Michael Ohlrogge is Associate Professor at NYU School of Law. This post is based on his recent paper.

I. Introduction

The recent failures of Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic have drawn attention to how rare it is for uninsured depositors at a failed bank to bear losses. Over the past 15 years, uninsured depositors have experienced losses in only 6% of US bank failures. In a newly released paper, I show that ubiquitous rescues of uninsured depositors represent a recent phenomenon dating only to 2008: for many years prior to that, uninsured depositor losses were the norm. I also show that the rise of uninsured depositor rescues has coincided with a dramatic increase in FDIC costs of resolving failed banks, which I estimate resulted in at least $45 billion in additional resolution expenses over the past 15 years.

The growth of uninsured depositor rescues raises serious concerns about moral hazard as well as fiscal costs. This growth also risks violating the FDIC’s statutory requirement to use the least-cost resolution method to protect insured depositors. In this paper, I present evidence that the best explanation for the growth of uninsured depositor rescues is that the FDIC has experienced “mission creep” leading it to favor rescuing depositors far more frequently than Congress intended. I show that such mission-creep has occurred twice in the past, and that Congress has successfully intervened to stop it in 1951 and 1991.

Beyond the “mission creep” theory, I also present evidence that reductions in the FDIC’s capacity to efficiently resolve failed banks may explain some of the rise of FDIC costs and uninsured depositor rescues, but that this is likely of secondary importance. By contrast, I show that it is unlikely that the rise in uninsured depositor rescues has occurred because such rescues are the most cost-effective way to protect insured depositors. I also show it is unlikely that rescues of uninsured depositors have been motivated by a political consensus beyond the FDIC to favor always rescuing uninsured depositors.

II. The Least-Cost Resolution Requirement and the Systemic Risk Exception

Current law requires the FDIC to resolve failed banks in the least-cost method that protects insured depositors. Sometimes, rescuing uninsured depositors might be the cheapest way to protect insured depositors. For instance, doing so may preserve the franchise or reputational value of a failed bank, thus making its assets more valuable, and covering the additional expense required to pay uninsured claims. Frequently, however, uninsured depositor rescues increase the total cost of resolving a failed bank. If the FDIC believes it is necessary to rescue uninsured depositors, despite it not being least cost, then it must invoke the “Systemic Risk Exception” (SRE) to the least-cost resolution requirement. Doing this requires authorization from 2/3 of the FDIC Board, 2/3 of the Fed Board, the Secretary of the Treasury, and the US President. The FDIC has invoked this only twice for failed banks: SVB and Signature, both of which failed in 2023. Thus, the SRE is not invoked lightly.

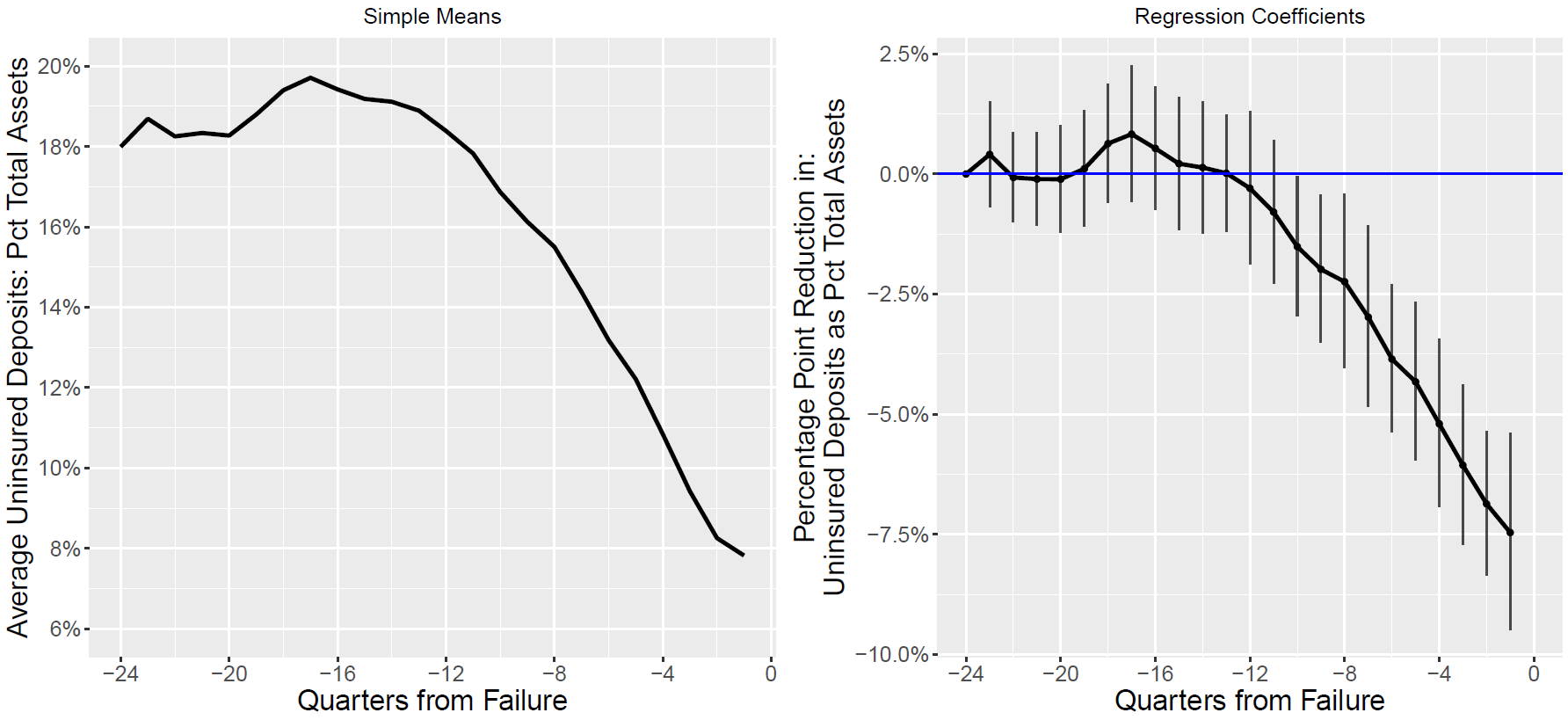

III. Reasons to Worry About Excessive Uninsured Depositor Rescues

Beyond increasing costs of resolving failed banks, excessive rescues of uninsured depositors risk reducing the incentives of uninsured depositors to monitor banks, which can encourage banks to take excessive risks. Existing research (detailed in the full paper) shows significant evidence, over many different time periods, that uninsured depositors play an active role in monitoring and disciplining banks. The data I analyze confirm these results. Figure 1 considers data from all banks that have failed over the past 30 years. Panel (a) shows that on average, starting 4 years prior to failure, the percent of bank’s total assets that are funded with uninsured depositors begins dropping, with banks losing roughly half or more of their uninsured deposits by the time they fail. Panel (b) presents similar results in a regression form. The regression shows that banks that fail lose significantly more uninsured deposits compared to banks that are similarly sized and that do not fail (this is based on including size-group-by-quarter fixed effects; similar results come from CBSA-by-quarter fixed effects). Thus, uninsured depositors appear to be aware of how safe the banks they deposit money in are, and that they flee poorly run banks. This of course does not guarantee that banks will always be prudently run. Nevertheless, it creates disincentives for banks to pursue unsafe strategies, and thus helps to promote financial stability.

Figure 1: Flight of Uninsured Depositors from Failing Banks

If uninsured depositors do not wish to monitor the safety of banks, there are other ways they can protect their funds. In particular, they can use so-called sweep accounts, that automatically move balances beyond a specified limit (such as the FDIC insurance limit) into Treasury money market mutual funds (MMFs) or similar investments at the end of each day. This enables the convenience of checking and savings accounts along with the safety of Treasury securities. Thus, imposing loses on uninsured depositors at failed banks does not mean that every person or business with more than $250,000 must necessarily put their funds at risk.

IV. Reasons to Believe the FDIC Now Favors Uninsured Depositor Rescues

Although I cannot prove it with complete certainty, I show that there are numerous reasons to believe that the FDIC has drifted from its statutory mandate to protect insured depositors a minimal cost, and has begun rescuing uninsured depositors even when doing so substantially increases resolution costs. This raises concerns about promoting moral hazard among depositors and increasing insurance costs borne by prudently run banks.

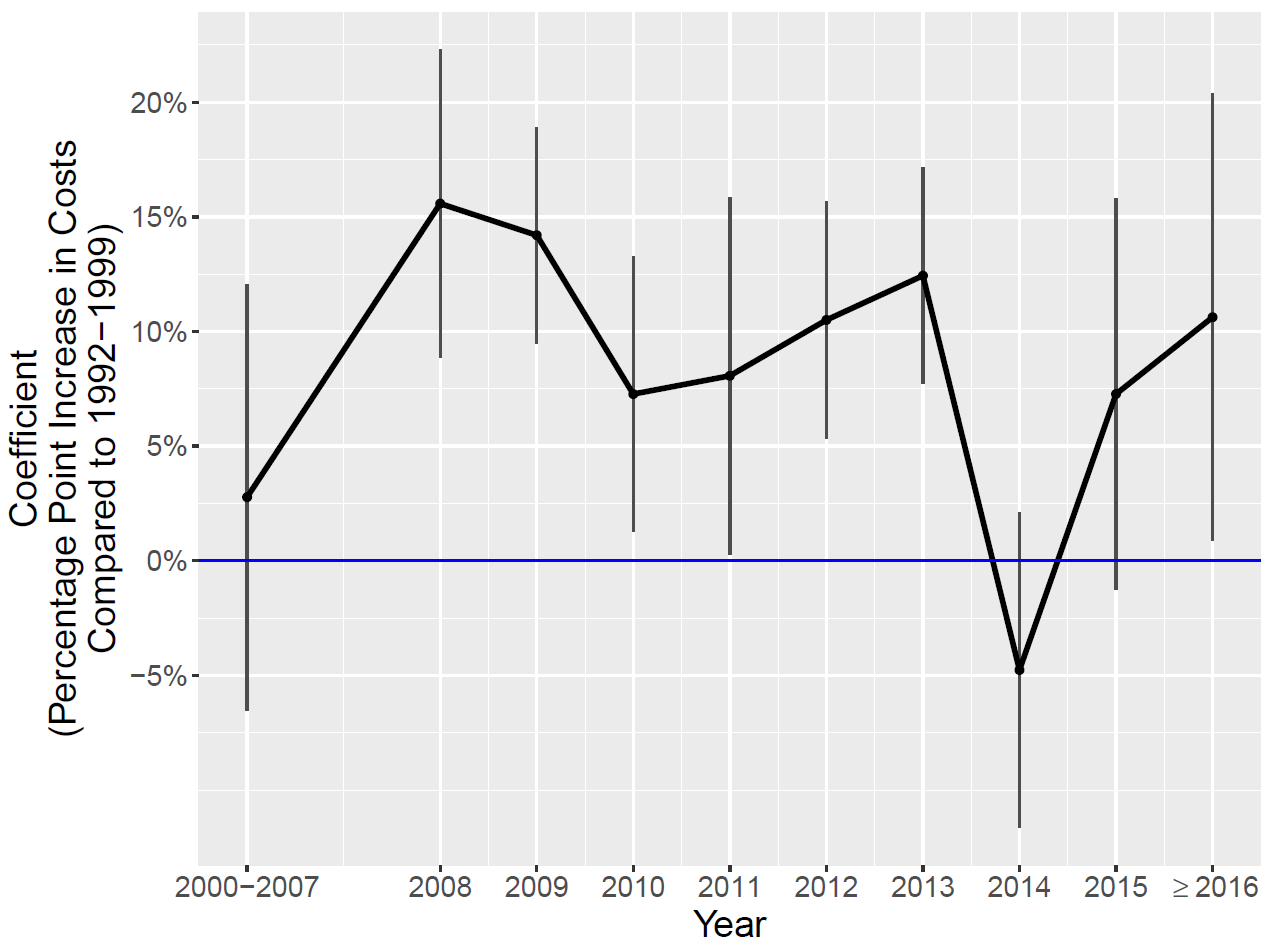

Reason #1: FDIC costs have risen dramatically at the same time uninsured depositor rescues have become ubiquitous.

- From 1992-2007, the average cost of resolving failed banks, as a percent of the failed banks’ assets, was 10%. Likewise, uninsured depositors experienced losses in 63% of bank failures.

- From 2008 onwards, by contrast, average costs of resolving failed banks have risen to 18.2% of failed banks’ assets, and uninsured depositors have experienced losses in only 6% of bank failures.

- The elevation in the FDIC’s costs persists well past the end of the 2008 financial crisis. It likewise persists in regression analyses that control for the amount of insured deposits banks have, the quality of bank assets at the time of failure, and the set of institutions available to bid on a failed bank’s assets. Figure 2 plots yearly coefficient estimates from these regressions that measure the change in FDIC resolution costs compared to costs from 1992-1999.

- While the tight correlation between rising costs and rising uninsured depositor rescues does not prove causation, there are strong theoretical reasons to believe that uninsured depositor rescues would cause costs to rise. Furthermore, neither the FDIC nor any other writers have proposed other explanations that can account for the FDIC’s dramatic rise in costs.

- I also show that the rise in costs the FDIC experienced in 2008, when it seems to have ceased following least-cost resolution requirements, is comparable to the drop in costs the FDIC experienced in 1992, when it began following the modern version of the least-cost test mandated by Congress.

Figure 2: FDIC Resolution Costs Compared to 1992-1999

Reason #2: The FDIC has twice in the past acknowledged that it adopted a preference for rescuing uninsured depositors, even when doing so increased resolution costs (I provide details of these acknowledgments in the full paper).

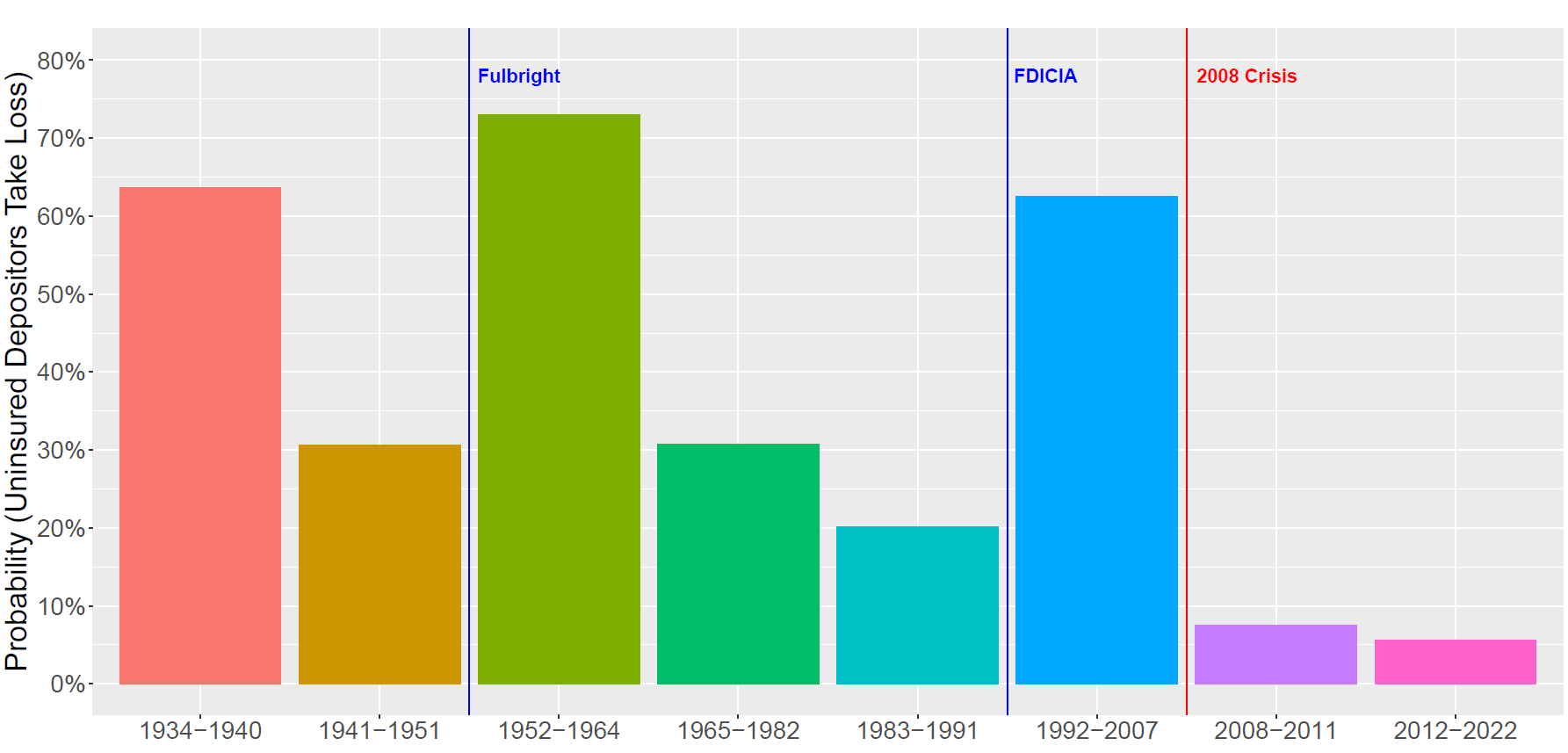

- Congress intervened in 1951 and 1991 to rein in what it viewed as excessive depositor rescues, leading to high costs and moral hazard. Figure 3 plots the frequency of losses by uninsured depositors before and after these Congressional interventions. The full paper provides more details on these interventions.

- This historical precedent shows it is plausible that the FDIC may have an institutional preference for rescuing uninsured depositors more than Congress intended.

Figure 3: Probability of Uninsured Depositor Loss, Given Bank Failure

Reason #3: Recent statements by the FDIC appear to largely acknowledge that it favors resolution methods that rescue uninsured depositors, even when doing so is not least-cost.

- For instance, the FDIC has said (see here, p.195) that starting in 2009, when it conducted auctions of a failed bank’s assets, resolutions that rescued uninsured depositors were “often the only [option] offered to potential acquirers.”

- The FDIC has also stated (see here, p.21) that it favors resolution methods that rescue uninsured depositors because they promote “financial stability,” even though Congress has been clear that if the FDIC wishes to rescue uninsured depositors on account of financial stability concerns, it must seek authorization through the Systemic Risk Exception.

Reason #4: If it were least-cost to impose losses on uninsured depositors in 63% of failures from 1992-2007, why would it now only be least-cost to impose losses in 6% of failures?

- Such a dramatic change would suggest some fundamental shift in the nature of banks or the banking industry. Yet there is no available evidence of such a shift that could explain this.

Reason #5: Mechanisms for transparency and accountability are absent or have disappeared.

- Prior to 2008, the FDIC conducted least-cost audits with some regularity, examining past failures to determine whether it had resolved the banks in the most cost-effective means. Post-2008, these audits have essentially ceased.

- The FDIC maintains strict secrecy regarding the methods it uses to compute the costs of different resolution methods, making it impossible for outsiders to verify the FDIC’s claims that rescuing uninsured depositors has now essentially always become the cheapest way to protect insured deposits.

V. Additional Considerations

In the full paper, I consider several other possible explanations for changes in the FDIC’s costs and resolution methods over the past fifteen years. Here, I briefly survey some of those considerations.

Consideration #1: Is the FDIC simply responding to broader political forces that favor rescuing uninsured depositors?

- If the FDIC’s deviations from the least-cost requirement reflect a broader political consensus favoring uninsured depositor rescues, then the potential lack of statutory adherence may seem less troubling.

- In the paper, I show that this is unlikely. The reason is that since 2008, there have been 12 failures of banks with over $1 billion in assets where uninsured depositors still took a loss. If there were a broader political consensus in favor of rescues of uninsured depositors, the FDIC could simply have asked for SRE authorization to rescue uninsured depositors in these cases.

- Instead, the decisive factor in whether uninsured depositors take losses appears to be, when conducting an auction to resolve a failed, whether the FDIC receives at least one bid for a resolution that will protect uninsured depositors. If the FDIC receives such a bid, it will almost certainly accept it, regardless of how high the costs are (for instance, the bid might agree to accept all of a failed bank’s assets and all of its liabilities, in exchange for a $1 billion payment by the FDIC to the acquiring institution). But, if the FDIC receives no such bid, it will allow uninsured depositors to experience a loss, rather than seeking SRE authorization to rescue them.

Consideration #2: Can lack of FDIC capacity help explain rising FDIC costs or depositor rescues?

- In 2008, the FDIC experienced significant staffing shortages that took until 2010 to resolve.

- It is possible that these staffing shortages led the FDIC to favor selling failed banks as a whole, a method that rescues uninsured depositors and that is simpler and easier for the FDIC to implement.

- Thus, some of the elevation of the FDIC’s costs could be attributable to staffing shortages.

- Nevertheless, as Figure 2 and Figure 3 show, elevated costs and depositor rescues persist long after these staffing shortages were resolved.

- For this and similar reasons I present in the paper, I conclude that FDIC capacity may explain a small amount of the change in FDIC costs and depositor rescues, but that it is implausible that it is a dominant driver of the dramatic changes shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

VI. Policy Reforms

One potential response to the phenomena I document is for Congress to make the de facto total deposit insurance de jure and thus to eliminate the $250,000 cap on insured deposits. In the full paper I give numerous reasons to be cautious of such an approach, but fulling assessing its merits or demerits is beyond the scope of this research. At a minimum, however, democratic accountability demands that such a change be made by Congress, not by the FDIC.

Beyond this, I propose several reforms that can improve adherence to the FDIC’s least-cost resolution requirement, and thus reduce resolution costs and moral hazard. These include:

- Require GAO audits of the FDIC’s compliance with the least-cost resolution requirement.

- When banks bid to acquire a failed bank’s assets, prohibit the FDIC from knowing whether the bidders intend to rescue uninsured depositors. Instead, if the winning bidder wishes to use their funds to rescue uninsured depositors, they can do so on their own accord. This will help ensure the FDIC selects bids that are truly least cost, rather than giving preference to bids that will rescue uninsured depositors.

- Grant insured deposits priority over uninsured deposits, matching the system in place in much of Europe. This contrasts with the status quo in the US which gives equal priority to insured and uninsured deposits. I show that this could further reduce FDIC resolution costs while improving incentives for depositor discipline.

- If the FDIC is concerned about lack of staff capacity impeding resolution efficiency, it should do more to use bridge banks that allow failed banks to operate in receivership, akin to a Chapter 11 Debtor-in-Possession for corporate bankruptcy. This makes use of the large base of staff members who are already employed by the failed banks, and who can continue to manage the assets of those banks as they did pre-failure.

Print

Print