no longer be relied upon and require correction via amendment to prior periodic reports. Now, “little r” restatements can also have a significant impact on an issuer by reason of application of the SEC Clawback Rules, even if prior period financial statements contain no material errors and therefore may continue to be relied upon.

The SEC’s release provides that:

“The involvement of an independent auditor in evaluating management’s materiality analyses, with the oversight of the audit committee, protects investor interests by helping ensure that material errors do not go uncorrected by an issuer seeking to avoid the recovery of erroneously awarded compensation. Furthermore, we note the potential serious consequences, including but not limited to Commission enforcement action and private litigation, of mischaracterizing material accounting errors as immaterial.”

For these reasons, the SEC did not adopt a requirement for a company to disclose the materiality analysis of an error if the company determines the error is immaterial.

The nature of a no-fault clawback policy triggered only by accounting restatements puts increased pressure on directors and employees who are responsible for reviewing financial statements and the materiality of any errors. As a result, companies are reassessing their financial reporting function to ensure that they are appropriately investing in sufficient personnel with the necessary expertise in GAAP or IFRS requirements and robust internal control over financial reporting, which is every company’s first line of defense in avoiding financial statement errors.

11. What steps should a company take once it determines that a restatement is required?

Once a company has determined that a restatement is required, it should assess whether any of its current or former executive officers’ compensation is subject to recovery.

A company should:

- Determine whether any incentive compensation was earned or vested based wholly or in part on a financial reporting measure that is restated as a result of the restatement or stock price or total shareholder return (TSR) metrics. Remember that the recovery analysis must also evaluate derivative forms of incentive compensation, including other payments that were calculated based on such incentive compensation.

- Determine if any current or former “executive officers” (as defined under Rule 10D-1) “received” the incentive compensation on or after October 2, 2023, and during the three completed fiscal years prior to the date the restatement determination is made. For purposes of this determination, compensation is received when the applicable financial reporting measure is attained.

- Confirm which current or former executive officers (1) received the incentive compensation after beginning service as executive officers, and (2) were executive officers during at least a portion of the applicable performance period.

-

- For example, if an individual is an executive officer during the beginning of the performance period for performance stock units (PSUs) tied to a financial reporting measure, but then transitions to a non-executive officer role before the PSUs are earned, the PSUs earned by this individual could be recoverable under the clawback policy, even if the individual did not serve as an executive officer either (1) at the time the PSUs were received or (2) when the company determines that a restatement is required. On the other hand, if an individual is not an executive officer during any part of the performance period for the PSUs, but transitions to an executive officer role prior to the date the company determines a restatement is required, the individual’s incentive compensation would not be subject to recovery because the individual did not serve as an executive officer during any part of the performance period.

- Determine what portion of the incentive compensation was “erroneously awarded” or, in other words, was in excess of the amount of compensation that would have been earned based on the restated financial measure. Companies may use “reasonable estimates” when determining the impact of a restatement on incentive compensation based on stock price and TSR results, as further discussed in Question 12 below.

- Assess whether the recovery of the excess compensation would be “impracticable” (e.g., the direct costs paid to third parties to enforce recovery would exceed the excess compensation after reasonable attempts, or the recovery would violate home-country law or jeopardize the qualified status of a tax-qualified retirement plan, as further discussed in Question 15 below).

- If recovery is not “impracticable,” the company is required to recover, reasonably promptly, the excess compensation on a pre-tax basis, as further discussed in Questions 14, 16, 17, and 18 below.

Once a company determines that erroneously awarded compensation has been received by a covered executive officer and an impracticability exception does not apply, it should engage in discussions with the applicable governing body and counsel regarding the desired means of recovery, necessary disclosure obligations, and communications with the applicable executive officer.

12. How should companies measure an accounting restatement’s impact on TSR and stock price metrics?

Generally, when a restatement is required and it impacts a financial reporting measure upon which incentive compensation was granted, earned, or paid, the amount of erroneously awarded compensation is subject to mathematical recalculation directly from the information in an accounting restatement. However, for incentive-based compensation earned based on TSR or stock price, the SEC recognized that direct mathematical recalculation is likely not possible. The SEC further acknowledged that the calculations necessary to determine excess compensation based on stock price and TSR may require complex analyses, significant technical expertise, and specialized knowledge. The SEC, therefore, requires companies to use “reasonable estimates” when determining the impact of a restatement on incentive-based compensation based on stock price and TSR results. Companies are also required to disclose such reasonable estimates, as discussed further below, maintain documentation of the determination, and provide such documentation to the applicable stock exchange.

For example, a company may grant performance stock units that vest in tranches based on increases in the issuer’s stock price (i.e., stock price milestones) over a 10-year period. If the company determines it must restate its financial statements for one of the years within the 10-year performance period, it should consider whether and how such restated financial statements may have impacted the issuer’s stock price such that the officer received erroneously awarded compensation based on any earned tranches achieved during the three completed fiscal years prior to the date the restatement determination is made.

Companies are advised to work with in-house and outside counsel when evaluating whether and the extent to which a restated financial metric impacted the company’s stock price or TSR performance and to take appropriate steps to document these analyses. Companies may also want to monitor peer group members’ disclosures and recoveries in connection with any clawbacks based on stock price or TSR.

13. What are the required disclosure obligations when a clawback is triggered?

If a company is required to issue an accounting restatement that triggers a clawback of erroneously awarded incentive-based compensation, it must comply with two new disclosure requirements under Item 402 of Regulation S-K (and analogous disclosure provisions in the forms applicable to FPIs and MJDS in Forms 20-F and 40-F).

First, as part of the executive compensation disclosure provisions in new Item 402(w) of Regulation S-K, if at any time during or after the last completed fiscal year the company was required to prepare an accounting restatement that required recovery pursuant to the clawback policy, or there was an outstanding balance as of the end of the last completed fiscal year of erroneously awarded compensation to be recovered from the application of the policy to a prior restatement, the company must provide in its proxy statement (and Part III of its annual report on Form 10-K):

- the date on which the company was required to prepare an accounting restatement and the aggregate dollar amount of erroneously awarded incentive-based compensation attributable to such accounting restatement (including an analysis of how the recoverable amount was calculated) or, if the amount has not yet been determined, an explanation of the reasons and disclosure of the amount and related disclosures in the next filing that is subject to Item 402 of Regulation S-K;

- the aggregate amount of incentive-based compensation that was erroneously awarded and that remains outstanding at the end of the last completed fiscal year;

- if the financial reporting measure related to a stock price or TSR metric, any estimates used in determining the amount and an explanation of the methodology used for such estimates;

- any outstanding amounts due from any current or former named executive officer for 180 days or more, separately identified for each named executive officer; and

- if recovery would be impracticable, for each current and former named executive officer and for all other current and former executive officers as a group, the amount of recovery forgone and a brief description of the reason the listed registrant decided in each case not to pursue recovery.

In addition, companies must disclose in the Summary Compensation Table the effect of any recovered amounts, which will be deducted from the applicable column in the table for the year in which the recovered amount was originally reported and identified in a footnote to the table.

Further, a company will be required to check appropriate boxes on its Form 10-K (and analogous form appliable to FPIs and MJDS, such as Form 20-F and Form 40-F) regarding whether financial statements included in the filing reflect the correction of an error to previously issued financial statements and whether any of those error corrections are restatements that require a recovery analysis of incentive-based compensation received by its executive officers.

14. What is the timing for recovery?

Companies must pursue recovery under the clawback policy “reasonably promptly.” Although the SEC does not define the term, it expects companies and their executive officers to balance cost and speed when determining the appropriate means of recovering excess compensation to safeguard the time value of any potentially recoverable compensation.

Nasdaq and the NYSE clarified that they will use a holistic approach to assess whether an issuer’s recovery meets the “reasonably promptly” standard by considering whether the issuer’s recovery efforts strike a balance of cost versus speed and whether such efforts are appropriate in light of the facts and circumstances surrounding the recovery.

As discussed above, under the new disclosure requirement added to Item 402 of Regulation S-K, a company must disclose any erroneously awarded compensation that remains outstanding at the end of the last completed fiscal year and any amounts that are outstanding for 180 days or more. By acting efficiently to recover excess compensation, companies will minimize their ongoing disclosure obligations.

15. What level of discretion is permitted, if any?

The final rules only include limited impracticability exceptions whereby companies may forgo recovery if:

- the direct cost of recovery to third parties, including reasonable legal expenses and consulting fees, would exceed the recoverable amounts, and the company has made and documented reasonable attempts to recover the compensation and furnishes such documentation to the applicable exchange;

- the recovery would violate home-country law that was effective prior to November 28, 2022, and only if the company obtained and provided to the applicable exchange an opinion of homecountry counsel, acceptable to the applicable exchange, establishing that recovery would result in such violation; or

- such recovery would jeopardize the qualified status of a tax-qualified retirement plan.

Any determination that recovery would be impracticable in any of the above three circumstances must be made by the issuer’s committee of independent directors that is responsible for executive compensation decisions, or if no such committee exists, the independent members of the board of directors.

In practice, companies have very limited discretion about whether to recover excess compensation, and there is no exception for de minimis amounts. In order to show that direct costs of recovery exceed the recoverable amounts, the company would still have to navigate the normal recovery process, run the calculations necessary to identify the recoverable amounts against which the enforcement costs would be measured, and ultimately attempt to enforce the clawback policy, all while monitoring and documenting the associated costs along the way to prove the recovery is a futile effort. To obtain an exemption for a home-country law violation — the second recovery exemption described above — the company must obtain an opinion of home-country counsel, and the exception is only applicable if the recovery would violate a home-country law that was effective prior to November 28, 2022. These requirements may result in companies having to enforce a clawback even in countries where the clawback would be prohibited, document those efforts, and then determine that recovery is impracticable due to costs under the first recovery exemption described above.

16. How does a company collect on a clawback? What if the executive officer has already been paid the compensation and paid tax on the compensation, or the excess compensation is in the form of shares that have already been sold? What if the officer does not have the liquid assets to return erroneously issued compensation?

The amount of incentive compensation that is subject to recovery is the amount the officer received in excess of the amount that would have been received based on the restated financial statements and is computed on a pre-tax basis. Recovery may include reduction or cancelation by the company of the excess incentive compensation, reimbursement or repayment by the officer and, to the extent permitted by law or the applicable incentive plan, an offset of the excess incentive compensation against other compensation payable by the company or an affiliate of the company to such person.

This recovery could result in a harsh outcome if an executive officer has already paid potentially 50% of the excess incentive compensation to tax authorities. As discussed in more detail below, elective or mandatory holdback or deferral policies that defer payment or settlement of incentive compensation that is potentially subject to clawback, until a date after the expiration of the potential recovery period, can help to mitigate these issues if structured in an appropriate manner. Where taxes have already been paid, Section 1341 of the Internal Revenue Code, which codifies the “claim of right” doctrine, may provide relief to an executive seeking to recoup taxes paid on compensation that is recovered under the SEC Clawback Rules. Section 1341 is designed to allow a taxpayer who receives income in one year and repays it in a later year to be in the same income tax position as having not received the income at all by receiving a tax deduction or credit for the year of recovery. Executives and their advisers will need to determine Section 1341’s application to a recovery under the SEC Clawback Rules based on the relevant facts and circumstances in each case. Finally, to the extent all or a portion of the excess incentive compensation has already been recovered pursuant to the Sarbanes Oxley Act Section 304 or otherwise, the amount already recovered may be credited to the amount required to be recovered pursuant to the SEC Clawback Rules.

17. Does a company also need to recover any gains on the sale of shares that are determined to be excess incentive compensation?

A company will have to consider whether to recover any gains on the sale of shares that are determined to be excess incentive compensation. For example, a company may grant to an executive officer PSUs that vest based on return on invested capital over a three-year performance period ending in 2026, and in 2027, the officer decides to sell the shares that were earned upon vesting of the PSUs to a third party. The company then determines in 2028 that a restatement of its 2025 financial statements is necessary and that the PSUs awarded resulted in the officer receiving erroneously awarded compensation. Given that the shares have already been sold, the company can determine whether to require reimbursement from the officer, offset the recovery against other compensation payable to the officer if permitted by applicable law (such as the officer’s bonus compensation), and/or cancel any unvested equity compensation still held by the officer (including non-incentive based compensation). If the officer sold the shares at a gain, the company must determine whether the recovery value should only take into account the proceeds from the sale based on the fair market value of the shares at the time of settlement or also take into account the value of the appreciation from the time of settlement to the date of sale. While the SEC’s proposed clawback rules issued in 2015 provided that if the excess shares have been sold, the recoverable amount would be the sale proceeds in respect to the excess number of shares, the final SEC Clawback Rules do not specifically address this treatment and do not expressly mandate the recovery of gains on the sale of shares that are excess incentive compensation. Instead the SEC’s release provides that the determination will depend on the particular facts and circumstances applicable to that company and the executive officer’s particular compensation arrangement and that companies and their boards will be in the best position to make these determinations.

18. What should a company do if a former officer contests whether a restatement was necessary and refuses to return the erroneously awarded compensation paid to the officer?

In the case of a former officer, there may not be any future compensation payable to offset the recovery against and/or any unvested equity compensation to cancel. As a result, if a company cannot come to agreement with the former officer, the company may need to pursue recovery against the former officer through a negotiated resolution or pursue litigation. The company will face delisting if it is not able to seek recovery of the erroneously awarded compensation, unless it has made a determination that recovery of the erroneously awarded compensation falls within one of the limited impracticability exceptions, including if the company can show that the direct cost of recovery to third parties, including reasonable legal expenses and consulting fees, would exceed the recoverable amounts, and the company has made and documented reasonable attempts to recover the compensation and furnishes such documentation to the applicable exchange. If recovery would be impracticable, the company will need to disclose in its proxy statement (and Part III of its annual report on Form 10-K) for each current and former named executive officer and for all other current and former executive officers as a group, the amount of recovery forgone and a brief description of the reason the company decided to not pursue recovery

19. What is the shareholder litigation risk related to a clawback policy?

A significant number of law firms specialize in representing shareholder plaintiffs in challenges to public company corporate governance matters, including executive compensation and benefits matters. These firms may identify companies that are not in compliance with the rules and pursue demands or fiduciary duty claims against boards that they believe should execute a clawback or have not implemented sufficient clawbacks. These shareholder firms may identify other ways in which the company is not compliant with the clawback policy and demand changes to bring the company into compliance, or threaten derivative claims for failure to meet the relevant standards.

The rules could also potentially increase the risk of liability arising from private shareholder litigation associated with “Big R” or “little r” restatements. This risk is particularly acute for executive compensation programs based on stock price or TSR targets. For example, the rules contemplate that companies must assess and publicly disclose the stock price inflation associated with previously misstated financial statements. Companies should therefore take particular care and include counsel when evaluating the stock price impact of a restatement, if any

Considerations to Mitigate the Impact of a Clawback Policy

20. What types of incentive-based compensation structures are outside the scope of the new clawback rules?

Non-financial reporting measures are not subject to clawback under the SEC Clawback Rules. Companies may therefore consider implementing incentive-based compensation that is less directly or not tied to financial reporting or TSR and stock price measures. For example, a company may currently sponsor a short-term incentive program with payouts tied to EBITDA (40% weight), free cash flow (30% weight), and a strategic objective based on meeting a research milestone (30% weight). Under this approach, if a covered restatement occurs, only the portion of the payouts based on achievement of the EBITDA and free cash flow objectives could be potentially recoverable (if the other criteria under the SEC Clawback Rules are satisfied), while the portion of the payouts based on the achievement of the strategic objective would not be subject to clawback under the policy. In this example, the company could consider shifting a higher weighting under the program to the research milestone to mitigate the impact of future restatements on the payouts under that program.

Similarly, incentive program designs that focus on annual performance periods, as opposed to multiyear performance periods, can also serve to limit the impact of a restatement on incentive compensation recovery obligations. For example, if a company grants PSUs in 2024 that are earned based on cumulative earnings per share (EPS) from 2024-2026, and the company determines in 2028 that it must restate its earnings reported in its 2025 financial statements, the entire amount of earned shares from the PSU award could be subject to recovery because the 2025 financial statements impact the cumulative EPS performance achievement for the entire three-year performance period. If instead the PSUs granted were subject to annual EPS achievement in each of 2024, 2025, and 2026, in this same scenario only the PSUs earned based on 2025 performance would be subject to recovery, as the remainder of the award would not have resulted in erroneously awarded compensation.

Further, the SEC Clawback Rules do not capture incentive awards that are granted without regard to achieving financial reporting measures, or if the vesting is solely based on continued service over time, as well as awards that are completely discretionary. While shifting some compensation to solely service-vesting compensation may be possible, significant shifts away from performance-based compensation to discretionary or solely service-vesting compensation will be viewed as a poor pay practice by institutional investors and advisory firms.

21. Should companies consider permitting executive officers to defer a portion of incentive compensation?

Due to the requirement to recover compensation on a pre-tax basis, companies may choose to implement deferral arrangements that give executive officers the election to defer payment of incentive-based compensation that is potentially subject to clawback until a date after the expiration of the recovery period. If properly structured, these types of delayed payments can potentially allow for a potential future clawback to draw from deferred amounts that have not yet been paid or subject to income tax, which may facilitate recoupment efforts because recovery is required on a pre-tax basis. Any deferral arrangements will need to be carefully reviewed in light of Section 409A of the Internal Revenue Code.

22. Can companies buy insurance or otherwise indemnify officers against the impact of the SEC Clawback Rules? How do the rules interact with indemnification agreements and bylaw provisions?

Companies are not permitted to indemnify or insure any person against losses under the SEC Clawback Rules, nor are they permitted to directly or indirectly pay or reimburse any person for any premiums for third-party insurance policies that such person may elect to purchase to fund such person’s potential obligations under the SEC Clawback Rules.

Companies’ organizational documents and indemnification agreements may include existing indemnification provisions that may appear to conflict with the SEC Clawback Rules. As part of the acknowledgement to the clawback policies, covered officers may be asked to acknowledge that they are not entitled to indemnification to the extent required by the SEC Clawback Rules.

Notably, the SEC Clawback Rules do not prohibit the right to advancement of expenses. Thus, an executive could still receive advancement for defense costs incurred in disputing a clawback if the company’s organizational documents or indemnification agreements so provide. Without such right to advancement of expenses, an executive would need to go out-of-pocket to fight a potentially improper clawback action.

Other Considerations for Foreign Private Issuers

23. How should FPIs make their officer determinations?

The SEC has modeled the definition of “executive officer” under Rule 10D-1 on the definition of “officer” under Section 16 of the Exchange Act, which is the same definition as the Exchange Act definition of executive officer but also captures the principal accounting officer (or if there is no such accounting officer, the controller). Thus, the definition includes the issuer’s president, principal financial officer, and principal accounting officer (or if there is no such accounting officer, the controller), any vice president of the issuer in charge of a principal business unit, division, or function (such as sales, administration, or finance), any other officer who performs a policy-making function, or any other person who performs similar policy-making functions for the issuer.

FPIs, which are not subject to Section 16 of the Exchange Act, will need to determine which of their senior management are executive officers subject to the new clawback rules. We recommend that a company make the determination at the time the policy is first adopted and when a new executive officer commences employment or is promoted so that the officer can be put on notice and acknowledge the policy. FPIs may also choose to have their board or other governing bodies annually confirm the list of executive officers.

In selecting executive officers, we recommend that FPIs not designate a list that is more expansive than required by the rules, as it will have collateral impacts, including subjecting the officers to longer cooling off periods under the Rule 10b5-1 plan rules and additional disclosures related to company repurchases. The company’s annual report on Form 20-F can still have a list of senior management that is different from the executive officer list.

24. How should FPIs address potential conflicts between the SEC Clawback Rules and obligations under the laws of their country of incorporation or laws of other jurisdictions where an executive may be domiciled?

In the final rule release, the SEC stated that while it recognizes some commenters’ concerns that the SEC Clawback Rules could intrude into the public policy determinations of other nations or create a disincentive for foreign firms to list in the US, issuers that choose to list on US exchanges have chosen to be subject to the rules of those exchanges and the laws of the United States.

Thus, to the extent that recovery under the SEC Clawback Rules is inconsistent with a foreign regulatory regime, the SEC Clawback Rules provide FPIs with two limited impracticability exceptions whereby they may forgo recovery if:

- the direct cost of recovery to third parties, including reasonable legal expenses and consulting fees, would exceed the recoverable amounts, and the company has made and documented reasonable attempts to recover the compensation and furnishes such documentation to the applicable exchange; or

- the recovery would violate home-country law that was effective prior to November 28, 2022, and only if the company obtained and provided to the applicable exchange an opinion of homecountry counsel, acceptable to the applicable exchange, establishing that recovery would result in such violation.

The final rule release states that the home-country law exception is limited to those laws in effect as of November 28, 2022, in order to minimize any incentive countries may have to change their laws in response to the SEC Clawback Rules. With respect to laws of jurisdictions outside of the issuer’s home country (such as the jurisdiction of the issuer’s corporate headquarters or the executive officer’s residence), the final rule release provides that to the extent the laws of these other jurisdictions would present obstacles to recovery, those obstacles need to be addressed by the discretion to not pursue recovery in situations in which the direct costs of recovering the erroneously awarded compensation would exceed the amount to be recovered.

Print

Print